This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Arthur Fletcher had already been a Baltimore Colts lineman and an administrator for the state highway department when he started applying for jobs as a football coach in Kansas. It was 1957, three years after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed de jure racial segregation in schools with Brown v. Board of Education. Fletcher lived in Topeka with his wife and five children, and he had $15,000 in debt from an ill-fated side career as a concert promoter. He was building tires for Goodyear to make ends meet, but his odds at landing a coaching job looked promising. He was, after all, the first Black player on the Colts.

But if Brown meant progress for millions of students, it meant little for Fletcher’s job prospects. “I presented myself to school board after school board after school board in the state of Kansas, and the answer was, ‘You are ready, but we’re not,’” he said, according to A Terrible Thing to Waste, historian David Hamilton Golland’s biography of him.

Fletcher never asked for special treatment. His stepfather was a buffalo soldier. Self-reliance was the gospel in his childhood home. But everywhere Fletcher looked, bigotry and discrimination were freezing Black Americans out of an equal shot at American prosperity.

Fletcher left Kansas and took his chances in the West Coast–based defense industries, while immersing himself in the world of Republican political organizing. In 1968, he ran for lieutenant governor of Washington and lost. He was nursing his wounds that autumn when the president-elect offered him a job. Richard Nixon had barely won his own race that year. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had recently been killed, and America’s streets were smoldering. Neutralizing riots was top of mind for the “law and order” candidate. The solution he chose was “Black capitalism.”

“Instead of government jobs, and government housing, and government welfare,” Nixon said at the 1968 Republican National Convention, “let government use its tax and credit policies to enlist in this battle the greatest engine of progress ever developed in the history of man — American private enterprise.” His reasoning was that government aid in Black neighborhoods created waste and dependency. To promote equality and quell unrest, Black ghetto-dwellers needed pride of ownership through entrepreneurialism — more Black businesses and Black banks in Black neighborhoods.

The pitch was a natural draw for Fletcher. If Nixon had any doubts about whether he would support his civil-rights agenda, they were swiftly put to rest. “I don’t believe in jumping to welfare when there’s so much work out there,” Fletcher said when Nixon mentioned one of his welfare initiatives.

After he took office in 1969, Nixon appointed Fletcher to be his assistant secretary of Labor, making him one of the country’s highest-ranking Black government officials. At six-foot-four with dark skin and close-cropped hair, Fletcher was a fly in Nixon’s proverbial buttermilk — an administration of slick-haired white guys known by critics as “Uncle Strom’s Cabin,” according to Mehrsa Baradaran, a UC Irvine law professor whose book The Color of Money sheds light on this era.

The policy for which Fletcher is remembered, and that earned him the nickname “the father of affirmative action,” was introduced that June. It started as a modest tweak to the federal contracting process. The construction firms and tradesmen who were winning federal contracts at the time were almost all white, a reflection of how segregated local trade unions were. “We even found Italians with green cards who couldn’t speak English, let alone read or write a word, sentence, or paragraph — yet who were working on federal contracts,” Fletcher wrote. Meanwhile, the same contractors were claiming they couldn’t find qualified Black workers, an assertion that Fletcher decided to test by forcing them to integrate. He added a provision to federal contracts that required contractors to set “goals and timetables” for hiring more Black and non-white workers, expressed as percentages that were to be increased over four years.

The Revised Philadelphia Plan, as his initiative was called, is now considered the first example of “hard” affirmative action implemented by the federal government, a term that acknowledged that merely outlawing legal discrimination was insufficient redress for the wreckage wrought by two centuries of discrimination. Proactive, or “affirmative,” measures had to be taken, too.

“I consider that my little footnote in history,” Fletcher wrote of this fateful decision. “I went into that administration with the conviction that if we could change the role of Blacks in the economy, we’d do nothing short of changing the nation’s culture.”

Not long after, Harvard Law School debuted a parallel initiative known as the Harvard Plan, the core of which was a formula for evaluating applicants that considered their racial background. That plan was later adapted for the school’s undergraduate admissions, leading to explosive growth in the share of minority admits and establishing a pattern that has since been replicated across higher education.

