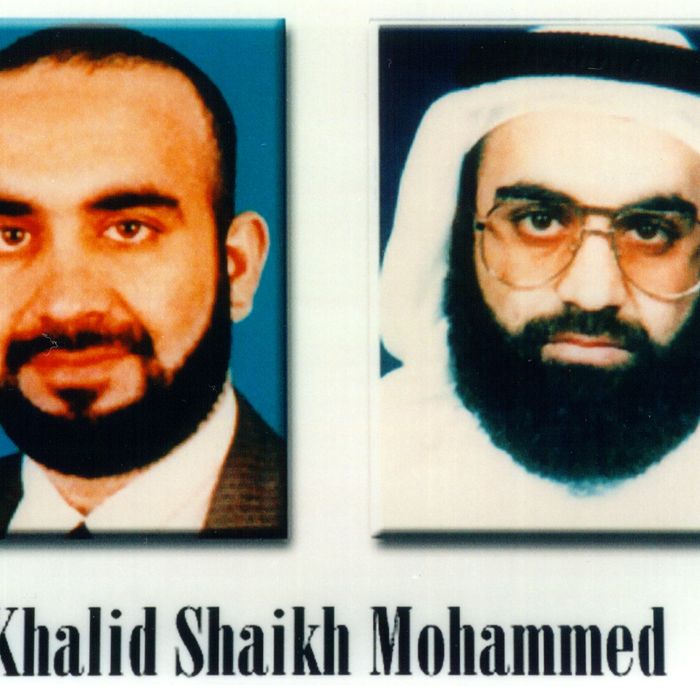

Terry McDermott, a veteran journalist and the author of two books on the men who carried out the 9/11 attacks, has spent years working on the third, about the quest to bring the plot’s mastermind to justice. “The original title was The Trial of KSM,” McDermott said last week, as he prepared to fly down to Guantánamo Bay to see Khalid Sheikh Mohammed appear in court. “Then I realized, Well, there ain’t going to be a trial. So it’s now called The Trials of KSM.”

The addition of that “s” evoked two decades of imprisonment without resolution. After KSM’s capture in Pakistan in 2003, he was whisked off to a secret CIA prison in Poland where he was waterboarded at least 183 times. Once he was deemed no longer useful as a source, he was transferred to Guantánamo where he and a handful of accomplices were supposed to be put on trial in front of a special military commission, which had the power to impose the death penalty. The process was supposed to offer streamlined justice, but it got bogged down by constitutional issues and hesitations about the use of evidence obtained through torture. But when McDermott spoke to me by phone on Thursday, it seemed the trials were finally coming to a conclusion. The U.S. government had reportedly agreed to a plea deal that would take the death penalty off the table in return for KSM’s full cooperation in a sort of fact-finding proceeding. The government would present its evidence and the terrorist would reportedly answer questions about how the plot was planned and carried out, some of them submitted by the family members of 9/11 victims. In essence, the terms of the trade were: life for facts.

“I’m not a big believer in catharsis,” McDermott said. “There will be more detail. That’s what we’ll have — more detail.”

Then, the following evening, the news broke that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin — who oversees Guantánamo and the military commission trial process — had scuttled the plea deal, at least for the time being. From the outside, the election-season backtrack looked bumbling, indecisive, and cravenly political — which would be pretty much in keeping with the way things have gone for the past two decades in KSM’s forever trial. In its own perverse way, perpetual limbo might represent a fitting punishment for a murderer who imagined he would meet a cinematic end. (According to the 9/11 Commission’s 2004 report on the attack, KSM told CIA interrogators he originally proposed hijacking ten planes, one of which he would have landed himself, in order to deliver a speech at the airport.) But the decision to pull the plea bargain is frustrating to at least one group of people: those who want to complete the historical record.

After all this time, what could KSM still tell us? It might be hard to imagine, after living with the attack’s consequences for a generation, that there is anything new to say about it. Besides a few wacko conspiracy theorists, no one questions what happened that day: 19 members of Al Qaeda boarded four planes, took them over by brute force, and flew them toward their targets, killing thousands. Afterward, the FBI mounted the largest investigation in its history, compiling an archive of millions of pages of evidence. The 9/11 Commission produced its seemingly definitive report. And there, the flow of information more or less stopped. Much of what the government knew remained classified. The FBI’s evidence remained off-limits to researchers for the most part so long as the 9/11 trial was pending. KSM and his accomplices disappeared into Guantánamo where their occasional appearances before the military tribunal were tightly controlled. In 2014, KSM’s court-appointed defense attorney revealed that the CIA, independent of the judge, was using a remote mute button to cut the audio feed of the proceedings to the spectator gallery whenever anyone strayed into sensitive areas.

