Maybe it’s hard to believe now, but liberalism once seemed ascendant. In 2008, the nation elected Barack Obama, its first Black president, a man who ran on hope and transformative change. Millennials were secularizing and liberalizing on issues like LGBTQ+ rights. Obama passed health-care reform. Toward the end of his second term, the Supreme Court would rule in favor of marriage equality, and joyful singing crowds swallowed up the bigots who stalked the grounds with their signs and their shofars. The America I knew as a child of the Christian right was far removed from the America I had come to inhabit, or so I thought.

Threats crowded the horizon: The Obama era also marked the rise of the tea party. A year before the Supreme Court extended marriage rights in Obergefell v. Hodges, it found that corporations could refuse to cover contraception if doing so violated their religious beliefs. The year of Obergefell was the year too of Donald Trump. He announced his campaign for president in June 2015, not long before celebratory crowds thronged in front of the Court.

Back then, Trump was a longshot, an unsavory joke. That July, a CNN/Pivit analysis said he had a one percent chance of becoming president. “Donald Trump will not be the 45th president of the United States. Nor the 46th, nor any other number you might name,” James Fallows wrote the same month in The Atlantic. “The chance of his winning nomination and election is exactly zero.” This was the conventional wisdom: The national immune system would kick in, liberals and Never Trumpers said before Trump won the Republican nomination for president. They said the same thing afterward, too. The fever would break and Hillary Clinton would win.

She didn’t. Trump lost the popular vote but won the Electoral College, and his frenzied bigotry had mass appeal far beyond what the professionals expected. I had been working my first job in journalism for six weeks when he secured the presidency. That night, as silence descended over the newsroom, dread caught me by the throat. The America I’d fled in my early 20s had come for the America I’d chosen. There is a popular conviction, at least among liberals, that the Civil War is in the past and such conflicts are now unthinkable. But I had learned something different as a child. I learned that liberalism was the enemy, that the country was in danger, and that when I grew up, I’d have to take it back through politics or at gunpoint. Nobody specified which.

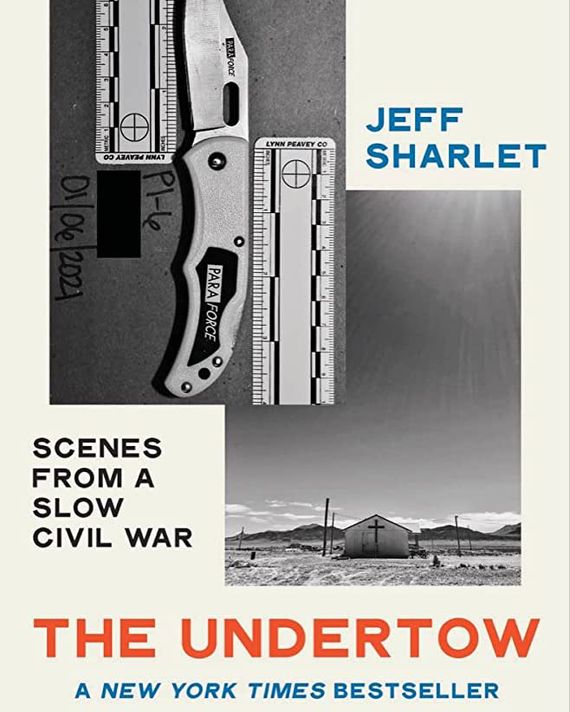

The election of Joe Biden might have slowed the rate of our disunification. What it has not done — and cannot do — is alter the existential conflict that we face. There are many Americas, and they have never been at peace with one another. That tension simmers throughout The Undertow: Scenes From A Slow Civil War, journalist Jeff Sharlet’s latest work of reportage from W.W. Norton. In his books C Street and The Family, Sharlet tracked the political influence of Christian fundamentalism. Now he encounters the foot soldiers and propagandists of an authoritarian movement that is gathering strength.

Much has been written about the figure of Trump: his biography, his appeal, his hold on the Republican Party. Some too have written about Trump’s antecedents in the broader conservative movement. But Sharlet offers something new. He follows the fever to where it burns the hottest, at the base of the Republican Party. The underlying disease is bone-deep, his reporting suggests, and the implications extend far beyond the trajectory of either political party. The triumph of multicultural democracy is in danger. At Trump rallies and church services and meetings with the devout, Sharlet uncovered a country that holds many realities at once, but perhaps not for much longer.