Fifty-four years later, that period of growth is probably ending. In October, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, two cases that, when decided in June, are expected to outlaw the consideration of race in school admissions for good and, by extension, kill affirmative action across all sectors of American life.

If all goes as anticipated, this ruling would be the latest anti-civil-rights salvo from a right-wing Supreme Court majority that has already overturned Roe v. Wade. Several turns have led us to this crossroads. The Court has played a crucial role, narrowing the scope of affirmative action to the point that its original aim — redressing the material deprivation facing Black people and other minorities — has been supplanted by anodyne gestures toward diversity. But there’s also a deeper and more familiar betrayal at work. Affirmative action emerged at a time in American history when Black civil-rights advocates were calling for a comprehensive rewrite of the social contract. The pillars of their agenda included full voting rights, equal access to education, robust anti-discrimination laws with strong enforcement, universal health care, and a full-employment economy.

In the decades since, we’ve seen those pillars falter and crumble. The Supreme Court has invited the de facto resegregation of American primary schools and gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Black communities are beset by police violence and mass incarceration. Black families are afflicted by deadly health ailments and unemployment rates that are singular on the national landscape.

Now we’re heading toward the death of America’s last surviving race-based redistributive program. The controversies surrounding affirmative action have revolved around education — in other words, the legacy of the Harvard Plan — a narrow debate that has foreclosed the possibilities of what affirmative action could have been.

Arthur Fletcher’s Philadelphia Plan is a reminder that even the less ambitious civil-rights advocates once had more expansive dreams than improving diversity in ivory towers and the C-suite. It was ultimately doomed by several overlapping factors: the GOP’s wholesale turn against Black communities, the white working class’s betrayal of their Black peers, and the government’s terror of sparking a backlash from white voters. Alongside the Harvard Plan, it represented the other half of the affirmative-action equation: the idea that the government could help build a Black middle class the same way the labor movement made a white middle class, by creating good-paying jobs for low-skilled workers without a lot of education. And it never had a chance.

The first-ever federal agency for investigating claims of racial discrimination in hiring, known as the Fair Employment Practices Committee, was created in 1941. Black workers were being denied jobs en masse despite a boom in the defense industry, and Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph threatened President Franklin D. Roosevelt with a 100,000-strong March on Washington if he did not take executive action. The FEPC managed to head off Randolph’s protest, but otherwise turned out to be functionally useless at stopping discrimination. It was defunct by 1946.

The more forceful equal-opportunity policies of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations were a response to the pressure of the civil-rights movement. Kennedy gave an executive order barring employers from discriminating on the basis of race and required federal contractors to provide equal employment opportunities — meaning not intentionally keeping non-white workers out of a job. Johnson introduced permanent contract bans for scofflaw firms, while the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which he signed into law, made discrimination across a host of categories — race, sex, religion, national origin — illegal in areas including jobs.