A few years ago, for a history book I wrote, I attempted to reconstruct the plot from the moment four Arab men from Hamburg set off for Afghanistan, in November 1999, to the morning that three of them boarded the planes they would crash. (The surviving member of the group, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, is also imprisoned at Guantánamo but has been found mentally incompetent to stand trial as a result of his torture at the hands of the CIA.) I relied heavily on McDermott’s book Perfect Soldiers, a group biography of the Hamburg men, as well as his co-authored follow-up, The Hunt for KSM. During my research process, I was struck by how little we know about how the terrorists worked out the mechanics of the attack, which was successful on a scale no terrorist group has ever come close to replicating. (Thankfully.) “It was really clever, I’ll say that for it,” McDermott told me. And yet no one outside of the U.S. government has ever heard them describe how they pulled it off. Bin al-Shibh, who played a coordinating role, gave one gloating interview to an Al Jazeera reporter before he was captured. The only time we have ever heard the voice of Mohamed Atta, the operational leader of the attack, is on a recording of a few stern announcements he made that morning to his doomed passengers, which he inadvertently transmitted back to air-traffic control.

By all accounts, KSM is proud of what he accomplished in the “planes operation,” and he has readily confessed to his role in it as well as numerous other crimes, including the beheading of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl. But the details of his confessions have been filtered and, one suspects, selectively deployed for public consumption. The 9/11 Commission’s report relied on CIA-provided summaries of KSM’s torture-tainted interrogation sessions. (Which kind of makes you wonder about that story about that even more spectacular ten-plane attack.) They were similarly compiled into the closest thing to a KSM confession that has ever been made public, a 58-page affidavit presented at the 2006 trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, the alleged “20th hijacker.” (The document stated that, although the witness was “unavailable to testify … for national-security reasons,” it was a fair summary of his “oral statements made in response to extensive questioning.”) KSM later gave a second, uncoerced statement to the FBI after he was transferred to Guantánamo Bay, but this “clean” confession has never been made public.

“That’s basically been the subject of the last two years of litigation,” McDermott said. “Whether that confession would ever be introduced into evidence at an actual trial.”

In his view — and that of most others inside and outside the government who have been involved in the Guantánamo trials — a plea agreement along the lines of the one accepted and retracted last week is the only logical way to bring the proceedings to an end. The structure of the military tribunal’s proceeding was still being hashed out when Austin called a halt, but it was reportedly to take the form of a “mini-trial,” which would have been held next year. The fact-finding process might not deliver justice but might have offered some answers to lingering questions. McDermott and I discussed a few areas where KSM might be able to fill in the blanks.

Recruitment: How did Atta and the other members of the “Hamburg cell,” as it was later called, end up enlisting in Al Qaeda? No one knows for sure whether they traveled to Afghanistan with prior knowledge of the plot or the intent to become martyrs, although McDermott has a strong theory. “I spent at least a year and a half trying to figure out how they were recruited and came to the conclusion that they weren’t,” he says. “They just showed up, and they happened to show up, in one of the great coincidences of world history, just as KSM had gotten approval for the plot from Osama bin Laden, and they were looking for people to execute it. They wanted people who were sufficiently technical, who could learn to fly airplanes, and they wanted people who were familiar with the West, who preferably spoke English. And these dickheads from Hamburg walk in.” But even if it all was just happenstance, KSM could explain how these four outsiders ended up meeting bin Laden and taking control of the most ambitious terrorist attack in history.

Planning and implementation: Although bin Laden inspired the plot and took credit for its destructive success, he was apparently not deeply involved in the planning. “Command and control — I don’t think there was a lot,” McDermott said. Bin Laden delegated the planning to KSM, who delegated implementation to Atta. Even so, KSM might be able to provide answers to some mysteries. “There are some oddities,” McDermott says. For instance, he asks, why did Atta drive to Portland, Maine, the night before the attack and board a connecting flight from there to Boston, where he joined the rest of his hijacking team? “It’s just stupid. It doubled the risk of the exposure.” It has long been speculated that Atta might have needed to meet someone there.

