This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On the morning of October 8, I looked up bleary-eyed from the computer on which I’d been scrolling nonstop for hours and said a version of what I have since heard so many Israelis say: “They hate us. They all want us dead. There’s no peace to be made with animals like that.” My husband stared at me in horror. He placed his hand on my shoulder, shaking me, and said, “How can you be saying this! You’re the one who taught me how to feel about Palestine!”

I remember in his eyes an expression not merely of dismay but of betrayal. Who was this unrecognizable person with a snarl on her face and revenge in her heart? My urge was to shout at him that he didn’t understand, he couldn’t understand, but I managed to choke down my fury. It’s not that he shook me out of my incoherent, visceral rage. But he reminded me of who I’d been and, more important, who I wanted to be. Pretend, I said to myself. Pretend you are who you once were, until you are able to find yourself again.

Though this spinning of my moral compass was dramatic and shattering, it was not an unfamiliar feeling when it comes to Israel. I grew up in a devout family, but our religion was Labor Zionism and our god was Israel, the dream of a homeland for the Jews built on principles of secular socialism. Our place of worship was the kibbutz, our origin myth my father’s immigration to Israel from Canada in 1948 and his founding of Kibbutz Kissufim in the Negev Desert, one of the kibbutzim that was invaded by Hamas militants on October 7.

I was born in Jerusalem, though by the time I was a toddler we were back in Montreal and eventually moved to the United States. Where once my parents had made aliyah — literally “gone up” to Israel — now we were yordim, those who had “gone down,” a pejorative appellation that carried with it the shame of having betrayed our deepest values.

My father spent his career making up for this breach of faith. He was an exquisitely talented fundraiser for various Israeli causes, regaling busloads of wealthy Jews with tales of his early years as a chalutz, a pioneer. In 1975, the San Francisco novelist Herbert Gold went on one of the “missions” my father led to Israel. In a column about the trip, he writes that Leonard Waldman “tracked me to my bed. He had no mercy,” adding, “That’s why we are here: to see where the money is needed, to see where it goes, to have our arms twisted.” My father said to him, “Money helps to make us righteous. Why else should we live, if not to be righteous?” Gold wrote, “His eyes are glowing. He looks happy. He looks like a man in that state of exaltation.” My father continued, “It’s good to have a Jewish heart. It’s good to have a Jewish soul. It’s good to be a Jew.”

Like all observant parents, mine raised me in the tradition of their beliefs. I went to Zionist summer camps, visited Israel, lived for a year in high school on Kibbutz Kfar Blum in the Galilee, and did my junior year abroad at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Afterward, I decided to make my life in Israel on Kibbutz Hazorea, not far from Haifa, where my eldest brother, Yosi, lived. I was fulfilling my father’s Zionist dream.

As a citizen of Israel, I was obliged to serve in the military, a duty I welcomed. My father had served in the Palmach, an elite Jewish fighting force that merged with the Haganah, the Zionist paramilitary organization that eventually became the Israeli army. Yosi had been a highly decorated officer in the paratroopers, while another brother had also served. I fully intended to follow in their footsteps, but when budget cuts caused the IDF for a short period to offer draft exemptions to girls, I jumped at the opportunity. Without really understanding or interrogating why, within two months I had packed my bags and left the country. I was 22 years old.

Over the next years and decades I disengaged from Zionism, eventually becoming an advocate for Palestinian rights and sovereignty. Along with my husband, I edited a volume of essays called Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation. I gave lectures about the injustices of the Nakba and of occupation, I wrote op-eds and made television appearances defending the necessity of Palestinian self-determination, I received awards as a “Defender of Palestine.”

This advocacy gave me purpose, but in the nine months since the Hamas attack and the Israeli invasion, I have grown increasingly hopeless, buffeted by feelings of despair, shame, anger, and disgust both with myself and the country of my birth. I felt powerless in the face of the catastrophic horror Israel is raining down on the people of Gaza.

That was how I found myself accepting an invitation from a group of American rabbis to participate in an antiwar demonstration at a border crossing between Gaza and Israel. This would be my teshuvah, my repentance, for my violent yearning for vengeance as well as an affirmation of the fundamental values I had in those moments betrayed. What I didn’t realize then was that this trip would take me back in time to dig deeper into the inherent contradiction and willful blindness of the “liberal” form of Zionism that motivated my father when he first came to, in his own words, “colonize” Palestine for the Jews in 1948 — an ideology that lost much of its political influence long ago and was, for me, shattered by October 7 and the consequent invasion of Gaza.

