This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On a recent spring morning outside the Pennsylvania State Capitol, a group of activists gathered to terminate the Constitution. Around 100 people drove in to Harrisburg from all over the state, showing up clad in white T-shirts and buttons depicting an American flag that nests COS, short for Convention of States, in the star area. Claiming endorsements from the likes of John Eastman, Sean Hannity, and Ron DeSantis, COS is a deep-pocketed right-wing movement that is quietly campaigning for states to call a constitutional convention, the first since 1787. “The government is out of control,” said Roy Fickling, a construction-industry retiree sitting on the balustrade. “It’s the only way to stop them.”

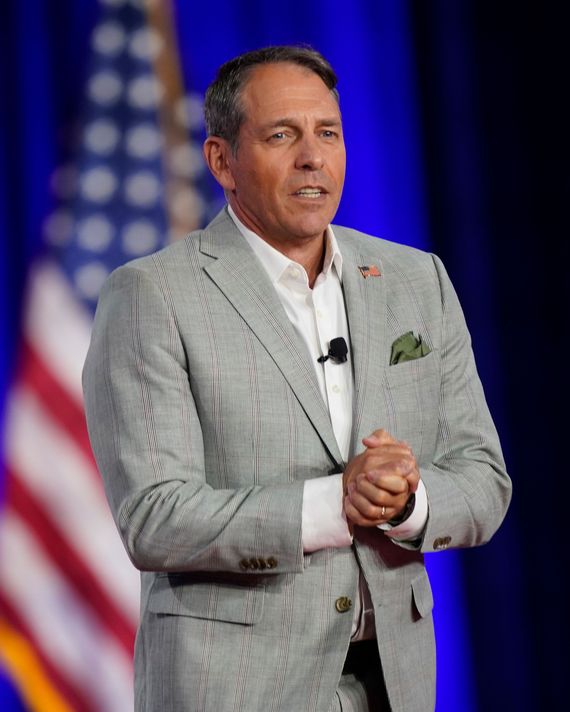

Just after 9 a.m., Rick Santorum waded into the crowd to deliver a speech about the “complete destruction” of America and the urgent need for a convention to radically amend the nation’s supreme law. “This is an existential fight,” said the Republican former Pennsylvania senator who is now a COS senior adviser. “It’s not about politics. The people on the left do not want the same America as you do. This is about good and evil.” The crowd applauded. He then went on to talk about trans issues. “The reality is this is a moment where we need patriots, just like we did in 1776.”

Activists divided up piles of manila envelopes and fanned out into the capitol to lobby lawmakers or, as a man dressed as Benjamin Franklin put it, “harass some legislators!”

Inside those envelopes is information about what they believe is the cure-all for the nation’s ails, from ballooning debt to a tyrannical federal government: Article V of the Constitution, which lays out two amendment mechanisms. The first has been used successfully 27 times; Congress passes an amendment by a two-thirds vote in each chamber, which is then ratified by three-fourths of the states. The second way is a little-known, never-before-taken path: Get two-thirds of the states to pass resolutions calling for a convention where delegates from the states can propose amendments. To anyone disheartened by congressional gridlock, Article V may seem like a seductive idea. While proposed amendments would theoretically also have to be ratified by 38 states, that is cold comfort to the legal scholars who see calling a convention as a constitutional crisis waiting to happen. “The only precedent is the Philadelphia convention from 1787, and they ended up junking the Articles of Confederation and writing a whole new constitution,” said David Super, a professor at Georgetown Law. So far, COS has won 19 states of the 34 necessary to force such a convention.

As outlandish as it may seem, the 20th century saw three major Article V movements, two of which reached 33 and 32 states. While it might sound like a fringe idea, so too did the independent-state-legislature theory, which is now before the Supreme Court. The Second Amendment was viewed by many legal scholars as a dusty old clause regulating militias until the Supreme Court’s 2008 Heller decision, which affirmed an individual right to bear arms. That same year, a federal judge laughed at the lawyer arguing for Citizens United. Abortion was a constitutional right for half a century until Dobbs. Like the architects behind the previous legal efforts, COS is grinding away toward a far-off goal, just waiting for the right moment. “This is the army, in my opinion, that saves America,” said COS leader Mark Meckler in an interview with Tucker Carlson, who endorsed the idea.

Meckler projects himself as the crusader of what he calls the “largest self-governing, grassroots army in American history.” But as he crisscrosses the nation to lobby lawmakers, he does so with a persona antithetical to his peers on Fox News: warm, calm, even ordinary. He often jokes that COS’s only “big fancy high-rise office” is the one above his garage and posts videos from the road while eating barbecue in Raleigh. “I’m all alone, but I’m thinking about you guys,” he says. “It’s almost like you’re with me.”

