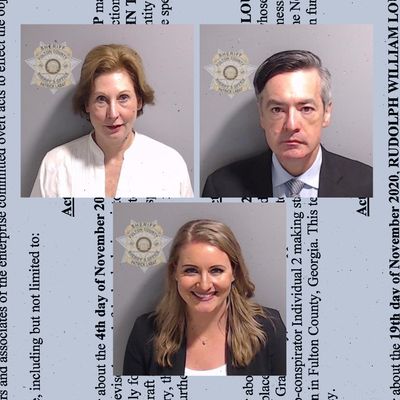

A surprising new source for the country’s biggest legal news emerged over the past week: the YouTube channel of Judge Scott McAfee in Fulton County, Georgia. On Tuesday morning, the judge went live to make national news yet again, this time with the guilty plea of Jenna Ellis, a Trump 2020 campaign lawyer who was among the 19 defendants charged in District Attorney Fani Willis’s RICO case against the former president.

Ellis’s deal is the latest in a succession of recent plea agreements, which in turn have generated some familiar responses. Donald Trump’s lawyers claim these deals are practically meaningless and expose the weakness of Willis’s case, while Trump’s most persistent antagonists in the media have argued that the deals are terrible news for Trump — that the walls are closing in, the shoes are finally dropping, and so on.

In this case, the dispute is actually more interesting than usual, since there is something to both sides. The plea deals are in fact bad news for Trump, though not nearly as bad as they could have been, and in large part for reasons that are more subtle than the prevailing narrative suggests.

A Slap on the Wrist

Ellis is the fourth defendant to plead guilty in Willis’s case following guilty pleas last week from Sidney Powell, Kenneth Chesebro, and, last month, a bail bondsman named Scott Hall.

There are two critical facts about the plea deals: First, none of these defendants was forced to plead guilty to the alleged RICO conspiracy, the “top count” in the case. Second, none will do any prison time.

Ellis, for instance, pleaded guilty to one count of aiding and abetting false writings and statements, apparently in connection with false claims of voter fraud she had made in testimony before the Georgia state legislature. Chesebro pleaded guilty to one count of conspiring to file false documents, apparently in relation to the use of alternate (or “fake”) Trump electors in the state. Both Powell and Hall pleaded guilty to multiple counts of conspiring to commit intentional interference with the performance of election duties, apparently in connection with a breach of state voting systems that was supposed to turn up evidence of fraud.

Under the terms of their deals, they all received either five or six years of probation and had to pay a fine. They also have to testify in future trials if asked to do so by prosecutors, though Hall’s lawyer has already publicly said his client has little to offer to the broader case.

The Bad News for Trump

Pretty much any time a defendant pleads out in a large, multi-defendant case, that is bad news for the lead defendant and the prosecutors’ main target — who, in this case, is undeniably Trump.

One common metaphor used to describe how prosecutors work in complex cases is that of building a brick wall. Prosecutors are not looking to present a single conclusive or explosive piece of evidence to the jury that will compel it to find the defendants guilty. They are trying to build a case slowly and methodically with small pieces of evidence — brick by brick — in the hopes that, in the end, the jury will see a solid, insurmountable wall of evidence and testimony that establishes the defendants’ guilt.

The plea deals give Willis and her prosecutors more bricks to use against Trump at trial. How significant they will ultimately prove to be is a separate matter (more on that below), but the much bigger downside for Trump, at least at the moment, is that Powell and Chesebro were about to go to trial and their plea deals scuttled that plan.

Had it gone forward, the trial would have provided Trump and his other co-defendants with a major strategic benefit for their own defenses. Fulton County prosecutors had publicly said they intended to present the same witnesses and evidence at the Powell-Chesebro trial as they would in a larger one involving all of the defendants. They had planned to call more than 150 witnesses over the course of a four-month trial.