On October 7, Kibbutz Kissufim, about a mile from the Gaza border, was the site of a long and intense attack in which 14 residents were killed and one, 86-year-old Shlomo Mansour, was taken hostage, the oldest of those still held in Gaza. It is also where the likely last victim of the Hamas attack, Reuven Heinik, the manager of the dairy farm, was shot by a militant when he returned to the kibbutz on October 9 to care for the cattle.

Though I had never before visited, Kibbutz Kissufim has played a starring role in the narrative of my father and my family for as long as I can remember. In June 1948, when he was 23 years old, my father, a socialist and Zionist, left Montreal and made his way to Palestine to be part of the forming of a Jewish state and to join the Jewish military forces in their battle against the Arab armies. As he was an aspiring journalist, his letters home, which my siblings and I came across only after his death in 2021, are long and filled with ideological musings and elaborate descriptions.

In the first letter, upon reaching Palestine via Marseilles, he writes that the Jews are “all slightly slap-happy at the thought of having their own country.” It is, he writes, “the freest country in the world,” adding that “the country is now Eretz Israel and that’s the way it stays.” Throughout that summer, he writes with increasing exhilaration about the settlements and farms cropping up over areas conquered by Jewish forces. He writes that the Jews are “making the country look like a garden where it once looked like a desert,” repeating the phrase used by many Jews who arrived in Palestine in the 1940s, and one I myself learned in Hebrew school 35 years later.

Within days, he joined the Palmach and was immediately promoted to the role of “instructor.” The Palmach had no officers, he said, just instructors and comrades, so this 23-year-old, whose military experience had until then consisted of a short stint in the Canadian ski patrol, was now effectively an infantry officer responsible for training and leading other young volunteers. In a letter home, he reassures his family, “This business of being an instructor now means that I will probably never get close to an Arab … I am not running up and down the front line trenches with a pistol strapped to each hip and a tommy gun in my hands.” He adds, “With the Arabs a weapon doesn’t have to be lethal to frighten them. If it makes a big boom and throws up a flash of light and lot of smoke they almost die of fear.”

Adventure and euphoria burst from these letters: “I never stop being impressed with the miracle of a nation being born. At the moment mother and child both seem to be doing well. The infant is squalling lustily and the cry is heard around the world. The world may not like the cry but it can’t help hearing it, and it can’t deny that the country is now alive.”

My father wrote these letters less than three years after World War II, when the extent of the genocide of the Jews of Europe and the grotesqueries of the death camps were still becoming clear. He wanted desperately to be a part of the creation of a new kind of Jew, one who would not — as the narrative went — be so easily and efficiently slaughtered.

There is a gap in the letters in my possession until August of the following year, after the Jews won the war and the State of Israel was formed. The letters of 1949 are replete with idealistic passages about the satisfactions of communal living, the fulfillment of the Zionist dream, and the pride my father took in his role in a blossoming socialist utopia. He had by this point joined with another group of young people — a garin, or seed — to found their own kibbutz. He is a leader of the garin, he writes, the man responsible for managing efforts to get a loan and buy a plot of land on which to settle.

During this period, the garin lived in a series of established kibbutzim, learning the skills that would be necessary when they founded their own. Some of the young pioneers, he writes, are working at “a rocky spot south of Haifa.”

By October, my father was desperate to set out for the Negev Desert. “I will go out and break my back to develop the Negev because it is a task that I think satisfies my self interest and the interests of the commune (which to me are the same thing),” he writes. His life became clear to him: “My own future I see no place else but on a kibbutz.” He goes into great detail about his efforts to purchase the tractors, trucks, and fishing equipment the fledgling kibbutz members need to establish their commune, known by now as Kibbutz Kissufim.

My father mentions in the last letter I have that he has married a girl he met two months before because she is as committed to their enterprise as he is and because she, like him, is a leader of the group. “We are both ‘machers’ in the garin,” he writes with obvious satisfaction. They lead a number of committees, and it is in their tent that people gather. Only late in the letter does he seem to realize what has been left unsaid: “And, of course, we fell in love with each other.”

