Nobody said ‘Thank you,’” the bishop complains. “I didn’t get one thank-you.” He goes on: “You want to know why? Because I was portrayed as a villain. I was portrayed as a failure.” He’s repeating himself now as though he’s in the throes of a sermon, working over a phrase he plucked from Scripture. “Nobody said ‘Thank you.’ Not even the mayor. He said, ‘You did good,’ or whatever. Nobody said ‘Thank you.’”

Bishop Lamor Miller-Whitehead and I are in the first-floor home office of his six-bed, seven-bath, 9,000-square-foot Paramus, New Jersey, home. He’s at the desk where he now preaches to his online flock, seated before a computer, some bottles of Issey Miyake and Acqua di Parma cologne, and a worn, heavily Post-it-noted red Bible. The 44-year-old bishop, whose loud and patterned wardrobe suggests an haute couture Riddler, is dressed down today in a charcoal Calvin Klein suit and a solid brown tie.

We’ve been discussing his first star turn of the year: the Tuesday in late May when he attempted to personally deliver to the authorities the alleged Q-train shooter Andrew Abdullah, who was wanted for the murder of a Goldman Sachs employee named Daniel Enriquez. Miller-Whitehead had said the suspect’s aunt, one of his parishioners, had called seeking his help, leading him to try and broker an exchange with the NYPD and Mayor Adams, a mentor. Abdullah and his family eventually showed up at Legal Aid instead. Amid the frenzy, the bishop’s arrival at Manhattan’s Fifth Precinct — empty-handed but wearing a Fendi suit jacket and driving a Rolls-Royce SUV — fueled suspicions of clout-chasing. “I know he pulled up in front of all the cameras in his big truck,” says one police lieutenant when I ask what role the bishop played in apprehending the suspect.

“This thing really started the fire,” Miller-Whitehead says. “‘The bling-bling bishop’ — this, that, and a third.” Because the bishop’s real run of tabloid infamy, and his grievance with his portrayal in the media, was just beginning. In late July, while delivering a livestreamed sermon before a few rows of worshippers at his small nondenominational ministry in Canarsie, Miller-Whitehead, along with his wife, Asia DosReis-Whitehead, the First Lady of the church and a bishop herself, were robbed at gunpoint by three assailants. The thieves made off with a reputed $1 million worth of jewelry, including a $390,000 Cuban link chain and a $75,000 Rolex.

Zapruder-style scrutiny of the video footage followed. Online, rival pastors mocked the church, which is located in a rented space above a Haitian restaurant, and questioned Miller-Whitehead’s devoutness. The local papers were happy to print the very many details of his criminal history, from a 2008 identity-theft conviction — for which he served five years in Sing Sing — to a 2021 lawsuit alleging he siphoned $90,000 from a woman he promised to help buy a house. (“I don’t owe it to her, and I’m not going into that,” the bishop tells me.)

The public’s harsh conclusion about the robbery was that any man of the cloth so well appointed, with that checkered a legal past, preaching in such an incongruously shoeboxlike venue, must have staged the whole thing in an insurance-fraud scheme. Here was the bishop as Monty Python’s “Bishop,” a swagged-out vigilante cleric who appeared at crime scenes too late and didn’t seem all that religious. Shortly after the robbery, the rapper Fat Joe, a friend, interviewed the bishop live on Instagram. “I asked a couple of cops, and they were like, ‘Yo, that shit was a setup,’” he told the bishop, who stared back at him helplessly, wearing a pink sweater and pink glasses. “I asked some gang dudes on the street, and they were like, ‘Nobody violates the church.’” Sympathetically, Fat Joe broke down the bishop’s dilemma. “It’s kinda messed up that you got robbed, but people don’t believe you got robbed.”

Complicating the matter of his integrity was the Fat Joe–ness of it all: the bishop’s bewildering, Waldo-like tendency to show up where you least expected him, flanked by legitimate VIPs. To spend time with Miller-Whitehead is to hear a litany of charmingly questionable boasts and name-drops. While attending Sheepshead Bay High School in the 1990s, he says, he was one of FUBU’s “first models” and walked the runway for Tommy Hilfiger in its Aaliyah-era heyday.

