This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

“I have some questions about some group I found,” Ethan Melzer wrote on Discord in February 2019. Deep into occult forums since he was a kid, Melzer was in a channel on the encrypted-messaging app looking for information on the Order of Nine Angles. Founded in the 1960s in England, the group takes an omnivorous approach to the occult and the far right, picking from the worst of Satanism, Nazism, and white nationalism. “So let me get this straight,” Melzer wrote to one O9A adherent. “There [are] satanic nazi edgelords.” O9A’s true size is unknown and its beliefs vary widely, but a common goal is to join a gang, terrorist plot, police force, or military unit, then stir as much chaos as possible to accelerate the fall of western civilization.

By the time he sent that message, Melzer had already signed up with the Army. To his loved ones, it looked as if the 20-year-old was finally on a path to a normal life. His baby face and pink cheeks did not tell the story of the years lost to abuse, meth addiction, and violence by his own hand. In a period he would call a “total blur,” he sold drugs to fund his habit and said he joined a Louisville chapter of the Bloods gang. Authorities later claimed that he shot a dealer in the arm after running off with an ounce of weed. But by late 2018, he had found stability at the federal career-training program Job Corps in rural Kentucky: early wake-up calls, cafeteria meals, a reliable dorm bed. A counselor there described him as a “good kid,” one that you “wouldn’t mind dating your daughter.”

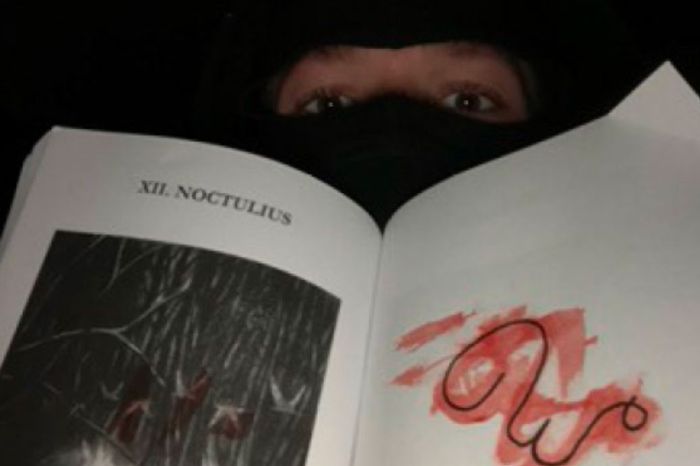

In June 2019, he reported for active duty at Fort Moore in Georgia, where he signed an enlistment statement disavowing any allegiance to extremist groups. Online, though, he was learning everything he could about O9A while vetting newcomers on Discord. “Do you believe in survival of the fittest?” he asked. “What is fascism to you?” Other extremists on Discord warned him he was “playing with fire” by staying in contact with O9A while in the military. Melzer didn’t care. Shortly before he shipped out to a base in Italy that fall, he bought a copy of the Order’s satanic bible. He smeared blood on his favorite passages and kept it throughout his deployment.

But life in active duty as a private wasn’t quite what he hoped for. He socialized little and drank alone. In his second life online, he was frustrated by his lack of opportunities to act on behalf of O9A. In a conversation on how to start a race war, he wrote, “Can’t really do anything when I’m in fucking Italy.” For a while, he became too depressed to visit the extremist chats that had enticed him for the past year. Then COVID hit Northern Italy and Melzer was stuck in the barracks under lockdown, where he got sucked back into far-right chat rooms. While his platoon slept around him, he plotted its demise.