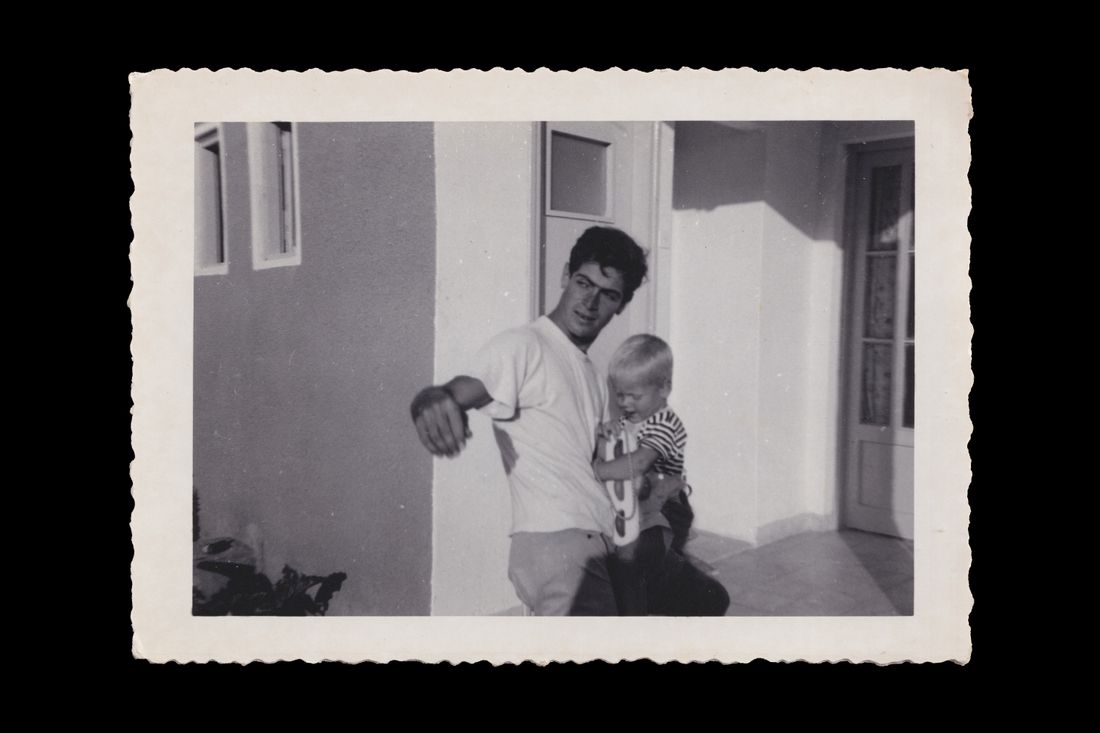

The young man of these letters is someone I recognize. From the time I was a child, the only way I connected with my father, a man who maintained a strict emotional distance from his family, was through tales of these early days on the kibbutz. About this, the normally reticent man would talk, sometimes for hours. These were the years, he told me, when he felt most himself, when he was doing what he was meant to do, living the reality of his ideology as a Zionist and a socialist. From the moment he left the kibbutz and Israel, he wanted only to return, and had it not been for my mother, whom he married after his divorce from the socialist pioneer and with whom he moved back to Canada after a failed attempt to make a life in Jerusalem, he would live there still. I would have — should have — grown up on the kibbutz, a child of the socialist and Zionist dream.

In none of our conversations about the early years did my father talk about his service in the Palmach or about the war. The reason became clear to me on the first day of my trip to Israel this past March, when I asked Yosi, the eldest of the four children of my father’s first marriage, to drive south with me so I could visit Kissufim for the first time.

It was also then that I had my first inkling of the chasm between my perception of the war in Gaza and that of many of my family members and friends. When we planned our trip, Yosi mentioned he had been taking food to the border. My planned demonstration with the rabbis would involve attempting to take food into Gaza through the Erez Crossing, also known as the Beit Hanoun Crossing. I assumed this was the border Yosi meant. But within moments, it became clear that the border he had been driving to was in the north, and the people to whom he brought snacks and meals were the IDF soldiers stationed there.

On our drive south to Kissufim, Yosi announced firmly that he was neither a subject of nor a partner in my investigations. “I’m just the driver,” he said. And for the next two hours, he talked without pause. When our father told his parents that he would avoid combat in 1948, it was either a wish or a lie, Yosi told me. In fact, he was a machine gunner who would have fought in intense battles in which those Arabs he claimed ran at the sound of a loud noise tore his unit to shreds, likely killing many of the young people he had recruited and trained. “It’s about six months that there is continuous fighting and they continuously lose people,” Yosi said. “You go out at night and you don’t know if you’ll come back in the morning.” For some, those battles continued after the war, into the early 1950s. “They did crazy things. All kinds of stupid raids.” Raids on whom, I asked. “Gaza,” Yosi said.

I sat stunned. Raiding Arab villages long after the end of the war was not part of the picture of Zionist idealism my father had painted for me. During raids, Yosi said, young kibbutzniks would steal donkeys or other things in retaliation for similar thefts by the Arab villagers across the border in Gaza. These incursions and counter-incursions were not limited to thefts. There are stories of killings on both sides.