It’s quite the façade. While Meckler says COS is funded by grandmas sending $5 per month, his group is in fact bankrolled by tens of millions of dollars in dark money. (He did not respond to requests for comment.) Just like his days as a leader of the tea party, Meckler is part of a vast web of billionaire-funded right-wing efforts pushing radical movements to consolidate power under the guise of populism — this time armed with what Santorum called a “live weapon” pointed at the nation’s legal heart. “In my area of South Dakota, COS would be synonymous with dog shit,” said Lee Schoenbeck, a Republican state senator who has been targeted by COS. “They’re well-meaning folks; they’re patriotic,” he said about COS’s supporters. “But this fraud is taking advantage of them to line his family’s pockets … He’s just another scam artist.”

Thirty years ago, Meckler had ditched the studded dog collar he wore as a Clash-loving law student, but his inner rebel was still alive. In 1993, he and his second wife, Patty, opened Cafe Mekka in Nevada City, an Austin-like outpost in California Gold Country. He seemed as progressive as the staff, former employees say, defending gay people against bullies and, according to a local journalist, hosting police and activists at a sister café in San Diego to discuss racism after Rodney King’s beating. “We always thought he was just dyed-in-the-wool liberal,” said Darin Barry, a former employee.

At the same time, he and Patty, a former saleswoman at Minolta Business Systems, were exacting bosses. They quizzed employees on different coffee beans and devised scripts for interacting with patrons. “If a customer asked, ‘What’s the cheesecake?,’ we couldn’t just say, ‘Chocolate cheesecake.’ We had to say, ‘This is Belgian-chocolate cheesecake layered with white chocolate,’” said Jay Henslee, another former employee. “They’re both very phenomenal salespeople.”

In the ’90s, a friend introduced the Mecklers to Herbalife, the multilevel-marketing company that has long been characterized, against its denials, as a pyramid scheme. While they nominally sold weight-loss supplements, Herbalife hawked the American Dream to distributors. Money, freedom, independence — all you needed to do was work hard, believe, and stay away from the doubters. In late 1997, the Mecklers sold the café and became obsessed with getting to the top of Herbalife, traveling to international conventions and advertising on local right-wing radio. By 2002, Meckler had qualified for the “president’s team,” a group that represented less than one percent of distributors who brought in at least $200,000 per month for several months at a time, as Mother Jones would later report. Still, it wasn’t enough, and the Mecklers were also running a winter-sports-equipment manufacturing company that left them yelling and angry, recalled Barry, who also worked there. But then Herbalife prospects would show up at the factory. “All of a sudden, bright Colgate smiles would come across both of them and they would turn into Doris Day and Robert Redford,” said Barry. “They were turning into monsters.”

Meanwhile, Nevada County was undergoing its own rapid transformation. Once a mining and timber hub, the Sierra oasis began in the ’70s to attract a surge of white-flighters from Southern California and dot-com nouveaux riches from the Bay Area. To mitigate the impact of that growth, in 2000 the county initiated a benign planning and conservation effort called Natural Heritage 2020. It set off a political firestorm and galvanized the county’s emerging radical right, a small but vocal cohort who baselessly claimed that NH 2020 was a U.N. conspiracy to confiscate property. People hung tea bags from their hats at parades, and NH 2020 proponents were hit with death threats, sexist mailers, antisemitism — the backlash was so intense that the county eventually killed the program. Leading the NH 2020 opposition was a coterie of right-wing figures who, locals say, were connected with Meckler and his father, Stan, though the latter denies they had any involvement.

At the same time, Meckler would gather monthly with friends to talk politics, according to Jon Blinder, who was then a close friend of Meckler’s. “Mark was always pretty thoughtful, what I would consider a real-world conservative,” said Blinder. Then 9/11 happened. “He got radicalized from that,” Blinder said, “and he has not backed down.” Meckler grew disillusioned with both parties and once, according to Blinder, said the U.S. should “bomb the whole Middle East and be done with the Arab problem.” By the time Rick Santelli called for a “tea party” in early 2009 to protest bailing out homeowners during the Great Recession, Meckler had completed his journey to the right.

Meckler and his family drove to Sacramento with signs to join a protest of some 150 people at the state capitol. In the following weeks, he began reaching out to tea-party organizers across the country and got connected with Jenny Beth Martin and Amy Kremer, freshman activists in Atlanta, and co-founded the Tea Party Patriots. It would soon become one of the most influential national tea-party groups, helping to mobilize the angry conservative grass roots to the National Mall and to congressional town-hall meetings about Obamacare. During the midterms, Meckler and his allies helped shift the GOP to the right, ushering in a freshman class of House Republicans who vowed “no compromise” and who, in a move that is today routine, took the debt ceiling hostage. But he wanted to go further, laying out in a 2010 address to the Nevada County TPP his 40-year-plan to take back the country. Now wearing a cowboy hat and horseshoe mustache, Meckler was the rare face of a decentralized movement. “All of a sudden, he found himself in a position of real power,” Blinder said.