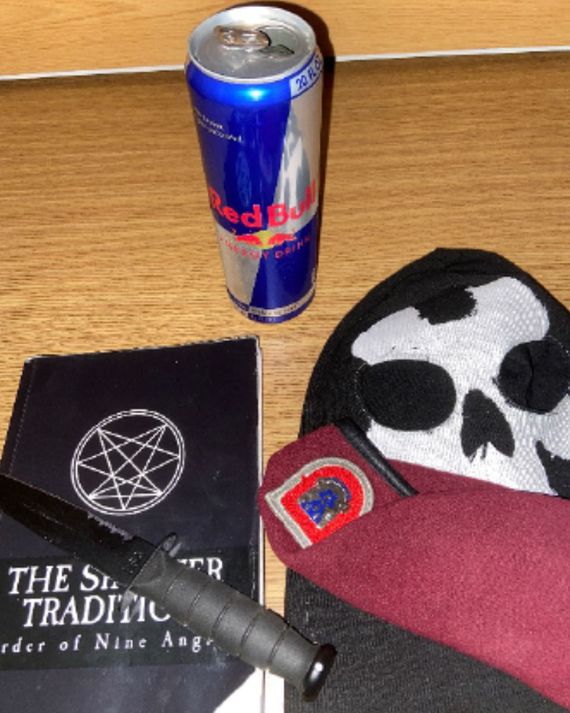

On April 21, 2020, Melzer accessed a new O9A group on the encrypted app Telegram. Its moderator was GvlagKvlt, a Canadian who said he had become radicalized after getting wounded as a paratrooper in Iraq. To join, Melzer had to prove that he was really a soldier. He sent GvlagKvlt a picture of his Army beret with his battalion insignia next to a knife, a 20-ounce can of Red Bull, a ski mask with a skull design, and his O9A manifesto.

He was in, and over the next two weeks, Melzer downloaded snuff videos and neo-Nazi propaganda. (He was not the only active-duty member in the chat: The next month, an Ohio National Guardsman was discharged after he was found to be in the same Telegram room.) Melzer told GvlagKvlt that he hoped the chat would become “an actual active nexion,” their term for a group that turns talk of far-right violence into a reality. He was getting into more dangerous territory and tried to act normal on the base, knowing “to be careful as fuck just because I feel like shit would be harsher considering my current circumstances.”

Then on May 6, Melzer and GvlagKvlt realized they had an opportunity to pull off a surprise attack on his fellow soldiers. Melzer’s commanding officer informed the platoon that it would deploy in three weeks to guard a U.S. base in Turkey. The soldiers studied classified information on the base’s choke points and how their unit, just under 40 men armed with M4 rifles, should respond to protests, head-on attacks, and threats from within. To game out the strategy, the soldiers practiced on a cardboard model of the terrain that Melzer helped build.

After signing a document informing him that disclosing this information would be a federal crime, Melzer passed on the details of his deployment to GvlagKvlt, who prodded him for more: “Okay, how many people will be in the convoy, are you gonna be there? What will be carried … Whats the plans.”

Melzer answered the questions and the plan gained traction. “Are we literally organizing a jihadi attack,” he asked Melzer in a direct message on May 24.

“Yes probably,” Melzer wrote.

“That’s kinda baste,” GvlagKvlt responded. He asked Melzer once more if their proposed attack on the base was real. He asked Melzer if he was ready to die.

“Who gives a fuck,” Melzer replied. “The after effects of a convoy getting attacked would cover it … I would’ve died successfully.” If they pulled it off, he saw the attack as a turning point in 21st-century history, one that would spark “another 10-year war in the Middle East” — one that would “definitely leave a mark.”

Taking on close to 40 U.S. Army soldiers trained to protect the base from internal and external threats was a tall order. At first, Melzer suggested an attack on his fellow soldiers on their way to the base but realized he would get wiped out immediately in that scenario. To get more time to prepare, Melzer floated attacking the replacement unit relieving his platoon of its duty in two-to-four months, a period during which he would look for weak points to target on the base. GvlagKvlt proposed an ambush from a nearby mountain, where their recruits to the plot could spread out and attack from high ground. Melzer believed that would leave “every fire-team essentially crippled.”

Now they just needed the guys to do it. GvlagKvlt gathered together four other users, including his girlfriend who went by the name Red Hourglass. Melzer hoped to boost their numbers to at least 20. Once he was in Turkey, Melzer promised to give more information via a burner cell, as their phones were taken during patrols. But the deployment scheduled for May 28 was mysteriously delayed. Melzer didn’t seem worried to the other chat members. Red Hourglass asked him, “What makes you think that you can actually get away with fucking with the US military.”

“Because I fly under the radar [and] act completely normal around other people outside and don’t talk about my personal life or beliefs with anyone,” he replied. Little did he know that Red Hourglass was an FBI informant.

When he was arrested on June 10, 2020, Melzer had his phone and O9A materials on him, under the impression that he was boarding a bus to deploy to Turkey. On the plane ride to Manhattan, where he was indicted, he agreed to speak to FBI agents without his attorney. At first, he denied that he was a member of O9A and dismissed the plot as the conversation of a bunch of “jokers” with a dark sense of humor. But he eventually admitted to sending the messages revealing security information about the base in Turkey in order to kill his fellow soldiers.