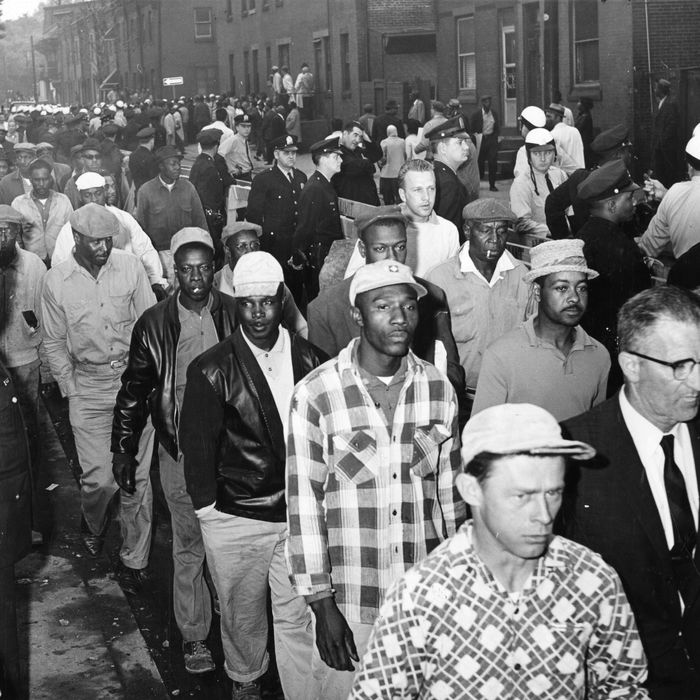

But by the time Nixon was sworn in, every major effort by the federal government to make sure employers weren’t freezing Black people out of the job market had fallen short, giving rise to the ominous possibility of Black revolt. Nixon’s first term coincided with the age of Black power, an evolution of the civil-rights movement that was more militant. Its insurrectionary edge was expressed through uprisings in the nation’s Black ghettos, and its intellectual and political sympathies were wrapped up in the revolutionary movements spanning the Global South, especially Africa. These movements were anti-imperialist, and many were Marxist. The specter of a homegrown anti-capitalist insurrection, however small, during the height of the Cold War spooked Nixon, and he responded with a deadly counterintelligence program — COINTELPRO — dedicated to neutralizing groups like the Black Panthers. Publicly, however, Nixon adopted a less combative approach to the problem of Black dissatisfaction, which was focused as much on economic inequality as political inequality.

This was where Black capitalism came in. Fletcher sympathized with the anger in the ghetto, but thought that revolution was preposterous. “He was an unabashed capitalist, he was an anti-communist, and he saw fitting into the system as the best way forward for equality between the races,” said Golland, Fletcher’s biographer.

So when contractors started agreeing to the Philadelphia Plan’s terms and setting goals for how they would integrate, Fletcher felt vindicated. He set off on a victory tour with stops in Atlanta, New York, Phoenix, Chicago, and Baltimore, and made syndicated television appearances trumpeting the Nixon administration’s affirmative-action program, which was more aggressive than his Democratic predecessors’. The plan began to spread to other cities.

But with hindsight, it is easy to see his efforts were doomed. His work on Nixon’s behalf did not win him more influence. He’d almost single-handedly made the administration’s civil-rights agenda look sincere, but the president was still courting Jim Crow nostalgists. “A cabinet-level position for a Black man at that time would have undermined the Southern Strategy,” Golland writes, referring to the GOP’s growing dependence on white votes from former Confederate states. Plus, Fletcher’s success was making lots of people mad. “This thing is about as popular as a crab in a whorehouse,” said Everett Dirksen, the Republican Senate minority leader. The Philadelphia Plan was even more poisonous to white labor leaders and rank-and-file tradesmen, whose resistance to integration made them ripe targets for the coalition the GOP was trying to build even as it tried to placate the civil-rights community.

In the spring of 1970, hundreds of pro-war construction workers converged on lower Manhattan and attacked student demonstrators who were protesting the recent killings of four university students at Kent State. These workers were joined a few days later by local longshoremen, white-collar workers, and union leaders in a series of protests against the NYPD’s nonresponse to the student protests. Tens of thousands surrounded City Hall on May 20. Peter J. Brennan, a Nixon supporter who headed the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, followed up with a visit to the White House, where he presented the president with a ceremonial hard hat. Nixon’s embrace of the so-called “Hard Hat Rioters” enraged civil-rights leaders, but the president was starting to see the future of the GOP in these workers.

Brennan was an innovator in ducking Fletcher’s affirmative-action initiatives. He devised an alternative policy in New York that allowed local construction firms to exempt themselves from the Philadelphia Plan by coming up with their own more flexible integration goals. These so-called “Hometown Plans” were a sham, but they were good news for Nixon — if labor leaders complained to him about Fletcher being overzealous, he could point to this workaround as an alternative.

