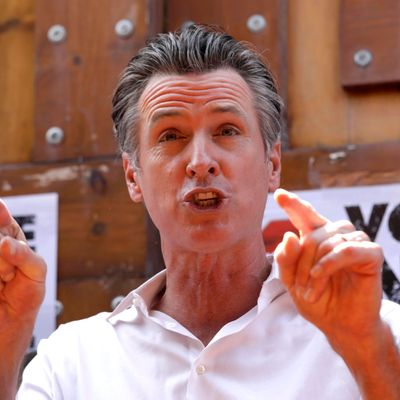

Earlier this month, California sent out gubernatorial recall mail ballots to all 22 million registered voters with a deadline of September 14 for completed ballots to be postmarked (or dropped off at in-person voting centers). Its target is Governor Gavin Newsom, who was elected in 2018 by a 62-38 margin. Although California is a profoundly Democratic state these days (the Donkey Party enjoys supermajorities in both state legislative chambers and nearly a two-to-one voter registration advantage), Newsom is in some real peril of being recalled. If he loses the vote, he will be immediately removed from office and replaced – quite possibly by a Republican.

How could this possibly happen? It’s complicated. Here’s a guide to Newsom’s predicament.

Newsom has been hit with a perfect storm of bad timing

At any given moment, there are always recall petitions circulating against every California governor. But they generally fail to obtain the number needed to secure a ballot line (12 percent of the votes most recently cast for the relevant office, in this case, 1,495,709 verified petitions) in the limited time made available (160 days). The Republicans who began a recall drive against Newsom because of his generally progressive views got very lucky in two respects. First, a state judge gave them a four-month extension of the qualification deadline (until March 17, 2021) because of the difficulties in signature collection created by the COVID-19 pandemic, which was a bit ironic since Newsom’s support for COVID-19 prevention policies soon became central to the recall campaign.

But what really sent the campaign into overdrive was a gaffe committed by the governor on November 6, 2020, when he violated his own policies restricting indoor gatherings by attending a (maskless) birthday party for a wealthy lobbyist friend at one of the state’s (and the country’s) most exclusive restaurants, the French Laundry, in the Napa wine region. Aside from Republicans, small-business owners and public-school parents who were already chafing at Newsom’s stay-at-home orders and restrictions on in-person instruction exploded in anger at his apparent hypocrisy, and the petition campaign reached its goals with relative ease.

Arguably, a third incident of bad timing occurred on July 1, when Lieutenant Governor Eleni Kounalakis, a Newsom ally, used her discretion to set the date of the recall election for September 14, hoping that an economic recovery driven by receding COVID-19 cases and rising vaccinations, and booming state revenues, would dispel the recall threat. The Delta variant, of course, almost immediately brought back the pandemic crisis in California as elsewhere, and while Newsom has tried hard to defer to local governments in setting prevention policies, the Hot Vaxx Summer era of good feelings evaporated.

Republicans are psyched about the chance to purge Newsom and win a statewide election

What has made the recall viable is that California’s Republican minority looks likely to punch well above its weight. For one thing, Newsom is almost a parody of everything Trump-era Republicans hate. He’s a wealthy cultural progressive from San Francisco (that despised Sodom-by-the-Bay in the imaginations of cultural conservatives everywhere) with close ties to Silicon Valley (another object of conservative fury lately) whose self-confidence oozes arrogance to his detractors and who always looks like he’s just stepped out of a fashion shoot. For another, Golden State Republicans know they are outgunned: They haven’t won a statewide race since 2006. And their last big breakthrough was another recall election back in 2003, when they succeeded in dumping Gray Davis in favor of their own Arnold Schwarzenegger. Could history repeat itself? Perhaps, if every Republican turned out. At the time, it was seen as the best, and perhaps the only, opportunity the GOP might ever have to choose the governor of California.

The sense that it might happen was enhanced by the decision of Team Newsom to discourage Democratic politicians from joining the vast field of candidates running to replace the governor if he is indeed recalled. The way California’s much-criticized system works, the recall election includes just two ballot lines: one asking if voters want to recall (i.e., remove) the incumbent and a second selecting (by a simple plurality) a replacement if a majority votes “yes” on the first question. So a small minority of voters could select a Newsom successor if things break right — something of an irony for a state that now requires majorities of the vote for victory in regular general elections under a top-two primary system (all candidates from all parties compete in a “jungle primary” with the top two finishers proceeding to a general election).

