If your only source of information about American politics in 2018 were the GOP’s campaign ads, you would think that the Democratic Party was a radical left-wing organization, whose principal constituents were anarchists, misandrists, literal terrorists, and acolytes of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. If you supplemented those 30-second spots with Donald Trump’s stump speeches, and Fox News’ prime-time lineup, you might further conclude that Nancy Pelosi was the chair of The House Antifa Caucus (which roams the National Mall after dark, their masked faces lit only by the glow of burning flags); Dianne Feinstein was the lead sponsor of the MS-13 IS THE LANGUAGE OF THE UNHEARD ACT; and Chuck Schumer regularly delivers tearful filibusters, in which he memorializes the victims of American imperialism, recites the SCUM Manifesto from memory, and apologizes for the ineradicable sin of his whiteness.

In other words: The GOP’s message-makers are working round-the-clock to collapse the distinctions between the Democratic Party and the most radical activists at the far-left fringes of its big tent (while also, of course, caricaturing the latter). And it isn’t hard to understand why they’ve pursued this gambit: The GOP’s donor-driven governing agenda is deeply unpopular, and thus, the party’s primary source of mass appeal is traditionalist, white America’s fear and loathing of the radical left, and the alienating demographic and cultural changes that they’re supposedly fomenting.

The actually existing Democratic Party might be a compelling villain to conservative activists who believe that legal abortion is genocide, and that the welfare state is tyranny. But rank-and-file Republicans think that universal background checks are a good idea, don’t want Roe v. Wade overturned, support an immigration compromise that combines a path to legal status for law-abiding undocumented residents of the U.S. with increased border security, and want the federal government to spend more on ensuring universal access to affordable health care. If such voters understood that Joe Manchin has more influence over the Democratic Party than Colin Kaepernick or Saul Alinsky, they’d have little reason to turn out for Republicans this November.

Fortunately for the GOP, many centrist pundits share their base’s misconceptions about Team Blue, and, as a result, mindlessly translate Republican propaganda into conventional wisdom.

True, commentators like the Washington Post’s Charles Lane do not think that antifa runs the Democratic Party — but Lane does write that “progressive ideologues” dominate it in a recent column. And while the New York Times’ David Brooks wouldn’t mistake Chuck Schumer’s caucus for a Leninist vanguard, he has, ostensibly, mistaken it for an “extreme cult.”

Lane and Brooks offered those assessments of the Democrats this week, after each perused the same study of political attitudes in the United States. Said study, which was released by More in Common, a nonprofit dedicated to combating political polarization, found that American voters actually have more in common than our political discourse tends to suggest. In fact, the report argues that the appearance of an irreconcilable red-blue divide is driven by tiny — but loud — minorities on both the far right and far left. In More in Common’s typology of the electorate, about 8 percent of American voters consistently espouse extreme left-wing attitudes, while 6 percent consistently voice extreme right-wing ones. The report dubs these two tribes “Progressive Activists” and “Devout Conservatives,” and notes that, for all their ideological differences, the two groups have many demographic similarities: Both are whiter, wealthier, better educated, and more politically active than the average American.

These extremists exert disproportionate influence over our politics, leaving an “Exhausted Majority” alienated from their government, and starving for compromise. As Brooks explains:

The good news is that once you get outside these two elite groups you find a lot more independent thinking and flexibility. This is not a 50-50 nation. It only appears that way when disenchanted voters are forced to choose between the two extreme cults. [my emphasis]

Roughly two-thirds of Americans, across four political types, fall into what the authors call “the exhausted majority.” Sixty-one percent say people they agree with need to listen and compromise more. Eighty percent say political correctness is a problem, and 82 percent say the same about hate speech.

