This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Republic, the group that wants to abolish the British monarchy, meets in a modern church in an ugly suburb of London, as if to make a point. Two weeks before the coronation of Charles III, 70 people gather to listen to Graham Smith, the CEO of Republic, and the progressive journalist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown. They seem surprised to find news cameras there. Monarchy is sold by the British press as a blend of sacred ritual and cheap soap opera. As an institution, the crown is rarely criticized publicly. When it is, people are curious, like children who have never seen snow.

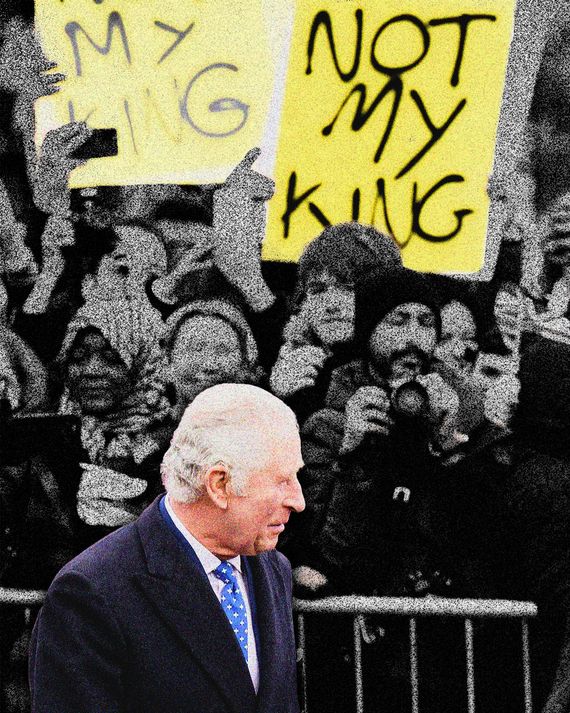

There are signs, though, that all this is starting to change. At the proclamation of King Charles in Edinburgh last September, a woman held up a sign that read, “Fuck Imperialism, Abolish Monarchy” and was promptly arrested. In Oxford, Symon Hill, a history tutor, shouted, “Who elected him?” and was charged with disorderly behavior. This is not the sort of thing a robust democracy does. The Guardian reports that the Home Office has sent letters to Republic warning the group that new rules have taken effect ahead of Charles’s coronation day on May 6 to prevent “disruption.” Protesters could face prison sentences of up to a year for blocking roads and up to six months for locking arms, and are subject to search if suspected of sowing “chaos.” Smith said the letter was “very odd.”

Republicans have long been a beleaguered minority — intellectuals, dissenters, punks, people who do not vote for the ruling Conservative Party. They can do little when monarchy is popular, and a popular monarch does two things: They plausibly mirror the country and pretend they do not want the job. Elizabeth II was all but silent — we did not know who she was — which made her a screen onto which certain ideals (stoicism, modesty, decency) could be projected. She also appeared reluctant, so we were grateful and felt sorry for her. Her approval rating upon her death was 80 percent. Charles III is not reluctant. He has fashioned two new crowns and bought two new thrones, and he will crown Camilla, the woman his first wife, Diana, hated, as queen. He mirrors only himself, since few people run Aston Martins on wine and cheese by-products and wear handmade shoes. Also, he talks a lot. The polls are duly moving away from him. Less than half of British subjects are positive about him, and 42 percent are negative. In the 16-to-24-year-old cohort, it is an abysmal 13 percent positive to 58 percent negative.

It would appear that this is the anti-monarchists’ moment. And there is a precedent. In 1649, we removed Charles I’s head. “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown,” he said, which is certainly a positive spin on entering the afterlife. It was the only English regicide not suspected to be ordered by other members of the royal family, leaving Oliver Cromwell to rule for a time until monarchy was restored in 1660. However, Republic does not endorse regicide: It wants a transition to a parliamentary democracy with an elected head of state and a written constitution. On coronation day, it will hold a demonstration in London, where its members will wear yellow.

But it isn’t clear how persuasive Republic’s arguments will be. Monarchy predates democracy by millennia, and the British love to feel exceptional — only Japan has an older crown.

At the conference, Smith is implacable in his opposition. Everything people find charming about the royals he dislikes. Every argument in their favor “is either wrong in principle, or in fact, or in both.” His argument — that the monarchy is “unaccountable and secretive,” that it “undermines our values and standards” — may seem straightforward and obvious, at least to democratic citizens who do not live under kings and queens. The royals have less accountability than the CIA. They abuse public money: “They routinely take what is ours and treat it as their own,” he says, a sentiment as old as the French Revolution.