At the very least, the connections he claims to the hip-hop community, forged before he went to prison, do check out. Foxy Brown is his cousin. 50 Cent once spoke at a church event he organized. The rapper 6ix9ine, incredibly, got a sentence reduced partly on a promise to do community service with him. Fivio Foreign stumped with him last year during the bishop’s quixotic run to replace Eric Adams as Brooklyn Borough president. (He finished last in the Democratic primary with about 4,000 votes. “The result was crazy,” says the bishop. “It didn’t add up.”)

In any event, the tabloids and the online detractors weren’t so quick to note that, just a couple months after the robbery, two men were arrested and charged in federal court, with the NYPD and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives claiming the score. “Armed robbery is an intolerable crime, but to commit such an act during a religious service is incomprehensible,” said the ATF in a statement.

At his house, the bishop pulls up surveillance video of the robbery that hadn’t been seen publicly. In it, frightened churchgoers can be seen hitting the deck; jewelry is brusquely yanked from his neck. Just 3 of his 15 stolen pieces were insured, he says, and none of them were recovered. “Where is everybody at right now?” he asks. “It’s not that I’m not the hot story no more,” he clarifies, answering himself. “No. It’s, ‘You guys got egg in your face.’ Y’all thought I set it up for an insurance scam, all to be in the face of the media. That’s why you’re not talking about it.” Perhaps a wide conspiracy is yet to be revealed. A simpler explanation seems likelier: That a famously opulent pastor may have been targeted for a robbery because he livestreams sermons while decked in gems and precious metals.

Defiant, the bishop has gone on the reputation-management warpath. In September, he filed $20 million defamation suits against his two chief internet foes, commentator De’Mario Q. Jives and Christian media personality Larry Reid, who have dined out on bishop content. Miller-Whitehead sued Reid for saying he was a scammer and would be headed back to prison; he sued Jives for alleging he was a drug dealer and a gang member and that he was wearing the same jewelry before and after the robbery. “I call these guys the Wendy Williams of gospel,” the bishop tells me, which they might take as a compliment. Jives, when I call him, clarifies what he meant: “I said, ‘Dude, where are you getting all this money from? Are you part of a gang or something?’ It was a question.” In November, the bishop filed another defamation suit, this one for $50 million, against a radio DJ called Miss Jones. “I’m handing out lawsuits for Christmas,” he posted on his Instagram page.

He also recently stopped preaching in person. “People laugh that a gun was put in my 8-month-old baby’s face, and people laugh that my church was robbed,” he says. “I’ve lost so many members and had members crying to me for weeks. I had to pay for therapy for my members.” He put the Paramus house up for sale for $2,999,999 (he bought it for $1.6 million in 2019). “People don’t know that after YouTubers put my address and my home up, there was an attempted home invasion,” he says. (He later took it off the market.)

In the bishop’s telling, he tried to bring a suspected criminal to justice, then was robbed mid-sermon at gunpoint — and he’s the bad guy? “If this would have happened to a Caucasian pastor, if this would have happened to a Joel Osteen or one of them, it never would have been like this,” he says. Investors in various business ventures, he claims, have bailed on him thanks to the renewed scrutiny of his criminal record.

“Millions of dollars I’ve lost because of people like these YouTubers,” the bishop says. “They turned me from a victim to a villain.”

In June 1978, when Lamor was 6 weeks old, his father, Arthur Miller, a Crown Heights businessman and community leader, was choked to death by police officers, sparking sustained protests throughout the summer. No cops were indicted. Lamor was raised by his mother, who worked for what was then called the Board of Education. “I remember my mother couldn’t afford Nikes. I had to wear Olympians,” says the bishop, explaining his eventual taste for luxury.

He went to three colleges (there was a basketball scholarship, he says), dabbled in modeling and acting, and cut a few hip-hop tracks before becoming a mortgage broker. He rented an office on the 57th floor of the Empire State Building — his “friends from FUBU” were on the 66th floor — and says he employed a team of 12. But in 2006, he was charged with trying to buy Land Rovers and opening lines of credit using the names of customers from the Long Island car dealership where his then-girlfriend worked and landed in Sing Sing two years later.