Federal prosecutors set out to frame him as the latest in a growing roll call of young soldiers whose tumble down the online hole of far-right extremism had threatened national security. They also placed Melzer within the context of past acts of violence from members of the Order of Nine Angles. Because of its cell structure and the ability for young men to radicalize themselves online, it is difficult to know who is for real and who is pretending. (For example, at various points in the plot on Telegram, Melzer claimed to have infiltrated the Bloods, an ISIS chat group, and an “insufferable” antifa cell in the U.S.) But in recent years, O9A materials have been found in the search history and homes of men in North America and Western Europe who were charged with terror offenses.

Melzer’s arrest was also representative of the FBI’s heavy use of confidential sources after 9/11 to carry out sting operations against supposed terrorists. The informant, Red Hourglass, had already infiltrated the O9A group chat when Melzer entered to set up the attack on his fellow soldiers. Once the informant saw a threat emerging, she teased incriminating information out of Melzer. On May 23, Melzer sent a message to the group chat, writing that he wished to “stir something up” while stationed abroad. “Stir something up with what?” the informant replied. Melzer seemed frustrated. “Ok let me be as direct as possible,” he wrote. “IF YOU KNOW ANYONE IN TURKEY TELL THEM THIS INFO there.” The informant again pushed for more details. “There is a convoy coming through Turkey soon and date and time will be given soon. Goddamn,” Melzer replied.

The informant tried again days later by playing dumb. “So for the sake of clarity (and because I’m an idiot so I want to make sure I’m not misunderstanding) — you currently stationed in Vicenza with U.S. army will be deployed to Turkey soon,” she wrote. “A ‘convoy’ (your own convoy?) will be going through Turkey, and on Monday you’ll be receiving the date and time the convoy will be going through Turkey. And you’re going to dm me said time and date so that I can pass it along to any jihadis in Turkey. Right?” When Melzer confirmed the details, he broke the law against sharing classified information.

Without any money for an attorney and facing a life sentence if convicted, Melzer turned to the Federal Defenders of New York, the public-defender office for people accused of federal crimes in the city. Unlike other extremist conspiracies in which FBI informants were essential to moving the plot forward, Melzer’s attorneys did not claim entrapment. But as his legal team was given the evidence of the chats, it saw a potential defense involving another chat member. The person who brought Melzer and others together for the suicide attack was not who he said he was either.

GvlagKvlt had never served in Iraq. In fact, he wasn’t even old enough to remember the war. Documents disclosed by prosecutors showed that he was a 15-year-old living in Canada who, three months before vetting Melzer to join his Telegram channel, was arrested and hospitalized for psychiatric care.

In retrospect, there were clues to his juvenile mind-set. Throughout the chats, the teenager was frequently dropping in immature jokes about his penis and going off on immature rants:

“PRAISE THE LORD OF PUSSY

ALL SEEING KING OF CUM

CUM IN YOUR MOUTH

CUM ON THE COUCH

CUM IN YOUR MOM

CUM IN YOUR BONG

HOW DO I SUMMON A CUM DEMON”

With that bombshell in hand, Melzer’s defense strategy was clear: Raise the many flaws in the conspiracy showing that it would never have come to pass in the real world.

Aside from Melzer, the informant, and the teenager, there were three others interested in carrying out the attack. According to a source familiar with the case, one was a user named Gubaq who was involved in the later stages of planning the attack. But he was cut out from the plot after admitting that he too was a teenager. At home in South Carolina, he was pretending to be someone else.

Another was Kurt_Cobani, who was purportedly a member of a far-right Turkish nationalist group. According to boasts from the 15-year-old GvlagKvlt, he was also linked to Al Qaeda. But Melzer’s attorneys alleged that the prosecution provided no information to back up Kurt_Cobani’s claim that he was a Turkish militant. They also noted that Kurt_Cobani refused to participate in the final conversations coordinating the attack.

The last man in the conspiracy was a user named Jaww who presented himself as a far-right agitator living in France. But he admitted to the group that he did not know anyone in Turkey aside from Kurt_Cobani. It is unclear if Kurt_Cobani and Jaww were actual threats — or even who they said they were — as that evidence is subject to a protective order.