All throughout, Meckler presented himself as an independent, small-town internet-marketing lawyer whose entry into politics was stoked purely by outrage. But a report found that Meckler, prior to the TPP, had developed an internet-marketing firm that sought to build email lists for GOP political candidates. The California Bar suspended Meckler’s law license from 2001 to 2006 for failing to pay fees and comply with state legal training, and five longtime Nevada County lawyers I contacted said they could not speak to his legal practice. The TPP’s grassroots image was also suspect. In 2010, the group claimed to have 2,300 local groups, but an investigation by the Washington Post could only verify less than a third of them. A series of investigations by Mother Jones exposed the TPP’s mysterious finances, its GOP-tied operations, and the private jet flying around Martin and Meckler.

Meckler’s downfall was as quick as his rise. In December 2011, Meckler was charged with a felony after trying to board a flight from La Guardia with a gun. (He soon pleaded guilty to a lesser disorderly-conduct charge.) Two months later, he resigned from the TPP, claiming that his “personal fight” to keep the organization grassroots had “failed,” and implored TPP leadership to halt its “attacks” against him, including, he claimed, from Martin, with whom he was on a book tour. Among many who knew him in California, his tea-party transformation was bewildering. “When he got involved with the tea party, I was like, Oh my gosh, that doesn’t match up. But it also didn’t really surprise me because he kinda morphs,” said Sarah Hendrickson, a former Cafe Mekka barista. “He’s kind of a chameleon. If somebody needs something, he’s that.”

This made him useful to right-wing donors, namely Eric O’Keefe, a Wisconsin investor with deep ties to David Koch and a prominent opponent of campaign-finance laws. At the height of the tea party, he reached out to Meckler and co-founded a nonprofit called Citizens for Self-Governance along with Tim Dunn, an Evangelical Texas billionaire. In 2013, they backed a tea-party lawsuit against the IRS for allegedly targeting conservative groups. Then Meckler met Michael Farris, a conservative lawyer who would go on to circulate an influential draft of the Republican-led lawsuit that asked the Supreme Court to overturn the 2020 election by tossing out the results from Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Until last year, he was president of the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative Christian legal machine that helped draft and litigate the Mississippi abortion ban that overturned Roe v. Wade. (ADF is now taking aim at the abortion pill mifepristone.)

Looking back on the tea party’s ultimate failure to stop Obama, Meckler says Farris told him, “‘We have a structure problem, not a personnel problem.’” Farris’s solution was to tear up the Constitution, and in 2013, they co-founded the Convention of States Project. That year, Meckler pitched the idea to the American Legislative Exchange Council, a clearinghouse for conservative policy, which became a key proponent, and COS began racking up state resolutions in the South and endorsements from Marco Rubio, Mike Huckabee, and James O’Keefe. In 2016, COS hosted a mock convention, where over 100 state lawmakers adopted amendments that would, among others, repeal the income tax and allow a vote of 30 state legislatures to nullify federal laws. Critics of COS “actually said something truthful,” Meckler told Mark Levin, another supporter. “They said, ‘This is intended to reverse 115 years of progressivism,’ and we say, ‘Yes, it is.’”

Among progressives, there is some, albeit far more limited, convention interest. Last week, California governor Gavin Newsom joined in, calling for a convention to propose a gun-control amendment. The most prominent left-wing proponent is Lawrence Lessig, a Harvard Law School professor who, in 2016, debated alongside Meckler and argues that a convention is the only way to achieve fundamental democratic reform because of gerrymandering, money in politics, and the Electoral College. “The anxiety many have — and I think it’s fair — is that a convention will be minoritarian,” Lessig said, referring to the lopsided power small states would have if each state gets a vote. As such, “it’s really critical to embed a democracy constraint on the convention process.” Still, whether a convention would abide by any constraints, especially in such a volatile political climate, is an open question.

So, too, is just how close we are to a convention. Another Article V movement calling for a balanced-budget amendment claims 28 state resolutions. More alarming still: Former Wisconsin governor Scott Walker, exploiting the Constitution’s lack of rules for how to count resolutions — must their purposes match? Do they ever expire? — argued in 2020 that we already reached the 34-state threshold by aggregating unrelated resolutions all the way back to 1789. In March, Jodey Arrington, the Republican chair of the House Budget Committee, introduced a bill requiring Congress to call a convention, arguing we reached the threshold in 1979. It’s unlikely to go anywhere with Democrats in control of the Senate, but “if Republicans keep the House and take the Senate in 2024,” said Super, the Georgetown Law professor, “it’s a very good chance they’ll do it.”

