It is unfortunately true that many younger Americans, if they’ve at all heard of Vernon Jordan — who died yesterday evening at 85 — it was probably as a big-time Friend of Bill, the 42nd president’s confidant and golfing buddy. In truth, in Jordan’s long life, his relationship with Bill Clinton was more a reflection of his long climb to the summit of American political life from his marginalized upbringing than any sort of end in itself. Clinton, who had known Jordan since the 1970s, consulted him over the years just as hundreds of other wisdom seekers had.

Jordan grew up in Jim Crow Georgia, the son of a postal-worker father and a mother who built a catering business. While waiting tables at the events she catered, he had a good chance to observe Atlanta’s white elite, and he began a habit of circulating easily in both Black and white worlds. He attended the virtually all-white DePauw University in Indiana before completing his education at Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C., putting him in close proximity to the movers and shakers of the civil-rights movement. Then, as a law clerk for an Atlanta attorney, he was deeply involved in the lawsuit that forced the desegregation of the University of Georgia. His formal involvement in broader civil-rights activity was succinctly described in his New York Times obituary:

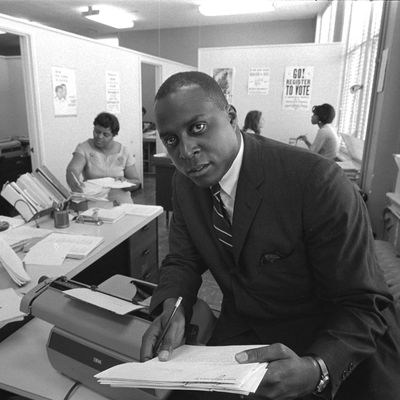

After the Georgia case, he served as Georgia field director of the N.A.A.C.P. The job required him to travel regularly throughout the Southeast to oversee civil rights cases both large and small. He said he tried to model himself after a friend, the vaunted director of the Mississippi office, Medgar Evers, who was later assassinated.

In short order he became director of the Voter Education Project of the Southern Regional Council and was named executive director of the United Negro College Fund in 1970. A year later his friend Whitney Young, the head of the Urban League, drowned on a trip to Lagos, Nigeria, and Mr. Jordan was recruited to fill the unexpected vacancy.

The Urban League occupied a special niche in the civil-rights movement as a representative of high-level business interests, including not a few run by Republicans. So at a relatively early age, Jordan began to exhibit his signature commitment to activism as it could be advanced through insider influence. It was in some ways an ideal spot for him, as the Washington Post observed:

He oversaw a budget of $100 million and traveled extensively to raise money from corporate leaders to support job training, early-childhood education and other programs aimed at improving Black life in the United States. He joined the boards of blue-chip companies including American Express, Xerox, Dow Jones & Co., Union Carbide and RJR Nabisco, and used his access to executives to encourage major companies to hire women and members of minority groups.

But Jordan wouldn’t escape the tribulations suffered by other civil-rights leaders. In 1980, a white supremacist who was enraged at seeing Jordan in the company of a white woman (a member of the Urban League’s board, as it happens) while visiting Fort Wayne, Indiana, shot him in the back and nearly killed him. Then-president and fellow Georgian Jimmy Carter visited Jordan in the hospital. After fully recovering, he was soon recruited by the former Democratic National Committee chairman Bob Strauss to join the premier Washington power firm of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, which became his perch (along with a variety of corporate boards and investment-firm associations) in the Beltway as he continued his civil-rights advocacy work.

By the time his old friend Clinton (to whom he had been introduced during 1970s civil-rights activities; he had met Hillary Clinton earlier, in 1969) ran for president, Jordan was perfectly positioned to serve as a trusted guide to his various circles of influence. He could have definitely had an ambassadorship had he wanted one, and Clinton reportedly offered him the attorney-general post. But Jordan preferred to stay in the background as a sort of continuing legend, known for charm, discretion, and the “ability and capacity to pick up the telephone almost anytime and call almost any member of Congress,” as John Lewis said in 1992. Characteristically, he never had anything to say in public about his minor role in the Monica Lewinsky scandal, which nearly took Clinton down (Jordan had allegedly helped arrange for Lewinsky’s employment), and after frequent testimony in legal proceedings connected with the saga, he was never charged with any wrongdoing.

He eventually became close to Barack Obama and told an interviewer that he had wept when watching him declared the winner of the presidency in 2008 — even though he had also told the future 44th president, even before he became a candidate, that his loyalty to the Clintons dictated that he would back HRC. Both sentiments were characteristic.

Jordan never lost his influence or the wide circle of friends who helped sustain it. If only because of his background and unlikely career, we may never see his like again.