As a result of his experiences during the war, Yosi said, our father suffered for his entire life from untreated PTSD.

PTSD. It lands with a thud, at once shocking and so very obvious. My father’s silences, punctuated by bouts of rage. The jobs he lost, one after another, despite his magnetism and competence. The furious battles with my mother, which I had always blamed on her temper, her lack of control. I knew he had bipolar disorder, but I had not for a moment considered it was complicated by trauma. “It’s a very personal thing, being post-traumatic,” Yosi said. “Establishing a relationship that has emotions in it is very, very difficult. One of the most difficult things for post-traumatic syndrome people is to express their emotions. They close up, and they shut up.”

It was at least in part a result of this trauma, my brother believes, that my father and his then-wife left Kissufim. How long did the family live there before they moved away, I asked. “A year,” Yosi said.

A year? Years of preparation, of scrounging for loans, trucks, and supplies; of recruiting people to join with them; of being a leader, a macher; of traveling abroad to recruit more members — and they left after a single year?

Yosi remembers his mother arranging for a truck, loading it up, and heading north to Kibbutz Kabri in the western Galilee, one of the kibbutzim on which the garin had trained in previous years. They left, he said, because his mother fought with everyone; she was a troublemaker. And because she and my father fought with each other, I assume. My parents’ shouts shook the walls of our house. I can only imagine what effect they would have had on a tight-knit, thin-walled kibbutz community.

In 1962, by then with four children, they were expelled from Kabri, apparently because their presence was intolerable and destructive to the group. My father took the children to Canada as kibbutz emissaries, where he attempted to found “Camp Kissufim,” a short-lived summer camp for North American kids. The place he had planned to spend his life was so close to his heart and imagination that he named his summer camp after it.

As my brother and I wandered the pathways of Kissufim, I tried to assimilate this information. The place is empty now, the surviving members evacuated to a hotel by the Dead Sea, only a few coming back during the day to work on repairing the damage of the Hamas attack. The buildings are burned and shot up; the gardens have returned to desert. The brightly painted cartoon murals on the bomb shelters are riddled with bullet holes. In the dining hall, we found a row of photographs from the first days of the kibbutz: groups of young people gathered together, working, laughing. My father is in none of these pictures.

I was reminded of how when I called the kibbutz historian after my father’s death and asked about burying his ashes in the cemetery, the man told me he had not heard of my father and could find no record of him. That my father was there at the founding of the kibbutz I have no doubt — I have a letter from September 15, 1949, written on official letterhead that reads in Hebrew and English, “Kissufim, Canadian Group,” with a return address of a post-office box in Rehovot — but what am I to make of the profound difference in magnitude between the role Kissufim played in his life, the role it played in the narrative of my family history, and the fact that he made so little an impression upon the place, his presence, which he described as critical to its formation, forgotten?

My father elided from his stories that the family was unable to stay in Kissufim and was then pushed out of Kabri. When he and his new wife, my mother, returned to Israel, they moved to Jerusalem not because she refused to live on a kibbutz, as he told me, but because he was not allowed back. He never admitted to me and perhaps even to himself that he had failed at the communal life for which he believed he was so suited. I am certain that even he didn’t know that this failure, according to my brother, was in part a result of the trauma of the war about which he never spoke.

Over the years, and especially after 1967 when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza, my father was forced to reckon with the “conflict,” the word he, like most Israelis, used to refer to the oppression of the Palestinian people. He supported “peace” and an end to occupation as part of the ethos of socialism and liberalism. My parents despised the Likud Party. They were members of Peace Now, an organization that works in opposition to the settlements and advocates for a two-state solution, and they donated to the New Israel Fund, a U.S.-based NGO that supports social justice and equality in Israel. In an interview on CBS Reports, my father denounced the military intertwinement of the U.S. and Israel and called for negotiation and peace. He celebrated the Oslo Accords and the efforts of Yitzhak Rabin toward a version, albeit a hollow one, of an independent Palestinian state, and he grieved when Rabin was murdered by a Jewish terrorist.

But this dream of a leftist version of Zionism, the dream my father nurtured for his entire life, cannot exist without denial of the crimes and atrocities committed both during the founding of the state and after. My father’s fantasy of his war years and of the years on kibbutz is one all but devoid of Arabs. In his letters, he writes little of the Palestinians who were displaced, and only then with a casual racism that jars me, referring to them derisively as “Abdullah.” He does not acknowledge that the “rocky spot south of Haifa” where he and the members of his garin learned how to farm was Kabara, once a Palestinian village of over 117 homes. He makes no mention of the village of Al-Zraiye, 2.2 kilometers from Kissufim: 4,790 people driven from their homes in 1948.