Still, firms that had failed to uphold their own integration plans were having their contracts terminated. To them, even the most modest requirements — one union was asked to increase its Black membership from six out of 800 — were an intolerable threat to the bottom line. Eventually, white labor leaders turned against Fletcher in force and made Nixon choose between them. “This fellow Fletcher, this appointee of yours, I’m sure you’re not responsible for what he’s doing right now,” said Brennan at a 1971 meeting with Nixon. “People are trying to do the right thing and being harassed.” For his part, Nixon saw Black people as ingrates for not rewarding him with more votes. “We’ve done more than anybody else,” he complained, “and they don’t … appreciate it.”

Fletcher was transferred out of the Labor Department in 1971 and stripped of his enforcement authority. “Fletcher had served his purpose,” writes Golland of how Nixon abandoned him. Meanwhile, the president’s relationship with Brennan was only getting stronger. Nixon agreed to withdraw his support for the Philadelphia Plan if the Labor leader agreed not to endorse his Democratic opponent in the 1972 election. At the time, this was practically unheard of. Democrats were the party of trade unions and could reliably count on the vocal support of Brennan and other white union leaders. But the Democratic Party’s association with civil rights under Kennedy and Johnson had caused a rift with the unions, which were now becoming more reactionary thanks, in part, to the Philadelphia Plan. Nixon made a devil’s bargain: Sacrifice Black equality to bring the white working class into the GOP’s tent. As agreed, Brennan declined to endorse George McGovern. He was rewarded by being named Nixon’s new secretary of Labor.

Brennan’s rise effectively killed proactive federal enforcement of affirmative action in the early 1970s. Fletcher stuck around after Nixon’s impeachment to help Gerald Ford, and eventually stumped for the former vice-president during his successful 1976 Republican primary campaign against Ronald Reagan. But Fletcher spent most of his next chapter in the private sector, capitalizing on his GOP connections and association with the Philadelphia Plan to become a prized diversity consultant for Fortune 500 companies seeking to hire more minorities.

Historians see the migration of white working-class voters to the GOP that Nixon brokered as crucial to Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential election. Its consequences include the most committedly right-wing Supreme Court majority in a generation — a cohort that makes no apologies for operating less as dispassionate jurists than as agents of the conservative movement. That Nixon’s Southern Strategy was hastened by an affirmative-action policy that he himself championed shows the deft and cynical way he played on both sides of the racial divide.

The idea that affirmative action would have a major economic component, that a nudge from the government would make Black capitalism an instrument of equality, had failed. And it was not just a Republican failure — as the parties underwent a realignment and Democrats became more fully the party of civil rights, they, too, abandoned the idea of labor-based affirmative action. From then on, affirmative action would increasingly be associated with education, on the assumption that a rite of passage through college would foment a robust Black middle class.

The deprivation that Black Americans faced in the post-Nixon years was relentless. In 1980, the Washington Post sent reporters to check on how Fletcher’s Philadelphia Plan was faring 11 years after its debut. They found a local welder named Ephraim Oakley, who had invested $15,000 in equipment under the impression that the federal government would ensure he could get work. But when he tried obtaining a union card with the local steamfitters, he was turned away. “Because those damned people won’t let me into their union, I’m losing thousands of dollars in work,” he said. “I’m being penalized for being a nigger.” The plan had made some of the trade unions more racially mixed — it was implemented in more than 30 cities — but federal enforcement had fallen by the wayside. “It absolutely failed,” said Golland.

Here was the main problem with “Black capitalism”: There wasn’t enough capital in Black communities to sustain it, ensuring that any asset-holders who set up shop were immediately underwater. Nixon never wanted to fund his initiative, either, making it little more than a politically expedient cover. “Black capitalism was a decoy,” said Mehrsa Baradaran, the Irvine law professor.

Ronald Reagan’s election was accelerating the white working-class migration to the GOP, a theme of which was the perceived overreach of the civil-rights movement. Cries of reverse discrimination against white Americans echoed across the country, fueled by the metamorphosis in large segments of the economy from blue-collar to white. The middle class was shrinking, the pathways into it narrowing. “In the context of diminishing rewards for the white majority facing a more and more tenuous grasp on the middle class, what is predictable is animosity,” said Touré Reed, who is co-director of the African American Studies Program at Illinois State University.

