Harlem politics, like the famous talent competitions onstage at the Apollo Theater, can be tough, unforgiving, and, occasionally, a place where stars are born. That’s what happened in late June when Yusef Salaam, a first-time candidate for office, handily beat two fixtures in uptown politics, Assemblymembers Inez Dickens and Al Taylor, with an impressive 63 percent of the vote after a ranked-choice calculation. His party’s nomination is virtually tantamount to a general-election victory in the overwhelmingly Democratic district, and Salaam is widely expected to win in November and take office in January.

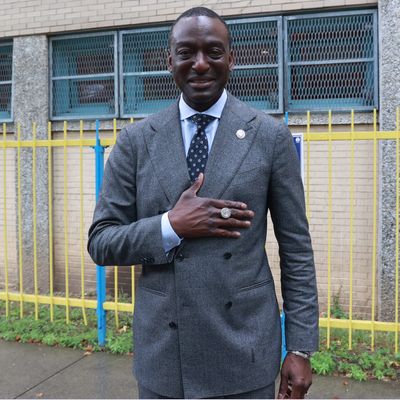

His surprise victory signals the arrival of a homegrown leader with quick wits, confidence, personal charisma, and a story that has resonated deeply for decades in the capital of Black America.

“The fact that this was 33, 34 years in the making really did a lot,” Salaam told me after his primary win. “People knew my story.”

And what a story it is. Salaam was one of five Harlem teens rounded up and railroaded in April 1989, falsely accused of beating and raping a white woman, Trisha Meili, in Central Park. The subsequent convictions of Salaam, Antron McCray, Korey Wise, Kevin Richardson, and Raymond Santana were, in legal terms, a disgraceful miscarriage of justice: High-pressure, hours-long interrogations yielded confused, conflicting videotaped confessions in which none of the teens could accurately describe the time and location of the attack or the victim’s clothing. The boys almost immediately recanted the coerced confessions, and their lawyers futilely pointed out that there were no eyewitnesses or physical evidence (none of the boys’ DNA matched a sample taken from Meili’s rape kit). That didn’t stop Salaam and the others from being convicted and serving between six and 13 years in prison.

The atmosphere at the time was wild and raw with public fury trained on the five teenagers as symbols of the city’s crime rate, which was soaring toward an all-time high of 2,245 murders that would be reached the following year. A local businessman, Donald Trump, famously went so far as to buy full-page ads in the city’s four daily newspapers calling for New York to reinstate the death penalty.

Salaam and his co-defendants were exonerated in 2002 after a convicted rapist named Matias Reyes voluntarily confessed to the crime and a DNA test showed a match. The city ultimately paid a $41 million settlement to the five men in 2014. Salaam, by then raising a family in Atlanta, had become a motivational speaker on criminal justice and other matters.

That could have been the end of the agonizing tale. But Keith Wright, a lifelong Harlemite, an ex-assemblyman, and a chairman of the Manhattan Democratic Party, contacted Salaam in Atlanta and recruited him to run for the City Council seat in Central Harlem held by the freshman member Kristin Richardson Jordan, who soon announced she would drop out of the race.

“I had been toying around with the idea of politics for a while. Keith came and said, ‘You know, you would be great at this.’ He said, ‘You’re like our Nelson Mandela,’” Salaam told me. “I knew I had to come back to the scene of the crime.”

Wright’s son Jordan ran the campaign, which benefited from the multiple documentary accounts of the case that had seared the injustice into local memory. A narrative of return and redemption quickly took hold: Back in 1989, one of Salaam’s early defenders was Bill Perkins, leader of the tenants association at Schomburg Plaza where he and Salaam lived; Perkins went on to serve for more than a decade in the council seat Salaam was running for.

On the campaign trail and in a televised debate, all three candidates in the race agreed on the basics, promising to fight for more jobs for local residents and to seek a new location for a planned legal cannabis dispensary scheduled to open on 125th Street. All three vowed to try to restart negotiations with a developer to build 916 new apartments on 145th Street, a project that collapsed in controversy last year when Councilwoman Jordan demanded deeper levels of rent subsidy than the builder was willing to provide.

But make no mistake about it: Salaam won not because of his proposed ideas on siting weed dispensaries and setting housing-subsidy levels. His election was Harlem’s embrace of a prodigal son and survivor of racial injustice.

“The incident with the Exonerated 5 happened 35 years ago, and a lot of people in Harlem never forgot the ugliness and the indignity at the way those boys were treated,” former governor David Paterson told me on Primary Night, as the early returns made clear Salaam was likely to win. “I think maybe just the resentment that a lot of people in Harlem and a lot of people around the city feel about that is presenting itself tonight.”

Elinor Tatum, publisher and editor-in-chief of the Harlem-based Amsterdam News who was around the same age as Salaam when the case broke, agreed. “Here’s a young man that so many years ago was thrown away by so many people. The Amsterdam News, however, was not one of them,” she told me, referring to her father and predecessor at the paper, Wilbert Tatum, who made the controversial decision to print Meili’s name on the theory that it was unfair to publish the names and faces of juvenile defendants while shielding the name of their alleged victim and accuser.

“We believed in all of them, and we said from the onset that these young men did not do it,” Tatum told me. “This election, for him, was another day of reckoning. This was another exoneration.”