In the centuries since the Founders said all men were created equal, there has never been unified agreement over what this might mean, and for whom. The friction between America’s promises and its practices erupts regularly into violence: into the degradations of chattel slavery, a civil war, and the white terrorism of the Jim Crow South; then into police killings, mass shootings, and the Capitol riot of January 6, 2021. On that day, depending on your interpretation, Ashli Babbitt was either martyred or got herself killed when a police officer shot her in the act of rushing the Speaker’s Lobby. The two perspectives cannot be reconciled.

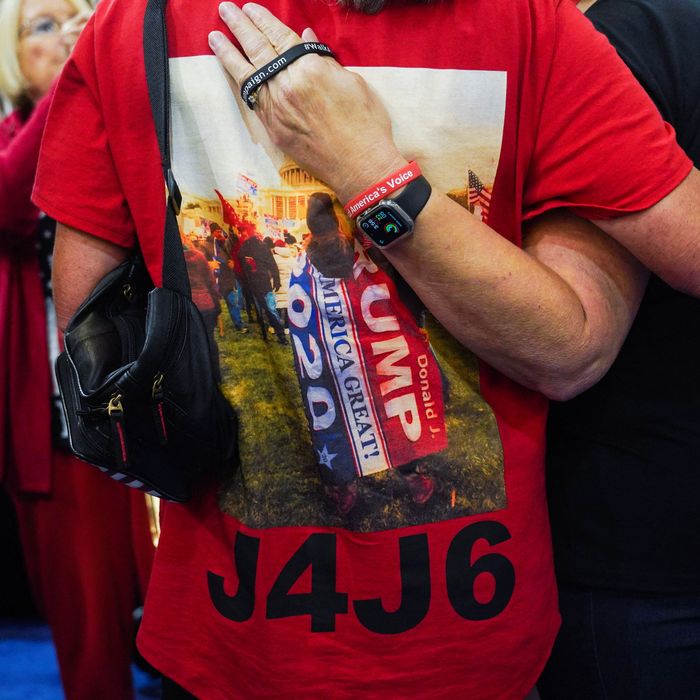

A more authentic Babbitt emerges from Sharlet’s reporting. “She was not a hashtag,” he writes. He fills in the small details of her life. Before she joined the Air Force at 17, she used to ride her horse to 7-Eleven. She voted for Obama and then, in 2016, she “fell hard for Donald J. Trump.” In death, she has become a meme. “Two words in the mouth of the man for whom she died, who did not bother to say her name for six months after that death, until the day it proved useful. To him,” Sharlet observes. Later, at a rally in Babbitt’s memory, Sharlet spots white nationalists. Fascists start a fight with anti-fascists. “What her death does, when we compare it to Crispus Attucks, is—it calls for a revolution!” a speaker says.

As Sharlet chases Babbitt’s ghost across a fractious landscape, he documents a new kind of civil war. States do not face one another on the battlefield; there is no rebel government. Instead, the battlefield is everywhere, and combatants have, in a sense, already seceded from the United States. That the secession occurred in their minds makes it no less real. They are armed, and they are backed, too, by power and money. They have successfully enthralled a major political party, and their allies are capturing courts and state legislatures. The other side is still catching up to the danger it’s in.

Some perspectives, of course, are more accurate than others. Ashli Babbitt’s America is hostile to pluralism, egalitarianism, and the very notion of democracy. The people who live there long for a strongman and believe they have found him in Trump. Sharlet knows this and contends with the implications throughout The Undertow. Sharp and probing, this book doesn’t indulge in cheap scares. Sharlet is here to inform, and The Undertow is a more powerful warning as a result.

Sharlet greets his subjects with sensitivity and brings forth their humanity, but he is uninterested in false equivalencies. When a protester interrupts a Trump speech, a man in the crowd turns to his woman and says with a smile that he would beat the shit out of him. “He stands up there and says what we all think,” the man tells Sharlet. “We all want to punch somebody in the face, and he says it for us.” Later, Sharlet observes, “Why not take pleasure in power? It feels good to be strong. It is, for the believers, whom Trump calls ‘my people,’ a blessing.”

This is fascism at work, he argues. In footnotes, he says he had once believed that “Christian nationalism’s ostensible commitment to some kind of idea of Christ prevented the movement from ever going all in on the cult of personality necessary to foment true fascism.” He has changed his mind. The movement Trump has inspired “cultivates paramilitaries,” Sharlet writes. It “glorifies violence as a means of purification, thrives on othering its enemies, declares itself persecuted for ‘Whiteness,’ diagnoses the nation as decadent, and embraces the revisionist myth of a MAGA past — as exemplified in its dream of adding Trump’s likeness to Mount Rushmore.”

