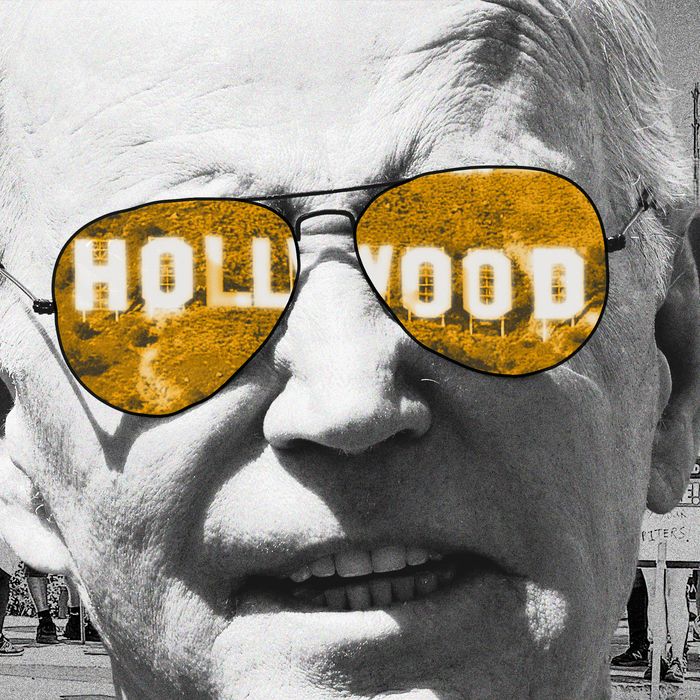

Just two weeks after announcing his 2020 presidential bid, Joe Biden traveled to Los Angeles and personally asked the Hollywood elite to help fund his campaign to beat Donald Trump. In the front yard of ex-HBO executive James Costos’s Brentwood home, Biden was fêted by a crowd of 300 who’d been gathered by some of the entertainment business’ highest-flying dealmakers, including Jeffrey Katzenberg (the ex-Disney chairman and DreamWorks Animation founder), Chris Silbermann (then the boss of the ICM agency), Peter Chernin (the ex-Fox film and broadcasting honcho), and Tom Rothman (CEO of Sony’s film group). With everyone there hitting the legal maximum for donations, it took Biden just a few hours to bring in $750,000.

Four years later, the president is on the cash trail again, preparing for a likely rematch against Trump. He’s already hit Manhattan, the Bay Area, and Chicago, plus destinations as far-flung as Freeport, Maine, and Albuquerque, New Mexico — but not Los Angeles. The liberal goldmine of Southern California that’s pumped millions into Democratic campaigns for decades has been missing from his itinerary — declared off-limits ever since Hollywood’s writers and actors went on strike against the people who run the town, some of whom also happen to be among Biden’s biggest donors.

The decision — which has only been whispered about, never formally communicated — is the result of a calculation by Biden’s campaign that the president can’t risk raising money in person from the very people the strikes are aimed at, folks like Disney’s Bob Iger, Netflix’s Reed Hastings, and Sony’s Rothman, especially since Biden’s been so open about supporting the walkouts. As a result, with a billion-dollar presidential campaign already here and no sign that the strike will resolve soon, some of the Democratic Party’s heaviest financial hitters, and some of its most prominent celebrity surrogates, are on the political sidelines.

It didn’t take long for Biden and his advisors to reach a consensus on what to do about Hollywood’s money once the strikes began this spring. With the president leaning heavily on his support from organized labor in his re-election campaign and standing prominently with the strikers as part of that posture, there was no way “Union Joe” could hazard being seen as sympathetic to the studios, no matter how obvious it was that he needs the money.

One reason the situation is so uncomfortable is the fact that Katzenberg, the legendary former studio exec with a massive Hollywood network, is one of his campaign’s two co-chairs — who Biden can’t visit in L.A. “It would be awkward to go because of Katzenberg, in particular,” explained one sympathetic Democrat wired into the reelection fundraising gameplan. He may not be a current studio head, but, “If you do anything with the Katzenberg brand, it’s problematic.”