Meanwhile, other forms of affirmative action were also coming under assault. The first major challenge to affirmative action in higher education came in 1977, when the case of Allan Bakke reached the Supreme Court. Bakke was a white medical-school applicant in California who claimed he had been rejected from UC Davis because of a racial quota. Arguing that “reverse discrimination is as wrong as the primary variety it seeks to correct,” Bakke sought to eliminate the consideration of race in school admissions entirely. In an attempt to appeal to the Court’s conservatives, the lawyer for the school, Archibald Cox, reframed the legal basis for affirmative action by saying it served the interests of schools to allow them to curate a diverse environment. In the summer of 1978, Lewis Powell, the swing vote appointed by Nixon, split the difference: Davis’s quota system had to go, he ruled, but schools could still consider race in admissions as long as promoting diversity was their only objective.

The decision is credited with saving affirmative action in higher education. But it also narrowed its scope, such that its original rationales — redress for past discrimination and the end of material deprivation — were legally invalid and de-emphasized in the public consciousness. And it gave legal heft to trends that were already smothering the redistributive ambitions of the 1960s: a growing consensus that America did not owe anything to Black people.

In 1989, the Supreme Court delivered a decisive blow against affirmative action in the building trades when it ruled against the capital of Virginia’s policy of setting aside a percentage of contracts for minority-run firms. The GOP had effectively rebranded such policies as a quota system for unqualified Black people — or “affirmative Black-tion,” as Reed put it, quoting the derisive nickname used by Edward Norton’s neo-Nazi character in American History X.

In Texas in 1992, a Republican congressional candidate named Edward Blum lost an election. He responded to his defeat by blaming an unfairly drawn district, which made it too easy, in his opinion, for a minority candidate to triumph, and brought his case before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1996. The Court ruled in his favor, citing an illegal racial gerrymander — the first of many legal victories for the conservative activist, who made it his life’s mission to eradicate the consideration of race in any aspect of the law or education.

The national mood was in his favor: California voters passed Proposition 209 the same year as Blum’s first Supreme Court victory, outlawing affirmative action in any state or government institution. According to a 2020 study by researchers at UC Berkeley, Prop 209 led to a “cascade” of Black and Hispanic UC applicants into “lower-quality” public and private schools, resulting in steep long-term declines in their degree-completion rates and wage earnings.

This was all happening amid an influx of Asian immigrants in the 1990s, who were generally wealthier, more highly educated, and more attractive to white-collar employers than their predecessors in the post-1965 wave. White people seeking to justify America’s racial inequities had long pointed to this cohort — people with East or South Asian ancestry, often glossing over the more downtrodden Southeasterners and Pacific Islanders — as evidence that racism’s grip had loosened, or to argue that Black people were pathological and so deserved whatever grim fate befell them. But as Asian Americans established themselves in greater numbers, and in some cases started outpacing whites in income and educational achievement, many began to wonder why their successes had not earned them a proportional spot among the country’s elite.

The concerns of these Asian American activists dovetailed with decades of white conservative demagoguery, resulting in an almost absurd amount of quibbling over which of the highest-achieving students in the country deserved access to its most exclusive schools. “That’s one of the things I’ve always found personally disturbing about this,” said Reed. “I don’t think that most of the differences between these applicants are actually meaningful.”

Blum helped bring the case of a rejected University of Texas applicant named Abigail Fisher that ended up before the Supreme Court in 2016. Fisher’s lawyers argued that she was rejected in favor of less qualified minorities, and her defeat, amid revelations that her grades were less than sterling, was met with glee — hashtags like #StayMadAbby and pejorative nicknames like “Becky With the Bad Grades” took over social media. But Blum was already preparing his encore. He has since partnered with the ideological descendants of those 1990s Asian American activists, organizing them under the name Students for Fair Admissions, to argue that Harvard has a quota for keeping Asian applicants out. (In its less famous sister case, SFFA has claimed that the University of North Carolina’s recruitment of first-generation and low-income students discriminates against other applicants.)

