People still weep, no matter how many memories have come and gone, when they talk about my friend and neighbor James Davis, the city councilman who was shot to death inside City Hall 20 years ago, assassinated by a political rival.

The tears welled up in Geoffrey Davis as he recalled his older brother’s murder, and how they’d told morbid jokes about the real risk of the same kind of violent death that struck down Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and other famous civil rights leaders.

“We discussed this with other great leaders of the past, that this could be a possibility. And then we’d crack jokes,” Davis told me. “He said, ‘If something should happen to me, you know what? Your name is going to be James Davis’s little brother.’”

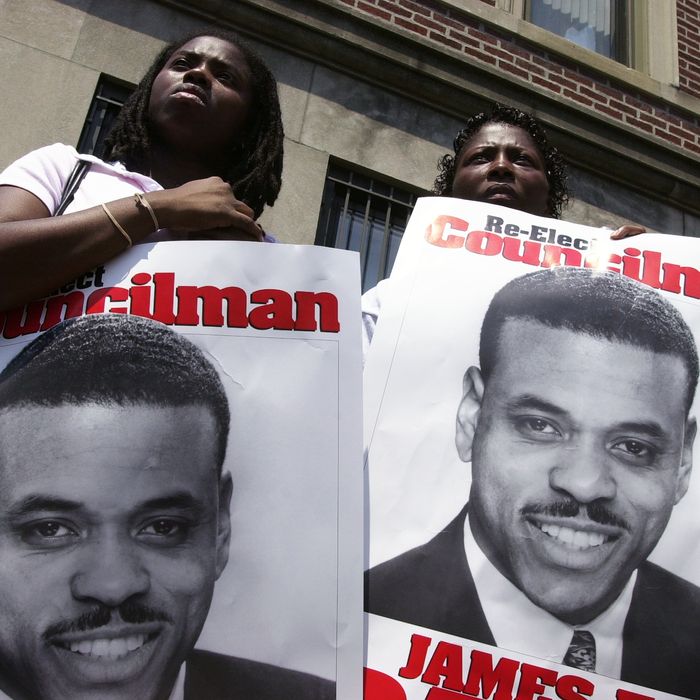

Morbid jokes aside, Davis lived and died as a soldier in the city’s historic, successful battle to drive down street violence in the 1990s, first as a policeman; then as a community activist who founded a small church and flooded Central Brooklyn with protests, prayer vigils, and a seemingly endless supply of posters with his face on them saying “Love Yourself: Stop the Violence;” and finally as an elected official.

At the time, New York was turning the corner on crime — in 1997, homicides dropped more than 22 percent — but there were still far too many shootings and deaths in East New York, Bed-Stuy, Crown Heights and other low-income Brooklyn neighborhoods. Davis was one among many public-minded young activists — including me — who were buzzing around Central Brooklyn in the 1990s, starting or joining organizations, forming alliances and launching movements, many of them aimed at violence reduction.

I first met Davis when, after working on a string of economic development projects, I quit my job to make my first and only bid for public office, running in the Democratic primary for city council in 1997 against a longtime incumbent named Mary Pinkett. Davis called me up, came to my house, pledged his support — and then filed a lawsuit to throw me off the ballot because it turned out he was running for the same seat.

Such were the politics of Black Brooklyn at the time. Davis and I both tried hard, and I rounded up endorsements from the New York Times, the Amsterdam News, and the League of Conservation Voters, along with nearly all of the local state and federal officials. In the end, I got about 3,000 votes and Davis around 2,000; Pinkett trounced both of us with about 5,400, reducing a year’s worth of excruciating hard work to a single sentence in the Daily News: “Incumbent Mary Pinkett easily beat James Davis and Errol Louis, two newcomers.”

The campaign sparked a political blaze in Brooklyn. A year after I lost, I met a young attorney named Hakeem Jeffries, who was about to launch the first of three runs for state Assembly. In that same year, Davis caused a sensation by coming within 677 votes of unseating Assemblyman Clarence Norman, who doubled as chairman of the Kings County Democratic organization. Kevin Parker won a senate seat in 2002 and my friend Karim Camara, a staffer to Norman, succeeded him in 2004. Eric Adams, an NYPD officer who’d made an unsuccessful bid for Congress in 1994, began the planning that would land him a state senate seat in 2006.