I don’t mean to single out my father in this. Israeli society as a whole has conspired to eradicate the memory of the more than 500 Palestinian villages depopulated and destroyed in 1948, the three-quarters of a million people expelled, despite attempts by some Jewish Israeli historians starting in the late 1980s to more accurately rewrite the narrative of the Nakba. This denial continues to this day.

A decade ago, I went to Hebron with a group that included Israeli journalists to see Al-Shuhada Street, a once-bustling Palestinian market on which only Jews and foreigners are now allowed to tread, the Palestinian residents having been either evicted or forced to enter their homes through rear doors and windows. Al-Shuhada Street had been “sterilized” of Palestinians more than a decade previous, but an Israeli journalist who joined this group kept murmuring in wonder, “It’s not to be believed.” This grotesque violation of human and civil rights was going on an hour and 15 minutes from her home in Tel Aviv, but she, a journalist and self-described leftist, had managed to keep from knowing anything about it.

The Jewish left in Israel has been in a downward spiral for decades. The social-democratic Labor Party dominated Israeli politics until 1977 and alternated power with Likud until the early aughts. According to Dahlia Scheindlin, an Israeli public-opinion researcher writing in Haaretz, “During the early 2000s, the portion of Jews who defined themselves as left wing dropped by half, from roughly 30 percent to about 15 percent,” and “by 2019, the left was drifting to the range of 11 to 14.” In the first few months after October 7, that number dropped to the single digits, though it has since crept back up to 12 percent.

The reasons for the left’s withering are numerous and well documented: They include the increase in the number of “revisionist Zionists” who assert Jewish dominion from the river to the sea and the political enfranchisement of Mizrahi Jews, whose families came primarily from the Middle East and North Africa. Israelis of Mizrahi ancestry are the country’s largest ethnic bloc and vote overwhelmingly for Likud and other parties further to the right. But a hardening against the Palestinians has spread throughout Israeli society, including on the left, a hardening that is reminiscent of the callous disregard with which my father and his fellow socialist Zionists held the people whose lands they appropriated. There is a phrase that Jewish Israelis who consider themselves left or centrist have taken to using since October 7: Hitpakachti. It means “I have sobered up,” from believing that peace is possible, from believing they can live alongside Palestinians.

Every Saturday night in Tel Aviv, thousands gather to protest against Netanyahu, a regular feature of many people’s weeks. “Let’s meet for dinner and a protest,” a friend said to me. There are a number of protests going on at the same time, each in its own designated area. In the center is the largest group, the Kaplanists (named for the square where they gather), organized around deposing Netanyahu and returning the hostages. The families of the hostages have their own areas. One group of families refrains from criticizing Netanyahu for fear of alienating him; the other is adamant that Netanyahu himself is what stands in the way of the hostages’ return. When I attended, I heard heartbreaking speeches from these family members, a mother berating Netanyahu for caring more about his political skin than her son’s life, a wife longing for her husband. People throughout the crowd held signs illustrated with the hostages’ faces. Yet in all those speeches, not once did I hear from the stage a denunciation of the war or any mention of the suffering of Palestinians in Gaza.

I have heard myriad stories from friends about this shift on the part of people who once considered themselves progressives. One recounted a conversation with someone very close to him, “an amazingly sweet, sweet guy who has always voted left of center, one of the last in Jerusalem fighting for liberal values,” who stated unequivocally that the Israeli government should allow no food aid into Gaza. “I know what a kind, loving, intelligent, smart person he is,” my friend said, but he was legitimizing starvation as a tactic to be used against civilians to pressure Hamas. In January, Yigal Mosko, a journalist who has written extensively about military and settler abuses in the West Bank, posted a tweet justifying the destruction of Gaza framed as a letter to the people.

Hello Gazans. You will soon return to your homes and find that they have been completely destroyed. You will clap your hands in despair and cry bitterly, “Why?” … Because of Kafir and Ariel and Shiri Bibas, because of the twin babies Guy and Roy Berdichevsky whose parents were murdered … When your heroic sons finished raping and murdering and entered Gaza with the abductees, you went out into the streets to cheer … You will now return to the same streets and will not recognize them. The buildings collapsed, the infrastructure was demolished, the roads were plowed with the tank chains. Yes, many thousands of you were also killed. What did you think would happen? … You don’t have a roof over your head to mourn them? Maybe dig a new hole, you’re good at that. You burned hundreds of millions on your terror tunnels instead of investing in a better future for your children.