Melzer’s attorneys also raised questions about his commitment to carrying out the strike. On May 29, when his platoon was sitting around waiting to go to Turkey — the deployment was delayed for the FBI to catch Melzer — he lied to his Telegram cell, saying that he left Italy and was en route to Turkey. On the flight home, Melzer told FBI agents that he had gotten scared and lied to say that the attack was in motion in an attempt to cut off contact with the cell. He was worried that the informant, the teenager, and the conspirator in Turkey were actually serious about pulling off the attack.

His attorneys pointed out other holes as well. Melzer told his co-conspirators that the unit they were attacking would “only” be armed with M4s, the standard-issue infantry assault rifle. Even with the surprise of an ambush, a handful of men would need to take out over three dozen soldiers trained to respond to exactly the kind of attack they were planning. And as the date of the attack drew closer, they had not convinced anyone else to join their suicide mission. Four days before Melzer’s arrest, the conspiracy’s teenage leader wrote, “Other than a really basic plan of attack and a lot of info, we don’t really have much else. And a plan of attack doesnt work without people to..you know, do the attack.” The informant also doubted their potential, calling the team a “confederacy of dunces.”

Over two years of pretrial motions, Melzer’s attorneys tried to get documents on the informant, the teenager, and the juvenile nature of the full chats submitted as evidence. But the day after Melzer’s attorneys filed a motion to admit evidence revealing the young age of the mentally unstable conspiracy leader, the prosecution offered a deal. Melzer agreed to plead guilty to attempting to murder U.S. service members, providing and attempting to provide material support to terrorists, and illegally transmitting national-defense information. In exchange, the maximum sentence would be reduced from life to 45 years.

It would be up to Judge Gregory Woods to decide how much time Melzer should serve behind bars. His lawyers pushed for 15 years of imprisonment followed by ten years of supervised release, arguing that Melzer’s age and the aspirational nature of the online plot were mitigating circumstances. They also cited his childhood of abuse and neglect, raised by a mother who was suffering from undiagnosed bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. To cope, she drank heavily — as did a number of boyfriends who abused Melzer. Things only got worse when, in middle school, he realized he was gay. “The only thing I knew for sure was don’t be gay,” he later told a caseworker.

On March 3, 2023, Melzer appeared in Manhattan federal court to learn his fate. “I wish I could fix what I did,” he said, apologizing to his family and the men he once wanted to kill. “But I can’t.” When it was his turn, Melzer’s attorney called the plot “muddled” and claimed that the proposed sentence was excessive, citing an eight-year sentence handed down by the same court for a man who plotted to shoot up a military recruiting station and join the Taliban.

Woods was unconvinced. “Mr. Melzer now expresses remorse. I, frankly, do not believe him,” he said. Melzer’s hands were shaking when he learned he would receive the maximum available sentence: 45 years in federal prison without the possibility of parole.

Melzer and his attorneys declined to speak for this story, as they intend to appeal the terms of the sentence. But Michael Sherwin, the former acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, described the sentencing as an overreach. Sherwin, who previously served in an intelligence role for U.S. Central Command, said he has doubts about just how sensitive the information was that Melzer had passed on. “I’ve served in Turkey. Most of these bases have thousands of foreign actors on these bases,” he said. “Nothing is secret. You could Google these locations.”

Since he left the Justice Department two years ago, Sherwin has been a vocal critic of what he sees as overzealous prosecutors charging terror cases. As the lead prosecutor tracking Cesar Sayoc — the strip-club DJ who sent pipe bombs to Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Hillary Clinton — he noticed some inconsistencies with that 20-year sentencing and Melzer’s. “Melzer got 45 years in the same district in New York — the same offices where Cesar Sayoc pleaded guilty as an adult,” he said. “You need to step back and say to yourself, Is there equitable sentencing here? You have to look at these people; were they similarly situated? Were they treated properly and equally? That being said, no — absolutely not.” The prosecution declined to comment on the case.

Earlier this year, Melzer was transferred to a medium-security facility in Indiana, where he will be until the day before Thanksgiving 2058. Those who know him say he has denounced the ideology that led him down a path of self-destruction. He has also come out of the closet to his parents. “I spent my whole life as a fish out of water, and now I am comfortable in my skin,” he told his caseworker. His family members, gutted by the revelation of his horrid plot, have finally accepted him. “Whoever loves Ethan, I will love them too,” his mother wrote to the judge. “I just can’t stand not having him here anymore.”