Upon his release in 2013, he founded Leaders of Tomorrow International Ministries and got himself consecrated as “a bishop in the Lord’s Church” three years later at a Baptist parish in Brooklyn. But this was not a prison-conversion story, he insists. He was first ordained as a minister before he went upstate, and anyway, he maintains he was “illegally convicted.” Given his penchant for designer threads, the bishop has been described as a “prosperity gospel” preacher, though he doesn’t like the suggestion that he’s promising wealth to his parishioners: “I tell you how to get in alignment with the word of God, so therefore you can be in the position of the blessing.” Otherwise, his religious principles can run, let’s say, traditional. “It’s not that I’m homophobic or whatever,” he tells me, “but if my church has a question — ‘Bishop, what does the Bible say about homosexuality?’ — I preach on what the Bible says.”

Miller-Whitehead began mingling with the Central Brooklyn power elite, hosting holiday turkey giveaways and an annual “Church Honors Hip-Hop” service. In 2016, he met Asia, who now has her own online ministry, plus a mentorship program and retail concern called the UaReACHAMPION Empowerment Network.

The bishop also became close with then–Borough President Eric Adams, who bonded with him over his father’s killing. “Everybody looks at the man as a mayor — I look at Eric different. I look at him as a person who helped save my manhood,” he says. “When you don’t know your father, you don’t even know what that side of your DNA is, why you act the way you do.” After the bishop tried unsuccessfully to organize a gospel concert at the Barclays Center, he says, Adams sat him down and counseled him to learn from his failures. “It was something that my dad would have said to me during that time, I would think,” he says. The relationship went both ways: In 2014, Miller-Whitehead wrote a letter of support on behalf of Adams’s friend Robert Petrosyants, a restaurateur being sentenced on federal money-laundering charges, telling a judge they had partnered to teach children about healthy eating.

It was 2016 when the bishop earned his first brush with tabloid infamy, after the New York Post reported that he’d been touting nonexistent initiatives with the Brooklyn DA’s office, the NYPD, and the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce. Adams had his back: “I was arrested at 15 years old,” he said at the time. “And because people embraced me when I was arrested, I embrace Lamor Whitehead.” While the bishop says their relationship has grown distant since Adams became mayor, the two appeared together in the summer of 2020, shortly after the killing of George Floyd, at an event commemorating the death of Miller-Whitehead’s father. “Mr. Miller was the first ‘I can’t breathe’ in modern times,” Adams said. “A young child left without a father because the institution supposed to help and protect decided to hurt and murder.”

All that was before he was front-page famous. Now, Miller-Whitehead is caught between justifying his extravagance and disavowing his public image. He seems wary of being stereotyped by the white media as a figure akin to Reginald Bacon, the self-aggrandizing reverend from The Bonfire of the Vanities who was almost certainly modeled on a young Al Sharpton. On the matter of the clothes, his take is that nobody criticizes the pope. He clicks around on his computer and pulls up an article from 1908 in which Pope Pius X’s vestments were estimated to cost $50,000 a year. “And that’s just his garments,” Miller-Whitehead says. “The Bible says a blessed man is a man that takes care of his children’s children.” (True. Proverbs 13:22.) “David was a king, royalty. Solomon was the wealthiest and the wisest king to ever live. This is Scripture! The apostle Paul had money. Peter. All of them. How do you think they was getting around?”

At the same time, he’s aware that his own vestments aren’t necessarily helping his case. “If it was not me, I would have believed it,” he concedes about the inside-job gossip. “‘Look at the suits that he wears. He must have been robbing the church.’” Eager to burnish his reputation, Miller-Whitehead spends the first 40 minutes of our interview riffling through court documents related to his identity-theft conviction, claiming he was railroaded in complicated procedural ways. He also alleges that his first attorney was in cahoots with the Suffolk County DA who prosecuted him. This isn’t a totally outlandish suggestion, given that the DA, Thomas Spota, who was later disbarred and sent to prison, supported a judge in vacating a cocaine-possession sentence for the lawyer. (Miller-Whitehead tends to avoid addressing the substance of the case.)

His fixation on refuting detractors can have the effect of making him look worse. Over the summer, Miller-Whitehead posted a Google Voice transcription of a voice-mail that an FBI agent purportedly left with one of his parishioners seeking to chase down a rumor that he had bilked someone of $150,000. The man who planted the rumor, the bishop said, was his nemesis, the pastor-influencer Larry Reid. When I called Reid, he told me the FBI had been calling him since late July seeking dirt on the bishop. (Obviously, the FBI did not confirm or deny this.) When I ask the bishop if he knows of an FBI investigation into him, he says, “It’s a bunch of garbage, man.” In the meantime, the two of them have been going back and forth about whether Reid inspired Miller-Whitehead to buy his model of Rolls-Royce.