In the figure of Babbitt, this new fascism sees something holy. She was “transformed” after her death, Sharlet writes, into “yet another flag, like a new tarot card in the deck of fascism,” a unifying symbol. A fringe belief, yes, but a consequential one. “The politics of the fringe may not be rational, but they’re cunning, surrounding the center and moving inward, until suddenly there they are, at the heart of things,” he writes. There is the QAnon Shaman standing in the Senate chamber, and Marjorie Taylor Greene, and Lauren Boebert, and Babbitt herself. The threat is not distant. It’s already here.

The America I once knew, which has become the land of Babbitt and Greene, always planned for expansion and conquest, not coexistence. This nation within a nation wants to triumph over all others. Trump was a means to an end, but he has become more than that, too. Like Babbitt, he is a symbol: an earthly father figure, a reflection of their God.

The Undertow is no mere guide to Trump or how he came to be, however. Sharlet’s ambitions are sweeping. The road to our present state of disunion began long ago, that much he makes clear. He writes first of the late singer and civil-rights activist Harry Belafonte, who pitted the power of his celebrity against the might of white supremacy (Klansmen chased him and Sidney Poitier one Mississippi night in 1964), as American too as the racism that would one day make Trump a power. To struggle for freedom is to live with death, Belafonte knew. He had been close to Martin Luther King Jr., then lost him to hate. “After every great victory, a great murder,” Belafonte tells Sharlet.

Surrender is not a real solution. America contains many possibilities, not all of them grim. Sharlet writes of Occupy Wall Street, which also began in the middle of the Obama era’s ascendant liberalism. A writer from Occupy Nashville tells Sharlet they are no longer operating in ordinary time but in something she calls “movement time.” “What she meant was a sort of slow motion, sped up, outside of the flow of minutes and days, the temporal experience suggested by the Christian theological term kairos, ritual time, a moment that is unique and suffused with moments past,” he theorizes. This made Occupy a kind of holiday. “There is nothing frivolous about that,” he adds. “Holidays are not escapes; at their best, they deepen our experience of things.” The Occupy movement did more than condemn inequality and attack corporate greed; it showed us all a different way of being. That is the power of movement time. It alters reality, and the consequences ripple outward where they take unexpected paths. The result can bring us closer to a future worth living.

Trump may yet be president again. His followers remain devoted, and there are enough of them to make him the early front-runner for the Republican Party nomination. His general-election chances are good but not guaranteed; his movement is a minoritarian one. Even if he loses to Biden a second time, the forces that coalesced around him could outlast his political career. How does the body of the nation come apart? Sharlet asks himself. He writes, “The answer is in the question I’d learned to ask the believers: ‘Do you think there’ll be a civil war?’ They all said ‘Yes.’ Most thought it was coming, soon, and some said it was already here.” A second Trump loss won’t quell such violent conviction.

When I left Evangelicalism over a decade ago, I did so for intellectual and moral reasons but felt, also, that I was joining a winning team. The disappointments of the Obama era radicalized me; I know now that liberalism was more fragile than it seemed. The right regrouped after Obergefell. Intent, still, on pushing LGBTQ+ people back into the closet — or eradicating them altogether — the right presses its case through so-called parental-rights candidates and anti-trans bills. At the same time, it has embraced insurrection and violence, a trend Sharlet depicts throughout The Undertow. In recent months, Trump has been promoting a single recorded by jailed January 6 defendants, and he speaks often of Babbitt as a “Great Patriot” who was murdered.

As the liberal order frays, something new must come into being. “We say we are in crisis,” Sharlet writes. “But that word, crisis, supposes we can act. It supposes the outcome is yet to be determined. The binary yet to be toggled, a happy ending or a sad one, victory or defeat. As if we have not already entered the aftermath.” If the aftermath is here, it demands an honest reckoning. A united America has never existed, and the illusion is now impossible to maintain. When one version of this nation is determined to erase another, a conflict of some kind becomes inevitable. It may well be the slow civil war of Sharlet’s title, waged by conspiracy theorists and donors and legislators, punctuated by the occasional blast of violence. But a slow civil war is still a civil war. The only recourse is to win.