That meant that Trump’s lawyers would have gotten to see all of the evidence against him in exhaustive detail, would have been able to identify potential gaps or weaknesses in the evidence that are not readily identifiable in discovery, would have had a complete record of witness statements that could later be used to impeach people in a subsequent trial if their testimony varied in any meaningful way, and, more generally, could have strengthened their legal arguments by seeing how things played out in the first trial. They could even have taken video from the trial to use in jury studies as part of Trump’s defense in Georgia and in the parallel election-subversion case brought by federal prosecutors in Washington, D.C.

There is no question that Willis’s team knew all of this too. That is presumably one reason they aggressively fought the prospect of separate trials in the first place. It also likely had a lot to do with their decision to enter into plea deals with Powell and Chesebro on the eve of their trial.

The Not-So-Bad News for Trump

If you charge a major multi-defendant criminal conspiracy, you don’t want just random plea deals.

Ideally, you want defendants to plead to the charged criminal conspiracy itself. That way, if they take the stand and testify as witnesses in the main trial, they are endorsing the central factual contention in the case — that there was in fact a sprawling, multi-defendant conspiracy involving Trump — and tacitly endorsing the underlying legal theory in the prosecution (that the conduct was not just bad but a violation of state RICO law). State prosecutors often work differently from federal ones (among other reasons, they are generally far more resource constrained), but it is safe to say that many federal prosecutors would have insisted on a guilty plea to the top count as part of any deal with Trump’s co-defendants in a case like this.

In each of the deals so far, however, the defendants have pleaded guilty to misconduct concerning fairly narrow elements of the indictment in factual terms and in certain cases to conduct with no clear connection to Trump himself. Powell and Hall, for instance, pleaded guilty in connection with a breach of Georgia election systems, but there is no indication that Trump himself had much, if any, meaningful involvement in that effort. By the same token, there is no indication that the plea deals do anything to strengthen the DA’s case in some key areas for Trump’s criminal exposure, such as his infamous call to Georgia secretary of State Brad Raffensperger.

It will be interesting to see whether — or perhaps when — this starts to change. Early plea deals in big cases tend to be the most generous because prosecutors want to incentivize people to come in and cooperate. To use another common prosecutorial metaphor, you are hoping that, like falling dominoes, plea deals generate more plea deals.

At some point, however, prosecutors should want to extract more serious concessions in these deals, both in terms of the substantive charges being pleaded out and the possibility of actual prison time, as opposed simply to probation and a few thousand dollars in fines.

There is also some chance that Powell, Chesebro, and Ellis could provide prosecutors with more damning evidence on Trump than their plea deals publicly indicate, particularly relating to private meetings with the former president. But some caution is in order. Remember George Papadopoulos? When he pleaded guilty in late 2017 as part of Robert Mueller’s Trump-Russia investigation, many believed it might be the start of a cascade of devastating developments for Trump that would ultimately culminate in his prosecution, his impeachment, or both. Things did not turn out that way, to put it mildly.

To be clear, this is not the same situation. This time around, six years later, Trump has actually been criminally charged and we have a coherent road map to the Fulton County DA’s case in the form of the office’s indictment. It is much easier to assess real-time developments in a charged case than in a case in its investigative stages, but a broader principle still applies: It is best to try to take things as they are, or as they appear to be at the moment, and not as we may want them to be.

Like it or not, Trump has viable defenses to this prosecution — for instance, that prosecutors cannot establish that the overarching alleged conspiracy actually existed, that they cannot prove Trump knowingly entered into it, and that the conspiracy (even if it did exist) was not sufficiently organized or even long enough in duration to qualify as a RICO conspiracy. From the outside looking in, those defenses appear to remain intact despite the plea deals, essentially as viable today as they were a couple of weeks ago.

That may very well change at some point. Trump’s lawyers have to be concerned about the prospect themselves, public bravado notwithstanding, but the biggest recent setback for them is not what has happened in the way of these recent plea deals. It’s what just didn’t happen: a trial that would have given Trump and his lawyers a free and comprehensive preview of the case against the former president.