Democrats are not psyched about the need to save Newsom

All along, the big fear in Newsom’s camp has been that the state’s large Democratic majority won’t bother to vote in a recall contest thanks to a combination of complacency and confusion. And polls that distinguish between registered and likely voters have been showing a big gap between Republican and Democratic interest in the elections.

You obviously won’t hear this from Newsom-backing activists, but another problem is the governor’s lack of the kind of intense support that drives people to the polls in relatively low-turnout special elections like this one. Even Californians who approve of his job performance (steady if not large pluralities) don’t seem to like him a lot.

This has led recall opponents to increasingly strident negative attacks on the Republican sponsors of the effort. Newsom’s lavish ad budget has featured a series of messages (some offered by national Democratic figures like Senator Elizabeth Warren) labeling the recall as a continuation of the Trump reelection campaign and even of the January 6 insurrection. The assumption is that Democrats who won’t go out of their way to save their governor might be aroused by the chance to displease the hated 45th president and his MAGA bravos.

Newsom is embracing a risky message, telling voters to ignore the replacement race

Without question, the 2003 recall election haunts today’s recall opponents. There is a strong belief (perhaps better described as a mythology) that Davis lost because his lieutenant governor, Cruz Bustamante, jumped into the replacement race and drew voters into supporting the recall without mustering enough support to beat Schwarzenegger. So, Team Newsom not only kept credible Democrats from running to replace him; they’ve also tried to discourage Democratic voters from answering the second question on the ballot about their preference among replacement candidates. As Politico noted recently, this “one-and-done” messaging may be confusing or even angering the very voters Newsom needs:

“It’s kind of counterintuitive to forgo your right to vote,” said Barbara O’Connor, director emeritus of the Institute for the Study of Politics and the Media at Sacramento State. “Everyone is in a conundrum about what they should do.”

What makes the pay-no-attention-to-the-replacement-candidate-behind-the-curtain instruction to Democrats especially confusing is a new round of anti-recall ads attacking replacement front-runner Larry Elder (a veteran libertarian-leaning conservative talk-show host with a rich history of provocative on-air comments and some personal baggage) as “to the right of Trump.” If Elder is so evil, shouldn’t Democrats vote for someone else in the field of 45 other candidates, some of whom identify as Democrats? It’s unclear.

The mail ballot factor is a wild card

Early on, California election authorities decided to proactively send mail ballots to all registered voters, just as they did in the pandemic general election of 2020. They can be returned via enclosed postage paid envelopes (if they are postmarked by September 14 and received by September 21, they will count) or dropped off at voting centers (and in some counties, a drop box) on September 14. So, if California Democrats do become motivated to vote, it won’t be hard for them to do so. And you do have to wonder if Donald Trump’s demonization of mail ballots during and after the 2020 presidential election might still inhibit Republicans from voting that way, even if there remains an option for turning in ballots in person.

There’s even more drama on the horizon

Sparse polling of the recall election (and polling of special elections is always difficult) has shown a tightening contest on whether or not to remove Newsom. Elder also has a growing lead in the replacement race, though at least one poll has YouTube financial advisor and self-identified Democrat Kevin Paffrath actually topping the field. Team Newsom probably has mixed feelings about future polling, fearing both confirmation of the trend favoring Newsom’s removal and less alarming numbers that might let Democrats relax back into complacency and indifference.

The anti-recall effort has the resources to dominate paid advertising down the stretch (along with personal campaigning by Vice-President Kamala Harris and later, perhaps, President Joe Biden), but it will need to settle on a consistent message and combat the growing word of mouth among Republicans that this is the moment they’ve all been waiting for. Another variable involves the internal dynamics of the replacement race. With no general election on tap (again, if Newsom is recalled, the replacement winner instantly becomes governor), Elder’s Republican rivals have no reason to hold back from savagely attacking him from one angle as Democrats attack him from the other. If late polls show a rival (most likely former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer or 2018 candidate John Cox) catching up with the talk-show host, it could have a hard-to-predict effect on turnout or might even vault Paffrath into the governorship should Newsom fall.

In the event a Republican does become governor of the largest state in the country — a state that contributed 5 million votes to Joe Biden’s 7 million vote national plurality last year — lusty cries of triumph will erupt throughout MAGA-land, and “Democrats-in-disarray” narratives will exceed even their current level in media circles, conflating a Newsom disaster with the Cuomo disaster and the Kabul disaster. Had Gavin Newsom given the French Laundry a wide berth last November, the risk of such a catastrophe for his governorship and his party might have been avoided altogether.