Tomer Persico, a Jewish Israeli philosopher with a long career of advocating for freedom of religion in Israel, posted a tweet, since deleted, with images of Gazans taking advantage of a rare respite in the bombing to cool off in the ocean, implying that this moment gave the lie to claims of genocide.

Roni Aboulafia, a filmmaker and peace activist who believes a negotiated two-state solution is the only way forward, has a compassionate explanation for why even liberals and those who consider themselves humanists in Israel are not focused on the suffering of the people of Gaza. “We are all living through trauma,” she said. “Every day brings new stories of the horrors that survivors went through and are still going through. The hostage situation is a very, very painful open wound.” She added, “We are in a collective state of processing that limits our capacity to absorb Gazan pain and accept our accountability for it.”

Very few Israeli Jews even talk about what is happening in Gaza. When I asked why, I was told again and again that the Israeli media do not cover events on the ground. The public does not see images or hear stories of dead Palestinian children or devastated communities. Al Jazeera, the only network to reliably report on the horrors ongoing in Gaza, was recently banned in Israel. Yet we live in an interconnected world; we live online. Though it’s true that our social-media and news silos can isolate us from the views and opinions of others, it is hard to imagine that anything but a concerted effort could keep a person from knowing the toll the war has taken on Palestinian civilians.

This carefully nurtured ignorance reminds me of my father and his stories about kibbutz life in the 1940s, which never included raids across the border into Gaza, the driving out of villages full of people, the murder of civilians. It reminds me of another saying we learned in Hebrew school: “A land without a people for a people without a land.”

This denial is not ubiquitous, however. As I wandered through the crowds at the Saturday protests, I encountered a smaller group, many of them clad in the purple of Standing Together, a Jewish and Palestinian organization that supports coexistence. I found the Gush Neged haKibush, the Anti-Occupation Bloc, banging drums and demanding peace and an end to the war. You can wander among these various groups as in a shopping-mall food court. Buy a T-shirt here, take a poster of a hostage there. Shout an anti-Netanyahu slogan here, bang a drum against the occupation there.

We Jews are gifted in the art of memorialization, and you can watch the narrative of October 7 and its aftermath being created in real time. From the moment you step off the plane in Ben Gurion Airport, you see posters of the hostages. The images are everywhere in the country, in train stations, on billboards, and at “Hostages Square,” a rallying space that has grown up in a plaza in front of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. There are tents for each community attacked, a merch table where you can purchase memorabilia like a “Bring Them Home” dog-tag necklace. There are art installations, including a long dining table set with empty seats, one for each hostage.

Close to Kissufim, at the sight of the Nova Music Festival, another memorial has sprung up, photographs of the dead nailed onto small posts, each growing from a nest of red ceramic flowers. There are tour buses in the parking lot, and the Hasidim have set up a Mitzvah Mobile like the ones you find on New York street corners with Orthodox men in sidelocks inviting Jews to light Shabbas candles. Ultrareligious families wander through the memorial looking at the photographs of young women they would have cursed had they seen them walking so scantily clad through their neighborhoods. I couldn’t bear to walk through what seemed to me a ghoulish tourist attraction exploiting these young victims.

The most troubling of these memorials is a mock Hamas tunnel made of concrete in Hostages Square. I feel almost ashamed of criticizing this installation, erected as it was by grieving and desperate families, but when I walked through the narrow, dim space, the walls decorated with posters of the hostages, messages to them scribbled in colorful marker, I felt bleak, not because it made me realize the hostages’ plight, trapped in the tunnels of Gaza. I ache for these people and for their agonized families, and I am enraged that the government has refused to prioritize a negotiation for their return. But to me, this tunnel felt, even more than the Nova memorial, like a grotesque theme park. For the majority of Jewish Israelis, the only grief they can feel is their own, the only dead worth mourning are their own.

Here is another family story, this time of my brother. Yosi was a proud officer in the IDF who fought bravely against Egyptian forces during the Yom Kippur War in the Battle of the Chinese Farm in the Sinai, saving the lives of many. He is the recipient of a medal of honor, a highly decorated hero of the land of Israel. But what he remembers most about the war is the mettle of his opponents, which came as a shock to him. He and his men had been indoctrinated with a narrative of supremacy in which victory was inevitable. “We were the super-people, and they were monkeys on the trees,” he said. Of a battalion of 350, 50 were killed, including most of the officers. Half of their soldiers were wounded. “They mopped the floor with us,” Yosi said. “They fought well.”