“It was a great time. Those years — I call it the kick-in-the door years in Brooklyn — were so fun. We were all young, we were all hungry. We all, in our own ways, wanted to serve, whether it was that you ran for office, or you wanted to work in City Hall,” says Lupe Todd-Medina, a political consultant who formerly worked in the City Council press office. “You had all these young guns who were kind of saying to the establishment, to the Democratic Party of Brooklyn: ‘No more. We’ve been waiting, you haven’t given us a chance, so we’re just going to take it.’”

“Brooklyn politics were bare knuckles. There were some notable rivalries from different camps,” Adams reminisced with me recently. “What was unique with James and I is that we were police officers and there was not really a place where you saw police officers with that voice. It was the two of us.” (Our full conversation is online at You Decide, my podcast).

“You would not outwork James Davis during campaigning,” said Adams. “He would be on the corner, buy a little child a popsicle, and say, ‘Go home and tell your mom I bought you that popsicle.’”

When the council seat opened up in 2001 due to term limits, I decided I’d had my fill of life as a candidate and went to law school. Davis beat a crowded field and carried the anti-violence message into the Council, pushing for gun control measures and funding for groups aiming to turn young people away from gangs and guns.

Davis had only served in office for a year and a half when a young new rival named Othniel Askew popped up. He told a lot of people a lot of different things, claiming to be an Air Force veteran (true), a real estate developer (possibly), an orthodox Jew (nope), and a graduate of Yale Law School (false). When Askew began circulating nominating petitions, Davis befriended his challenger, talked him out of running, and told the rest of us that he’d brought the young man into his camp and might offer him a job. The rumor was that Davis had quietly threatened to out Askew, who was known to frequent gay clubs, which likely would have triggered a backlash from the district’s sizable bloc of conservative Hasidic voters.

I remember the three of us driving around the city one night, talking about politics and the upcoming primaries. Davis was comfortable enough that he fell asleep along the way. Askew seemed strange, but you could say that about a lot of people in Brooklyn.

A few days after that trip, all hell broke loose inside the City Council chambers.

“I was walking up the inner passageway and I had literally just put my hand on the door handle and I heard gunshots,” recalls State Senator James Sanders, a councilman at the time. “I am a Marine and my mind immediately said ‘large caliber pistol’. So I froze at the door, trying to figure out what to do. And then I heard return fire.”

Askew had snuck a pistol into the building and shot Davis at point blank range while the two men were in the upstairs visitor’s gallery. Richard Burt, a member of the City Hall security detail, immediately fired up into the gallery, hitting Askew four times and killing him on the spot.

Other officers herded members into a room and guarded Mayor Mike Bloomberg, who was sitting at his desk on the west side of the building, not far from the mayhem. “Mayor Bloomberg came out and he was kind of matter of fact. I do remember him saying this much we know is true: Councilman James Davis is dead,” Todd-Medina told me. “I remember I was standing next to then-Councilwoman Yvette Clarke, who just started bawling. She put her head on my shoulder. She was crying. We were just trying to take it in.”

The assassination remains the first and only killing inside City Hall, and security today is much tighter. The youngsters who were breaking into Brooklyn politics a generation ago are now the establishment, including Mayor Adams and Tish James, who won the seat vacated by Davis and began the climb to her current position as state Attorney General. Clarke is in Congress now, and so is Jeffries, who leads the House Democratic Caucus and is on track to become Speaker of the House.

A post office and a cultural center in the district are named after Davis. Those of us who remember his energy, his wisecracks and his bold, earnest attack on community violence will occasionally tear up when we pass those places, holding our friend in memory like the line in the old pop song “Forever Young”: Youth’s like diamonds in the sun / And diamonds are forever.

More of the City Politic

- New York City’s Next Mayor Needs You

- How Desperate Will Eric Adams Become to Woo Trump and Get a Pardon?

- Finding Jordan Neely