If Blum’s challenges are successful, the effects would be devastating. Everywhere that such programs have been eliminated, their modest benefits have revealed them as far preferable to their absence: more minorities in jobs and in schools, and with greater access to the trappings of a middle-class life. It would also be a fitting, if grim, end to a policy that has been assailed and chipped away at from its very inception.

By the mid-1990s, Arthur Fletcher, fresh off a position as George H.W. Bush’s chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, found himself a lonely defender of the policy he helped create. “I would have been content to remain a footnote in history had the Republican Party, to which I have been loyal for more than fifty years, decided not to use affirmative action as a wedge issue in 1996,” he wrote. “Even my old friend Bob Dole, the Senate majority leader, who strongly supported affirmative action over the years, has turned against it in his drive to win the GOP nomination for president.”

Fletcher decided to throw his own hat in the ring as the only pro-affirmative-action Republican presidential candidate. But there was no appetite for what he was offering, 25 years after a GOP administration had made his affirmative-action program a centerpiece of its Black agenda. He technically ran in the 1996 election, but his campaign was doing so poorly that he had to bow out in 1995.

Fletcher died in 2005. His biographer told me his effects included newspaper clippings from almost every single story about Grutter v. Bollinger, the 2003 Supreme Court case that extended Powell’s decision to preserve affirmative action in higher education. “He wasn’t involved in the case at all, but it mattered to him,” Golland said. He’d also never changed his party affiliation, despite the reality that being a pro-affirmative-action Republican had become an oxymoron. Change from the inside was still possible, Fletcher believed. “From 1976 to 1995, that’s slightly less than 20 years,” Golland said. “Fletcher thought that if the party can change that quickly in such a short period of time, it can also change back.”

It has not changed back. Almost 20 years have passed since Fletcher’s death, and his beloved GOP has migrated even further away from his ideal. For all his misplaced faith in his party, the Kansan knew that Black people faced too many obstacles to become full participants in the economy without help. Today, you can barely find a Republican who’ll acknowledge the problem, let alone be affirmative about solving it.

A big reason why Fletcher’s affirmative-action idea was palatable to Nixon, and why Cox’s diversity rationale appealed to Justice Powell, was because both were a rebuke to the idea that a racially egalitarian America could be achieved through a mix of generous welfare programs and aggressive enforcement of anti-discrimination laws. Black capitalism’s central promise was that simply giving Black people access to the free market could allow them to rise up economically, but even that proved too much for white America. Black capitalism has now been replaced with an even hollower promise of diversity. “The main purpose of ‘diversity’ is to give white people a more diverse experience rather than to give non-white people an equal opportunity,” said Golland, Fletcher’s biographer.

Today, affirmative action gets treated even by Democrats like a child they’re mildly ashamed of. President Joe Biden supports it, and in 2021 his administration urged the Supreme Court not to hear the Harvard case. But while few in the party disparage it, they don’t embrace it, either, likely because of the mixed messages provided by polling. And they certainly haven’t adopted anything resembling an affirmative-action policy for the labor force. Even the most obvious solution to the Supreme Court striking down affirmative action, a renewed push for universal programs like in President Johnson’s Great Society, is complicated by the prospect of a familiar backlash against programs that are often coded as helping Black people.

When the Bakke arguments were heard in 1977, there was still much to be optimistic about: the major legislative victories of the civil-rights movement were just a decade old, and the new social order it birthed was still taking shape. People camped outside the courthouse to see how America’s most powerful institutions would respond to one of its first major challenges, and Powell’s ruling was greeted with relief. We live in a different world now. The anti-civil-rights backlash that followed has since calcified into a dominant theme of our politics. Betrayal of the movement is becoming more complete by the day — losses that we swallow more frequently now than before, but no less bitterly. “I’m assuming a bloodbath is coming,” said Reed. “But we’ll see. I hope not.”