Yosi was seriously wounded, and immediately upon reaching the hospital, he could feel the trauma creeping up on him. He felt like a profound failure, an officer who had not protected his men. He had no one to talk to about this aside from other wounded soldiers. He told me he would wheel himself in his wheelchair from bed to bed, telling his story and listening to theirs. This is what he’s proud of, not his actions in the war. To this day, people reach out to him and tell him that by letting them talk, he helped them. When I asked Yosi if at that time or afterward he was able to talk to our father about their shared trauma, he looked at me as though I were crazy.

As he spoke about the supposed inferiority of Israel’s enemies, I couldn’t help but recall that line from one of my father’s letters about the Arabs being frightened by a “big boom.” The story of the Arabs’ cowardice was as much a fiction in 1973 as it was in 1948 — and as it was before October 7. “It was an enormous fuckup,” Yosi said of Netanyahu’s attempts to prop up Hamas, believing the group had lost the will to fight and could be isolated from the broader Palestinian cause. “We were completely betrayed.”

Only a country in deep denial could believe the Palestinians in Gaza would live in perpetually abject but passive misery. It is a denial so ingrained that Jewish Israelis extend it even to Palestinians who live outside the occupation in Israel proper. Yara Shahine Gharablé, a history graduate student and activist, encountered a Palestinian flag in Jerusalem during a school trip in eighth grade and only then realized that she herself was Palestinian. “I went to the internet and started reading, and at the end of the day I started crying,” she said. “I asked my mother about the Nakba; she’s like, ‘I do not want to talk about this. You’re making me nervous.’” Palestinians like herself, Shahine Gharablé says, feel that since October 7 there has been only one story they are expected and allowed to tell. Jewish friends asked why they had not heard her publicly condemn the Hamas invasion. “And I was like, and I haven’t been hearing from you since, I don’t know, 76 years,” she said. Since October 7, the divide has only grown between her and her Jewish classmates, including those she once considered allies and friends. “One community is going this way and the other is going this way, and it’s only getting escalated in a sharp way,” she said.

Inas Osrof AbuSeif, a Palestinian artist and photographer, lives in the same orchard her mother’s family has farmed for generations, the last Palestinian-owned orchard in the city of Jaffa. When Inas was growing up, there was no easily accessible Arab school, so she went to Jewish schools where she learned Hebrew instead of Arabic, the history of Israel, and even the Hebrew Bible, a required subject in the Israeli curriculum. “Every single thing in my identity is taken away from me,” she told me. “I taught myself how to read Arabic alone. I don’t know how to write.” She fell silent. “Even my thoughts,” she added sadly. “It’s all in Hebrew. I don’t think in Arabic.”

At home, she was instructed not even to utter the word Palestine for fear of being blacklisted or attacked. A year ago, she decided to embrace the word, to speak it aloud. But then Hamas attacked. “On the first day, the police came to our neighbor who posted something on social media, and it was like watching a horror movie. They came with 30, 40 police officers, and they were masked.” When I asked Osrof AbuSaif about the phrase Hitpakachti, she again fell quiet. After a moment, she said, “I don’t want to be in partnership. I don’t want to be in a place where I always have to convince the other side that I’m human and my kids are worth living.” Maybe, she said, she has also sobered up.

Her use of that phrase, of course, is spiked with an irony entirely missing when it is spoken by left and center-left Jewish Israelis for whom to sober up means to reject the possibility of coexistence, to embrace the canard that Israel has no “partner for peace” among a Palestinian community of more than 3 million people. By the upside-down, looking-glass logic of modern liberal Zionism, a person of conscience and principle becomes “sober” by embracing a willed oblivion, remembering only incidents of Palestinian terrorism and forgetting the generations of Palestinians who have sought redress through myriad legal and nonviolent ways. This “sobering up” is to focus on incidents of antisemitism on American college campuses, which are analyzed in excruciating detail in the Israeli and U.S. media. It is to embrace the balm of victimhood, to wrap ourselves in the mantle of an age-old hatred that led to the murder of 6 million — victimhood that has now been transferred to October 7, which is referred to again and again, including by Netanyahu and President Biden, as the worst tragedy the Jews have experienced since the Holocaust, in order to expiate the shame of the war in Gaza.

To “sober up” is to forget the 750,000 Palestinians expelled and the 500 villages destroyed in 1948 and the massacres and abuses since. It is to mourn the 1,139 murdered in the horrific massacre by Hamas on October 7, the 240 taken hostage, 70 of whom are believed to still be alive, while ignoring the tens of thousands killed in Gaza, among them aid workers and physicians, the elderly and women, and children dismembered and burned alive.