As for his income streams, the bishop speaks vaguely of real estate, singling out an apartment complex he owns in Hartford, Connecticut. The Post reported that he’s been trying to jack the rent and evict tenants, who in turn claim they’re protesting crummy living conditions. Otherwise, he says, “I buy properties, I flip properties — you know, I get into deals.” Making those deals, he argues, requires a certain flair. “If I pull up in a Honda or I pull up in a Rolls-Royce to close a deal: In this society, who will close the deal faster?” he asks.

Assuming you have those kinds of wheels. In 2020, a judge entered a default judgment against him for failing to make payments on a Mercedes-Benz and a Range Rover. A pattern seemed to form. In 2021, a judge levied a $335,000 judgment against him for failing to pay back a lender on the Paramus house. In September 2022, a lender sued alleging he had defaulted on a loan used to pay for renovations to the Hartford complex. “When you’re in real estate, people are going to sue you,” he says, declining to address specific charges. “It’s frivolous.”

Most Sundays, his two-hour sermons hew to a handful of Bible verses, though lately the parables have been coming from his own life. A few hours after we finished talking at his house, he delivers an emergency sermon in response to the murder of the rapper Takeoff to an audience of about 225 on Instagram Live. “As soon as somebody dies, we say RIP for a week and then it’s gone, it’s on to the next,” he says. But by minute six of his sermon, he’s stewing about his failed borough-president run, and by minute nine, he’s on to the accusations he faked his own robbery. Both topics strike him as variations on the day’s theme: “I was getting bombarded by my own race, and everybody was ridiculing me.” In real time, commenters begin critiquing him for self-centeredness. “If you don’t like it, get off my page,” he tells them. “Or I’m gonna block you.”

What’s wrong, he asks me, with being “godly and glamorous”? He returns to the dashed attempt to apprehend the subway shooter. “My whole day, my whole life is now out there because I tried to broker something so this kid wouldn’t die and so we can catch an alleged criminal,” he says, explaining he didn’t want the cops to shoot the alleged gunman before he could be properly arraigned. The bishop was simply performing professional services. “It’s not about loving the camera,” he insists. “Okay, if a firefighter saw a fire but he didn’t have his uniform, right, is he not supposed to save people with his skills? If a police officer didn’t have his uniform on and sees a robbery, is he not still a police officer? Just because I’m dressed for the day and have a Fendi coat on, I’m not supposed to be a pastor?”

What does he want? Perhaps some acknowledgment of his tribulations: “I represent that, with Jesus, you can go through the storm.” And maybe some earthly reward. “I think I should get the front page,” he says. “You don’t think I should get it? I think I was the face of the year.”

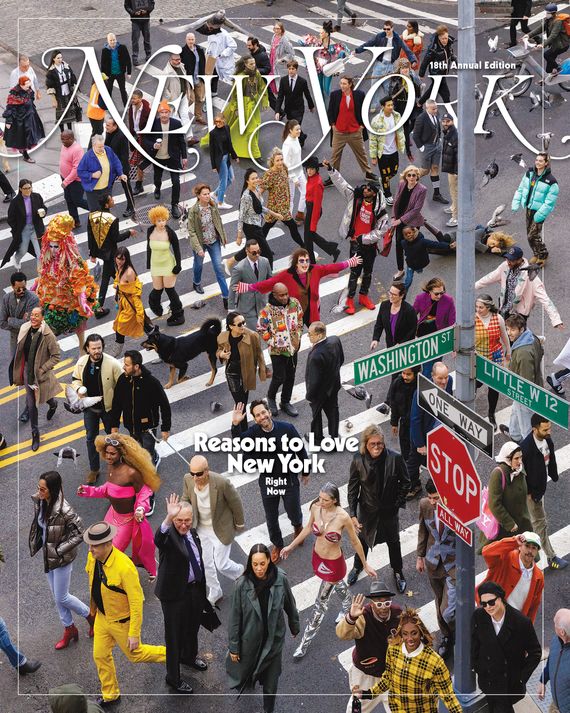

More reasons to love new york

- 39 Reasons to Love New York Right Now

- A $45 Million Effort to Make Pregnancy Less Deadly in Brooklyn