So publicly, at least, Biden has opted to keep his distance. This extends only as far as the president’s in-person trips to California though, which is where a huge chunk of campaign cash usually comes from. Katzenberg has instead come to Biden: He left L.A. for fundraisers in Chicago and New York, and in those expensive rooms, Biden has praised him: “I have a lot of assets in my campaign, but none more consequential than Jeffrey Katzenberg,” the president said in late June at a small, private midtown Manhattan event where the mogul was seated near Governor Kathy Hochul. And last week, Katzenberg was part of a small group of Biden’s leading fundraisers and supporters who met for a six-hour check-in. The what-to-do-about-L.A. question came up in a broader chat about facilitating strategy, scheduling, and messaging before the summer lull ends and the fall cash rush begins. But the short-term answer was to wait.

Ultimately, major Hollywood figures on both sides of the strike are not just supportive of Biden but looped into his broader political operation. “The Katzenbergs of the world are deeply embedded into the culture of the administration right now, but so is a lot of Hollywood that’s not studio heads,” says one senior national-level union official. Prominent executives like Iger and Hastings are well-known party donors and have had presidents’ ears in the past, which is also true for director-slash-production honchos like Steven Spielberg and J.J. Abrams. Along with their spouses, this group donated millions to pro-Biden efforts in 2020 and helped raise even more. (Spielberg’s company just laid off a fifth of its staff after making a new deal with Universal; Abrams has publicly donated to a strike relief fund.) Bryan Lourd runs the mega-talent agency CAA, which is representing actors on strike; he recently popped up at a picket line outside 30 Rock and often speaks to Kamala Harris, who frequently returns to her home in L.A. George Clooney, also on strike, has been known to occasionally offer messaging advice to both the president and vice president. Many more actors played a prominent role in boosting Biden’s last campaign when he was unable to travel amid the pandemic and celebrities were called upon to promote him to their massive followings.

The good news for Biden in the short term is that he’s hardly facing a cash crunch after his campaign, and the Democratic National Committee brought in $72 million last quarter. It also helps that the studio chiefs who are close to the White House have made it clear to the Democrats running Biden’s political operation that they get his conundrum. Plenty of them are, for now, content to avoid the publicity headache that inevitably comes with a big donation or a visit from the president. “Donors here don’t really want to be put in the position of writing large checks while their companies are saying, ‘We don’t have the money to make a deal with the unions,’” says one elite-level L.A. fundraiser. In the meantime, some of the most politically active Hollywood superplayers figured that their checks wouldn’t draw as many headlines without an in-person Biden visit and sent him money anyway. Katzenberg and Hastings have donated, respectively, hundreds of thousands of dollars to Biden since he launched his campaign this spring. (Katzenberg’s cash arrived when the strikes were just a threat; Hastings donated after the writers had set up shop outside the studios.)

But the big West Coast cash dump has yet to land, and no one close to Bidenworld thinks it can wait forever. If they’re not sweating yet, they may start soon, even the most sanguine of the bunch acknowledge. Presidential fundraising is not usually a game of patience, and the coming campaign is likely to cost Democrats over a billion dollars. Even in the short term, big-money trips can help campaigns project strength by giving them significant cash boosts all at once.

So while the national political operation and L.A. fundraising circles both outwardly preach calm, their innermost circles are considering their options. It now seems clear that Beverly Hills is highly unlikely to make it onto Biden’s itinerary for fundraising trips tentatively planned for the end of the summer and early fall, a handful of senior Democrats say. Instead, other groups of donors are getting earlier calls than usual. “We look at markets, and if we’re not doing L.A. in September, what are we adding? Is it Seattle? Bay Area, Chicago, New York again? Philadelphia? The numbers don’t change in terms of targets and where we want to be in Q3 and Q4,” says a high-level operative who has been in on those discussions.

But those discussions have also been coming around to the reality that Biden needs Hollywood bucks eventually and that the prohibition on an L.A. stop is also costing him non-entertainment business money in the region. Does either Orange County or San Diego, the senior Democrat mused, qualify as “far enough away” from L.A. for Biden to visit and scoop up local donations and avoid angering all of Hollywood? The preliminary conclusion is “probably.”

Then there’s always the quieter option: Having surrogates do the in-person work while the headline-driving president stays away. In mid-June, with the writers striking and the actors threatening to join in, Jill Biden stopped by L.A. for a little-noticed fundraiser of her own. The event was hosted by prominent lawyers, not entertainment business moguls, and the first lady spoke only briefly to the crowd of 80. She didn’t mention the strike at all, just her husband’s work and the threat of MAGA Republicans. The Hollywood sign was visible in the hills behind her.