No Democratic presidential nominee has ever assembled a more progressive campaign website than Joe Biden. Blue America’s presumptive standard-bearer has endorsed an expansion of collective-bargaining rights that drastically increases labor’s leverage over capital. He’s called for waging war on exclusionary zoning, and making Section 8 housing assistance an entitlement program that would be available to all Americans whose material circumstances qualify them for aid — policies that meaningfully reduce housing segregation and slash child poverty by more than a third. Biden has proposed making public college free for most Americans, tripling federal funding for low-income school districts, raising the federal minimum wage, and making Washington, D.C., a state.

But a campaign website promise is worth about as much as a verbal IOU from a miserly amnesiac. America’s veto-point laden legislative system, polarized politics, and right-leaning Senate map all make passing laws exceptionally difficult. Even when a single political party manages to secure control of the presidency and both houses of Congress, it typically struggles to pass more than one piece of big-ticket legislation. Biden can tell the AFL-CIO that he wants to legalize secondary boycotts or put workers on corporate boards or devolve all political power to workers’ councils — once in power, all he needs to do to renege on such promises is point to Joe Manchin and throw up his hands. Which is to say, expressing support for a policy means little, absent a commitment to prioritize its passage once in office.

For this reason, the most encouraging aspect of Biden’s new climate plan is that it is also his plan for economic recovery.

During the 2020 primary, Biden called for spending $1.7 trillion on renewables, energy-efficient infrastructure, and research and development on a wide range of “moon shot” green technologies, among other projects. His plan also aimed to achieve net-zero greenhouse emissions by 2050 through the establishment of an “enforcement mechanism” (ostensibly, some kind of carbon tax) that would ratchet up until CO2 emissions fell to a level consistent with that goal. This was an order of magnitude more ambitious than any policy Democrats had entertained four years earlier, but still exponentially less ambitious than a rational and humane response to the climate crisis would require.

But that was the primary. Now that Biden’s secured the nomination, he’s walking back that proposal — and pivoting to the left.

On Tuesday, the presumptive Democratic nominee unveiled a new climate policy, informed by the work of the Biden-Sanders unity task force. Now, instead of investing $1.7 trillion over ten years, Biden calls for getting $2 trillion out the door in just four. As for zero-emissions targets, 2050 is so January 2020; today, Biden wants America to run on 100 percent clean electricity by 2035.

The new policy would spread $2 trillion across a wide range of initiatives, including revamping the nation’s infrastructure, upgrading and weatherizing millions of buildings, providing every major U.S. city with “high-quality, zero-emissions” public transit, constructing 1.5 million ecofriendly affordable-housing units, subsidizing the growth of America’s electric-car industry, and creating a climate conservation corps to clean up abandoned gas wells and other ecological blights. This is not the Green New Deal (GND) as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez conceived it; her version included Medicare for All and a federal jobs guarantee. But it is remarkably close to the narrower version of the GND outlined by the progressive think tank Data for Progress in September 2018.

All this would mean little in the absence of indications that Biden views his climate policy as a governing priority, rather than a mere campaign ploy. But there are two reasons to believe that he sees it as the former. First, there is the policy’s timing. We aren’t in the heat of a primary in which Biden is jockeying for the support of progressive interest groups. We’re in the general election. And, as recent polling from the New York Times demonstrates, from a purely political perspective, Biden has no real need to shore up his left flank. Former supporters of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are nearly unanimous in their backing of the Democratic nominee over Trump. Meanwhile, due to the president’s bungling of the pandemic, Biden has opened up a nearly double-digit lead in national polls. To the extent that Biden regards this lead as insufficient, he has about as much incentive to water down his policy program in the hopes of flipping disaffected Republicans as he does in shrinking the distance between his platform and Bernie Sanders’s. It is true that many aspects of Biden’s new policy enjoy broad popularity. But the number of U.S. voters who pay close enough attention to climate policy to discern the distinctions between Biden’s new plan and his old one — and who were unwilling to support a Democratic nominee with a $1.7 trillion climate plan, but will support one with a $2 trillion plan — is almost certainly miniscule. There just isn’t much reason for Biden to adopt this policy if he doesn’t genuinely wish to enact it.

Secondly, and more important, Biden’s vow to spend $2 trillion in four years doesn’t just represent a more substantively ambitious response to the climate crisis — it also establishes massive green investment as the cornerstone of his vision for economic recovery. The aim of rapidly dispensing these funds is as much Kenyesian as ecological: The point is to replace depressed private-sector demand for capital and labor with public investment in a sustainable future.

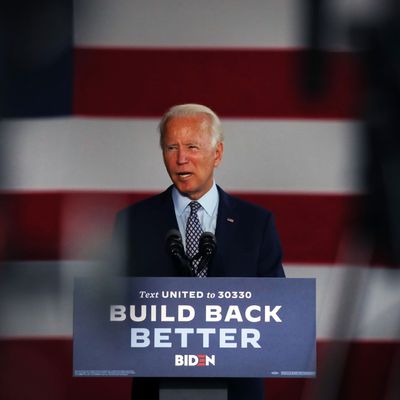

This fact is explicit in Biden’s rhetoric, which frames the climate agenda as integral to his “Build Back Better” vision for post-COVID America. But the aim is also embedded in the policy’s details. Most of the items on Biden’s green itinerary include an estimate of the number of jobs they will create. In fact, the policy prioritizes the creation of high-quality jobs over maximizing carbon reduction per dollar, by mandating high wages and collective-bargaining rights for the workers it enlists.

All of this makes climate more than just one more issue on a campaign website chock-full of them. America’s unemployment rate is likely to remain near Great Recession highs in January 2021. Mass business failures are displacing millions of workers. If Democrats secure full control of the federal government next year, economic recovery legislation is likely to be at the top of the congressional agenda. Biden’s plan means that, in such a scenario, climate change will share top billing.

In ordinary economic times, mobilizing congressional support for massive federal intervention in the economy can be difficult, even if such intervention is ecologically necessary. The silver lining of the present calamity is that it has rendered private investors incapable of achieving a socially acceptable level of unemployment, and has thus broadened support for Uncle Sam stepping in to pick up the slack. And when the federal government is supplying the capital, it can allocate labor and real resources on the basis of social utility rather than market profitability. Biden’s new plan indicates that he recognizes this opportunity, and intends to capitalize on it.

To be sure, the obstacles to enacting a plan as ambitious as Biden’s present one remain myriad. Even with Biden’s lead over Trump near all-time highs, Senate control remains a toss-up. If Chuck Schumer secures a tiny majority, centrist Democrats from states dominated by fossil-fuel interests will have significant leverage over all legislation. And although Biden is signaling comfort with abolishing the filibuster if Republicans obstruct his agenda, not every Senate Democrat is onboard.

Nevertheless, the odds that the Democratic Party will secure the power to govern in 2021 — and will use that power to substantially mitigate our ever-deepening ecological catastrophe — are higher now than they’ve ever been.