There’s some cause for skepticism about these findings. To state the obvious, More in Common was never going to release a study showing that Americans have very little in common. And this bias shows up in some aspects of its survey design — most conspicuously, in the authors’ decision not to define “political correctness” for their respondents. A supermajority of the American public would (almost certainly) agree that “special interests” have too much influence over the federal government. But that unanimity would disappear the moment one started naming specific interest groups (say “Evangelical Christians” or “environmentalists”). Similarly, while 80 percent of Americans might abhor “political correctness,” the Exhausted Majority would likely splinter when asked whether that oppressive phenomenon keeps politicians from telling the “truth” about, say, the violent nature of Islam.

That said, the report’s broader argument — that the American public is much less polarized than the American elite — is consistent with a large body of political-science literature. And there’s certainly some value in remembering that the loudest partisans in your Twitter feed aren’t necessarily the most representative.

But if the More in Common study is somewhat edifying, the centrist commentariot’s repackaging of it is not. The problem with the latter is simple: Centrist pundits falsely presume that Progressive Activists enjoy the same hegemonic control over the Democratic Party that Devout Conservatives command over the GOP. And this leads them to erroneously suggest that the “Exhausted Majority” has no political home in the existing two-party system. As Mike Allen and Jim VandeHei instruct their savvy readership:

Be smart … Good news for third-party dreamers: Two-thirds of Americans (the study’s “Exhausted Majority”) have had it with this white fight — and yearn for something new.

As an upper-middle-class white left-winger — who believes the conservative movement poses a threat to both American democracy and humanity’s medium-term survival — I would love it if the Democratic Party were slavishly beholden to my “extreme cult.” But it isn’t.

Now, it’s true that the left’s influence over the Donkey Party is growing. Progressives are overrepresented among both Democratic primary voters and the party’s rising intellectual class. For these reasons, most of the party’s 2020 hopefuls have embraced a wide range of social-democratic reforms, and policies for redressing race and gender-based disadvantage. We are, indeed, a long way from the “Third Way.”

But even the most progressive elements within the congressional Democratic Party don’t take marching orders from the PC police. If you’re an “exhausted” American who despises Trump’s demagoguery — but also disapproves of protesters shutting down conservative speech on campus, or shouting at Trump administration officials at restaurants, or imposing their politically correct vocabulary on everyone else — then you might be Bernie Sanders!

Furthermore, the left-wing ideas that progressive Democrats do endorse — like, say, that the government should provide universal health care, establish tuition-free college, and give workers a voice on large corporate boards — are neither extreme in relation to median public opinion in the U.S. nor when compared to the policy regimes in other advanced democracies.

That said, even if we (baselessly) stipulate that the “Exhausted Majority” longs for policies that are more conservative than Elizabeth Warren’s, but more liberal than Mitch McConnell’s, such voters would still be well represented by the Democratic Party.

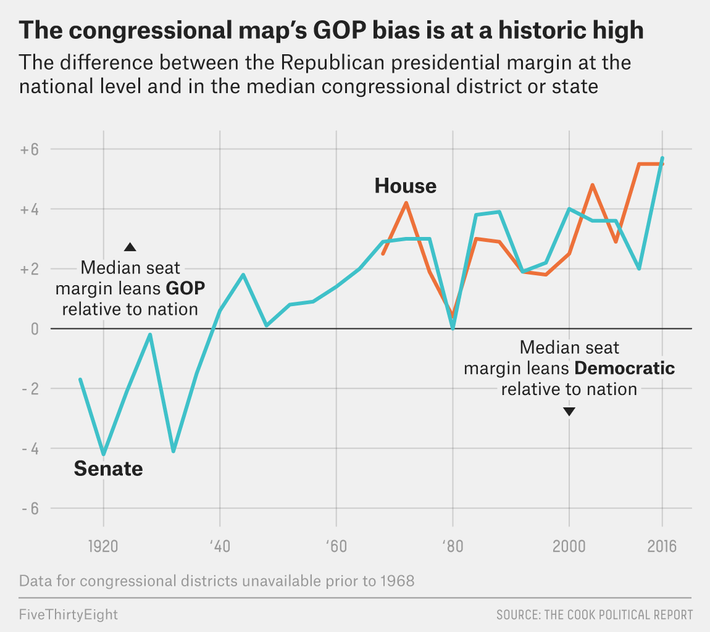

On the Republican side of the aisle, ideological conservatives — and corporations whose policy preferences lie far to the right of the general public’s — provide the GOP with virtually all of its campaign donations and the lion’s share of its think-tank funding. With the aid of such donors, the GOP’s far-right faction routinely defeats (perceived) moderates in primaries. And the biases of America’s congressional map, which gives disproportionate voice to predominantly white, rural areas of the country, inflates the clout of the party’s most extreme forces.