For Alibhai-Brown, an immigrant from Uganda, monarchy is “centuries of manipulation of the peoples of this country” by a “totally dysfunctional and quite horrible family.” She met Elizabeth II three times: “I refused to curtsy.” She met Prince Philip too: “He ignored me and said to my husband, ‘Is she yours?’” She remembers a dinner with Charles, at which the playwright Harold Pinter fantasized about decapitating him. They sat near a painting of Charles I. When she reminded Pinter’s widow, the aristocratic novelist Antonia Fraser, of this, “she denied this dinner had ever happened.” Monarchy invites amnesia.

Republic wants people to remember. Alibhai-Brown reminds the attendants of royal cruelty. Elizabeth II’s sister Margaret was forbidden to marry the man she loved, she says, because he was divorced. Nerissa and Katherine, nieces of the late Queen Mother, were institutionalized due to learning disabilities, were abandoned by their family, and even reported dead in Burke’s Peerage. Broken royal bodies, as the novelist Hilary Mantel called them, are strewn everywhere, especially if female: Margaret; Diana; Meghan. The press colludes in this battery.

The Republicans may have an ideal foil in Charles, but in the future they will have to contend with his heirs. More people wanted Prince William to succeed Elizabeth II (37 percent) than Charles (34 percent), and William is plausibly reluctant — he was once described as a man looking like he punched every car door he got out of. He was also raised by police-protection officers and school masters, so he can seem normal. But he has his royal blind spots; chiding BAFTA for its lack of diversity was both absurd and very funny, since the monarchy is conservative, rich, and very white. Increasingly, Britain isn’t, and still we chased Meghan, our biracial princess, away in a self-hating bonfire of the vanities. “I think it’s a bad example for our children,” says one attendee at the Republic conference. “As a mother, I can’t imagine lifting up one child above the others,” an allusion to Prince Harry and his whistleblowing memoir, Spare. When William visited the Caribbean in 2022, he practiced empire-core, wearing white, holding hands with Black children through a wire fence, sometimes progressing in an open-top Land Rover.

But it’s not enough to complain; something must be done. In the Q&A session, the Republicans debate strategy. A man fears that Britain is immune to republicanism: “We are more conformist now than we were in the 1930s. It’s like North Korea, the Great Leader.” Some counsel waiting until the crown collapses under its contradictions. Surely there will be a sex tape eventually? Smith says that when Republican arguments are made, people are receptive, like Dorothy waking to the poppy field in Oz: “It needs to be done by us.”

The following week, the New Statesman, a left-wing magazine, hosts a debate in Cambridge, a golden university city with swans idling on the river. The proposition is: It’s time to abolish the monarchy. We count the votes before the debate; 176 would abolish the monarchy, 122 would keep it. Anna Whitelock, professor of history of monarchy at City, University of London, gets the debate going with a litany of grievances: “Criticism or debate of the royal family is prohibited in Parliament,” she notes. The royal family is exempt from the 2010 Equality Act — a fact that is both awful and apt. Charles III pays no inheritance tax and no corporation tax. The monarchy is, she says, “an institution that resists scrutiny at the apex of society which, by its very survival, reinforces hierarchy.”

Robert Hardman, a royal correspondent, represents the pro-monarchy side. He is jocular and easy; he knows the royal family and he mirrors them. His argument is: The alternative is worse. Elizabeth II, he says, “was a bucket-list head of state” protecting us “from overmighty despots. No one can get their hands on the armed forces, the honors system, the judiciary, the civil service.” When the French head of state lays a wreath, he says, “half of the people hate the person laying the wreath, and bonus points for anyone who can name more than two Italian presidents.” He concedes that the monarchy is irrational but “so is the boat race, wedding dresses, turkey at Christmas, and hot cross buns.”

He is followed by Gary Younge, a progressive journalist. “For all the talk of modernity and meritocracy,” he says, “the message from the top remains: No matter how hard you graft, sacrifice, innovate, and invest, you will never make it to those snowy white peaks which are reserved for those who were born there. It enshrines the hereditary principle in a system which increasingly enriches the privileged and privileges the rich.” Nor does it make them happy. He reminds the crowd that the Crown Prince of Nepal murdered most of his family in 2001, shot himself, inherited the crown (though in a coma — what a metaphor!), and monarchy was abolished. Younge says he would rather have a referendum than a massacre, summarizing the monarchist argument as “Save us from ourselves!”

The final vote is 202 to 77 for abolition, and the mood in the room is jubilant. But Cambridge is a city of intellectuals and the birthplace of Oliver Cromwell, as Hardman points out, acting very much like someone who has lost a battle but feels pretty confident about winning the war. Despite Republican excitement, the monarchy is sensitive to public opinion and has been unpopular before. If the crown hears Republican complaints and becomes more accountable and transparent to answer them, then that may be enough to avoid a serious reckoning. World War I felled most of the senior crowns of Europe, but not this one. It seems unlikely that any one monarch, even Charles III, can do otherwise.