Similarly, no one knows why members of the hijacking plot took separate flights on various occasions to Las Vegas. Investigators on the staff of the 9/11 commission visited Las Vegas to try to figure out the city’s significance. “I think bin al-Shibh would know that,” McDermott says, and he would have reported back to KSM. “Vegas is a great place to go because there’s a constant flux of people. You don’t stand out. But I don’t know, maybe they wanted to get laid.”

Co-conspirators: For decades, some families of 9/11 victims have been fighting the U.S. government for information about connections between a pair of 9/11 hijackers who spent time in California and a mysterious man named Omar al-Bayoumi, who had links to Saudi intelligence. If it had happened, presumably some of the questions at KSM’s hearing would have concerned the possibility of Saudi support, but McDermott thinks this line of inquiry is unlikely to lead anywhere. “Skeptical doesn’t begin to describe it,” he says of his opinion about the speculative Saudi connection. “It’s us being unable to accept that this bunch of yokels did this. What would the Saudis have done? The whole thing cost maybe a quarter-million dollars, and most of that was for hotels and apartments. That’s not a lot of money. You don’t need a state actor.”

KSM definitely knows something, though, about the role of Pakistan, which gave support to jihadist groups through the ISI, its intelligence service. “One thing I would like to know,” McDermott says, “is how KSM managed to just live in public in Pakistan for two years after 9/11, conducting business as if nothing had happened.” And, of course, bin Laden also ended up living quietly in the garrison town of Abbottabad. “If I were looking at anybody, it’d be at the ISI.”

As for local support, Atta and the other key members of the plot spent well over a year in America, taking flight classes, shopping at Walmart, and doing nothing to draw the attention of law enforcement. That is a long time to operate undercover. But despite throwing all its resources into the investigation, the FBI never managed to find any evidence of an Al Qaeda network in the U.S. One intriguing connection the hijackers made was with the American-born imam Anwar al-Awlaki. When he was questioned after 9/11, some investigators suspected he knew more than he was letting on, and he later became an extremist and was assassinated by a U.S. drone strike in Yemen. But it remains unclear whether Awlaki was an Al Qaeda sympathizer at the time, or radicalized afterward, by the War on Terror and his own experience of being ensnared in the 9/11 investigation.

Motive: Atta never wrote a manifesto describing what he hoped to accomplish by flying a passenger airliner into the World Trade Center. “Atta was such a tortured individual,” McDermott says. “I don’t think Atta is much different than the guy who tried to shoot Trump. He’s just a warped person in some regard. But he was making his mark on history.” Although the attack is always portrayed as an act of religious extremism, there is evidence to suggest Atta and the members of his Hamburg cell were also steeped in radical politics. When a German newspaper went through a library of materials Atta left behind at a study group he led in Hamburg, it found a library of tracts about globalist conspiracy theories. Ziad Jarrah, the group member who took the controls of United 93, made a martyrdom video that was recovered by U.S. intelligence and introduced at the military trial of an Al Qaeda propagandist, in which he delivered a speech about the “New World Order” and striking “the head of the Jewish and crusader snake.” It may be that they had more in common with American extremists than is generally appreciated.

In 2007, in his only extensive statement before the military tribunal, KSM described himself as an anti-imperialist soldier, saying “the language of war is victims.” He said he was “responsible for the 9/11 Operation, from A to Z,” and also claimed he had planned to destroy other landmarks, including the Sears Tower and Big Ben, to blow up nuclear plants, and to assassinate Presidents Clinton and Carter, as well as the pope. But as McDermott points out, KSM has never fully explained what incited his hatred of the United States, where he lived as a university student. Prior to 9/11, KSM operated semi-independently of Al Qaeda, and the fragmentary evidence suggests he saw bin Laden as something of a religious flake.

“My main interests are motivation,” McDermott said. “I would like to know, beyond the usual cant, how KSM came to be what he became. He is one of the greatest mass murderers in history, and we really don’t know why he did it.” History will have to wait for the answer.