All along the way, Meckler pushed a familiar line that this effort was coming from the bottom up. “We serve the grass roots,” Meckler told a room of state legislators at a COS workshop in 2015. “That’s our job: to give them tools.” In reality, there is nothing grassroots about COS. The Center for Media and Democracy tells me that it found that COS, through three of its nonprofits, drew in over $58 million in dark money between 2016 and 2021, including from funds tied to networks of the Kochs’ and of Trump’s “judge whisperer,” Leonard Leo. In February 2021, Parler — co-founded by Rebekah Mercer, whose family is also a COS donor — hired Meckler as interim CEO to relaunch the site after it was deplatformed for allegedly stoking the attack on the Capitol. Meckler said he became friends with Santorum while hunting with Foster Friess, a Christian-right megadonor from Wyoming. Meckler and Patty, who fundraises for COS, together made $1.77 million from COS, according to four years of its tax returns. The home office that Meckler jokes about is inside a house in an Austin suburb that was transferred to him in 2019 by COS director Tim Dunn, who also financed an associated $718,315 loan, according to county records.

Meckler’s claims about a constitutional convention are similarly misleading. In the convention that COS envisions, proposed amendments would be “limited” to fiscal restraints, term limits, and limiting the power and jurisdiction of the federal government. Except there is nothing in Article V that limits the scope of a convention. As Meckler put it in his own 2012 book that he co-wrote with Martin about starting the Tea Party Patriots, people “are rightfully fearful that an open-ended convention could produce changes that would alter the very framework that guarantees us freedom.” As such, he supported writing a new amendment permitting single-issue conventions to ensure one could be held “without fearing damage to the fundamental fabric of our governing institutions.”

No one is more incensed about Meckler’s project than the right. This year, COS filed Article V resolutions in at least 24 states, but so far none have succeeded. That’s because COS has drawn fierce resistance from some Republican lawmakers and activists who fear that a convention could jeopardize their priorities around gun rights, abortion, or the whole Constitution. Phyllis Schlafly, an icon of the conservative movement who defeated the Equal Rights Amendment, likened such a convention to “playing Russian Roulette.” Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia concurred, saying, “Whoa! Who knows what would come out of it?” Glenn Beck has reversed his support. The John Birch Society, the advocacy group that radicalized the modern right, hosts educational tours to teach people about the realities of Article V. (Meckler calls the John Birch Society “‘the J-BS,’ because frankly they’re so full of it,” and accuses it of being “in bed” with “radical leftist” organizations that oppose a convention.)

Using tea-party tactics of the past, COS has gone scorched-earth against its opposition. It has threatened to primary hostile Republicans. For the first time, last year, COS started to finance elections, spending over $1 million on midterm primaries in Idaho, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Wyoming, South Dakota, Texas, and Montana (where COS was accused of violating campaign-finance laws before settling in February), according to the Center for Media and Democracy. In South Dakota, COS inundated voters with mailers accusing several Republican lawmakers of supporting trans education in schools. While COS claims nearly 2.5 million petition signatures, at least four lawmakers said they have received bogus petitions or emails. (Meckler has said that its petition system is imperfect because “somebody can fill out anybody else’s name and information, and I can’t stop that,” but he strongly denied that COS had fabricated any petition signatures itself.) In 2018, a COS-funded political action committee sent out a robocall suggesting that David Johnson, a Republican South Dakota state senator, was a domestic abuser, among other claims, which Johnson says is “a flat-out lie.” (Montana state senator Theresa Manzella said that she almost resigned after the alleged harassment she faced from COS supporters.) “I equate it to the old snake-oil salesman,” said Johnson. “It’s quite a scam, but that’s politics in the United States of America.”

In Harrisburg, I asked Santorum about these allegations. “Some people get passionate and can say things and do things that are unfortunate,” he said. “Do mistakes happen sometimes when someone gets carried away? Of course it happens. It happens in every organization. And we try to limit that. And it’s part of our creed to make sure that respect is at the forefront of everything we do.”

At the end of a Facebook video from earlier this year, a viewer asks Meckler, “What’s taking so long?” He smiles. “The Founders intended this to take a long time and to be difficult,” he says. “We can make it faster by you getting engaged.” Before he signs off, he shares a comment that he says he received on the road. “People say, ‘It seems like when we see you [in the media], like, it’s really you’ … I just want you to know how much I appreciate that, how much it affects me in my heart,” he says, his hand on his T-shirt-clad chest that says GENUINE AMERICAN PATRIOT. “Because it’s not an act. This is just me … More important than anything else is to represent you, the grass roots.

“And if you want to represent,” he says, tipping his black camo COS cap that sells for $25.99, “remember — you gotta wear the gear.”