Erez Crossing was formerly the sole pedestrian entry point between the northern Gaza Strip and Israel. It was through Erez that the few Gazans with jobs in Israel would travel when such travel was permitted. It was there that leftist residents, many of them elderly, from the kibbutzim in what’s known as the Gaza Envelope, the area of Israeli territory that wraps Gaza from the north and east, would wait for the patients needing medical treatment and drive them to appointments at Israeli hospitals. And it was the Erez Crossing that the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades took control of in the attack they called Operation Al-Aqsa Flood, which the Israelis know by its date in the same shorthand of catastrophe as 9/11.

I was there on the dusty road at the invitation of Rabbi Alissa Wise, founder of Rabbis for Ceasefire. It’s Passover, she said, and the Haggadah’s instructions are clear. Ha Lachma Anya: “Let all who are hungry come and eat.” The irony of reciting these words at a Seder while famine in Gaza is imminent, with fully half of the population experiencing catastrophic food insecurity, was more than these religious leaders could bear. As Rabbi Brant Rosen, of Congregation Tzedek Chicago, told me, “The only way I could honestly say those words this year was while I was literally carrying food provisions toward the Gaza border.”

The plan was simple. The group would fill a pickup truck with basic foodstuffs — half a ton of flour and rice — and drive as close as possible to the Erez Crossing. When we were stopped, as was inevitable, we would take what we could in our arms and push forward. Few actually expected the small convoy to make it all the way to the border. The Israeli military controls the area. That the action was symbolic, however, did not defeat its purpose. What, after all, is religion if not a conglomeration of symbols? Matzo, which many of the rabbis carried, symbolizes the bread of the poor, the bread of liberation. The tallits they wore symbolize the word of God. There’s nary a word spoken or an action taken in any religion that is not primarily symbolic.

When we arrived, we were greeted by police officers clad in black body armor, standard-issue machine guns slung over their backs. Reinforcements in the form of a tank eventually arrived. We began walking alongside the pickup full of food. Somehow, without noticing it, perhaps because I was buoyed by adrenaline, I ended up ahead of the group, a bag of rice on my shoulder, a white flag in my hand. My path was blocked by a police officer. I shuffled right, he shuffled with me. I moved left, he did too. We engaged in this synchronized waltz for a few moments until the others caught up.

At this point, a few of the rabbis stepped forward to speak, including Avi Dabush, the director of Rabbis for Human Rights. Dabush is a resident of Kibbutz Nirim and a survivor of the October 7 attacks. He, his wife, and her children spent eight hours in their shelter listening as Hamas militants swarmed the kibbutz. On Nirim, five people were murdered and five others taken hostage. Dabush told the assembled group that the only hope for his children, his kibbutz, and all “from the river to the sea, Palestinians and Israelis” is to have peace. “This is the meaning of Pesach, the liberation of all people. If you have power, don’t use it against the other.”

When the police began pushing us to the side of the road, we sat down. Rabbi Alana Alpert of Congregation T’chiyah in Detroit led us in songs I remembered from Zionist summer camp. We raised our arms to show we were not a threat, and the police began picking us off one by one. I was arrested soon after Rabbi Wise. Some of the officers were more hostile than others, one or two grabbed me harder than might have been necessary to haul off a 59-year-old, five-foot-tall woman recently diagnosed with osteoporosis, but I was neither bruised nor hurt. I spent nine and a half hours in the Ashkelon police department in relative comfort, in an office rather than a cell, before being interrogated and then released.

As I sat for those long hours in the police station, I tried to make sense of this experience in the context of both my family history and the history of the Israeli peace movement. While the dwindling of the Israeli left is a tragedy, the reality is that in some way there never was an Israeli left to begin with. People like my father defined themselves as socialists devoted to the eradication of class distinction; democratic control over political, economic, and industrial institutions; and, as he wrote, “the interests of the commune” over their own self-interest. But their commune, their classless society, was composed exclusively of Jews. It was as if it had never occurred to him or them that the Palestinians who lived on the land they viewed as the Jewish homeland were also people who had a fundamental right to be part of it.

But even if liberal Zionism is rotten to its core, there are still millions of Palestinians and Jews between the river and the sea, and none of them are going anywhere. And so the remnant of the Israeli left protests. They give testimonies to Breaking the Silence, they get arrested while demonstrating, they act as a buffer between the trucks carrying food to Gaza and the violent religious Jewish extremists trying to destroy that food. Jews and Palestinians create common cause in organizations like Standing Together and A Land for All. And I carry a bag of rice to a checkpoint a mile from the Gaza border knowing full well it will never reach its destination.