The Democratic Party’s “ideological extremists” do battle on far less hospitable terrain. While Devout Conservatives are at odds with corporate America on a handful of the latter’s secondary issues — like immigration and LGBT rights — they are pulling in the same direction on just about everything else. Progressives, by contrast, are forever trying to override their party’s corporate wing on its bottom-line concerns (taxes, regulations, and labor policy). And that’s not easy, when Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Big Pharma are among the Democratic Party’s largest shareholders. Meanwhile, the left still hasn’t done much to put the fear of primary challenges into moderate Democratic incumbents — who aren’t white men representing diverse, deep-blue districts. The triumphs of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley notwithstanding, the “tea party of the left” has thus far proven far less potent an electoral force than the original brand.

One possible cause of this asymmetry is the aforementioned bias of the congressional map: Thanks to Republican gerrymandering and the Senate’s malapportionment, right-leaning voters punch well above their weight in American elections. It’s possible that this year’s “blue wave” will allow Democrats to overcome this disadvantage, and put the party in a position to claim majorities in both chambers by 2020. But even if they are so fortunate, their legislative majorities will live and die on the whims of senators like Joe Manchin, Jon Tester, and Joe Donnelly (whose latest campaign ad is a declaration of war against Progressive Activists) — along with those of a wide array of House members who were elected on the strength of their support from college-educated white women with centrist sensibilities. At present, Nancy Pelosi’s caucus is already home to 18 “Blue Dog Democrats” (a faction of moderate lawmakers who derive their name from the sentiment that liberal ideologues have “choked them blue”)

and the 68 self-professed “pro-business” lawmakers of the “New Democrat Coalition.”

Which is to say: Even if Democrats elect Bernie Sanders president in 2020, the party’s governing agenda will almost certainly end up being center-left by the Exhausted Majority’s standards; or center-right, by Canada’s.

I personally do not want the Democrats to be a party that David Brooks could comfortably support, if his personal brand didn’t require him to do otherwise. And I don’t think that it has to be, at least not indefinitely. The rise of small-dollar, online donor armies — and idiosyncratic, class-traitor billionaires — is already mitigating the Democrats’ reliance on corporate cash. When and if the millennial generation begins turning out in large numbers, and the left’s myriad social movements gain sufficient scale and organization, progressives will have a fighting chance to consolidate power in the Democratic Party.

But for now, the actually existing Democratic Party is a centrist organization that champions fiscal responsibility, balanced budgets, procedural norms, a civil public discourse, strong border enforcement, a globe-spanning military empire — and, like the vast majority of the American people, a more ambitious and generous social-welfare state, higher taxes on the rich, abortion rights, a path to legal status for the undocumented, more regulatory protections for consumers and the environment, and various incremental reforms aimed at increasing labor’s share of economic growth.

The actually existing Republican Party, on the other hand, is an extreme, reactionary formation that champions procedural radicalism, nativism, voter suppression, far-right militia movements, the stigmatization of the Islamic faith, sheriffs who habitually violate the law and their constituents’ civil rights, the subordination of federal law enforcement to Donald Trump’s whims — and, unlike the vast majority of Americans, a smaller and less generous social-welfare state, lower taxes for the rich, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, fewer regulatory protections for consumers and the environment, and various reforms aimed increasing Wyatt Koch’s share of economic growth.

When the (unfortunately existing) centrist commentariat elides these distinctions — and wishes a pox on both “extreme cults” — they are helping the most ideologically extreme major party in the developed world blind the American people to how much they have in common.