This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One evening last July, a convoy of SWAT vehicles and police vans pulled to a stop in front of a single-story tan stucco home in the Las Vegas suburb of Henderson, Nevada. To the area’s residents it was an undoubtedly curious scene; Henderson is considered one of the safest communities in America. At the target house, an officer pulled out a bullhorn and began shouting to the people inside. “This is the Las Vegas Metro police department. We have a search warrant for the residence. Come out with your hands up.”

Eventually, the garage door rose, revealing Duane “Keefe D” Davis, a 60-year-old Black man with a bald head and a graying beard. Davis was instructed to put his hands over his head and walk backwards down the driveway, where he was detained while officers searched the house. According to court records, the police confiscated everything from 11 .40-caliber cartridges to a Pokémon-themed flash drive. Not long after, Davis was arrested and charged with one of the 20th century’s most infamous unsolved crimes: the 1996 murder of rapper Tupac Shakur.

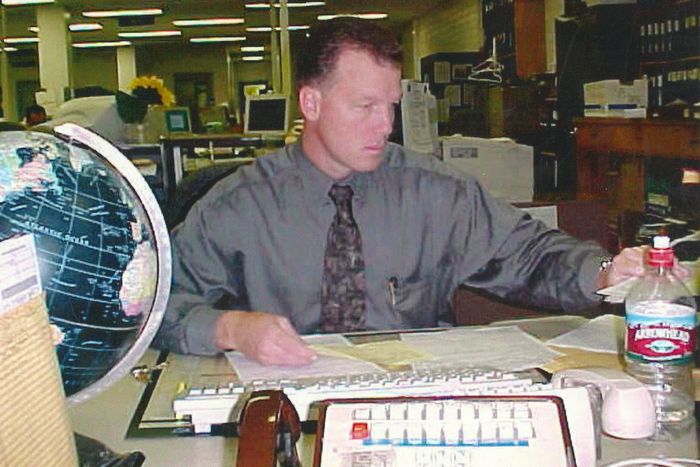

Even for those closest to the case, the news came as a shock. Twenty-five hundred miles away, a former LAPD detective named Greg Kading was in a hotel room in Boca Raton, Florida, when his phone chimed with an incoming text. Keefe’s been arrested, it said. Kading, like Keefe, was 60, and his age had started to show. His brushed-back hair was thinning, his goatee had gone gray, and gravity pulled at the sides of his eyes, softening the hardest features of his face. Until his retirement in 2010, Kading had been a hotshot cop working some of the LAPD’s most complicated cases: racketeering, extortion, murder. He earned a Medal of Valor from the Department of Justice, and reached the LAPD’s highest ranking as an investigator. And yet, for all his experience, he had never expected a text like this to come.

Fifteen years earlier, Kading had secured a secret confession from Davis in Tupac’s killing. But at the time, a legal arrangement had barred prosecutors from using the confession in court. Davis had walked free. For years, Kading had lost hope. “I had publicly said, ‘I don’t think that there will ever be an arrest in this,’” he recalled. Now, it appeared that something had changed. “I feel that it’s part of divine intervention,” he told me recently. “Most other people would call it karmic justice.” Alone in his hotel room, Kading pumped his fist into the air, overcome by a heady combination of excitement and relief.

The private moment didn’t last long. Within minutes, his phone started ringing and didn’t stop for the rest of the day. National news and niche podcasts alike wanted his expert opinion. Ever since retiring, Kading had spun his experience on the case into a profitable second act that included self-publishing a book, producing a documentary and TV series, and dozens, perhaps hundreds, of podcast and YouTube-channel appearances. His claims to have solved the murders of both Tupac and rival Christopher Wallace, a.k.a. Biggie Smalls, or the Notorious B.I.G., had made him something of a celebrity in the niche world of hip-hop-related true crime. But with celebrity had also come controversy. As Kading’s profile grew, so did the criticisms from former colleagues who described his police work as sloppy at best and dangerously reckless at worst.

Until recently, those squabbles had largely remained the fodder of podcast fanatics and Biggie-Tupac truthers. But Davis’s arrest has changed all that. Kading’s LAPD history is facing renewed scrutiny and legal questions surrounding how the confession he secured from Davis could potentially upend the prosecution’s case. Which presents the question: Could the cop who cracked one of the most notorious cold cases in history also have a hand in its undoing?

In December, I visited Kading at his home in Rancho Cucamonga, California, where he had agreed to walk me through his role in the tangled investigation that led to Davis’s arrest. In interviews, Kading can come off as combative; he has a habit of calling his critics “fucking stupid.” But in person, I found him breezily self-possessed. He greeted me warmly in a Hawaiian shirt and set us up to talk around a large felt poker table in a room he’s been converting into a podcast studio. When I asked what he did with his free time, his answer was immediate: golf.

It was a far cry from what Kading described as his “wayward youth.” Born in Reno, Nevada, to a pair of casino workers, he was arrested as a teenager for brandishing nunchucks and claims to have taken his first hit of acid at the age of 10. A possible career in law enforcement didn’t emerge until his early 20s after his best friend suffered a spinal-cord injury and Kading returned home to care for him. The friend’s father, a lieutenant with the local sheriff’s department, offered to help Kading get hired as a deputy. “It was never a lifelong dream,” he told me. “It was just a good job.” In 1988, after a ride-along with some cops in Los Angeles, however, he saw the light. “God, this city’s badass,” he remembers thinking. “There’s so much action.” He applied to join the LAPD soon after.

It was the height of the city’s gang era. “Today’s victim is tomorrow’s suspect,” was how one L.A. County sheriff’s deputy described his tenure during those years. “It was all hell breaking loose.” At the time, L.A. was averaging a thousand or so homicides a year. Kading thrived in the high-adrenaline world of foot chases and drug busts. “I wanted to be tough or at least feel tough,” he said. Before long, he was recruited into the LAPD’s controversial CRASH anti-gang unit, where he admitted to “manhandling” gang members in a similar manner as the officers who beat Rodney King into submission in 1991. “I loved being a good guy,” he would later write in his memoir, Murder Rap. “And I loved it when the good guys won.”

In 1996, when Tupac Shakur was killed after leaving a casino in Las Vegas, Kading barely noticed. He had by then been promoted to the federal task forces investigating L.A.’s biggest and most complicated cases: organized gang activity and drug trafficking, among them. Similarly, the killing of Biggie Smalls in a drive-by shooting outside L.A.’s Petersen Automotive Museum six months later, also failed to register. “It was just like, whatever,” Kading told me. “Some celebrity rapper got killed in L.A.”

It wasn’t until nine years later that Kading finally got involved. By then, the Tupac and Biggie murders were already among the most controversial cold cases in American history. The inability of police to crack either case had transformed the pair into symbols of the kinds of institutional failures that could allow two of the world’s most famous Black artists to be struck down in their primes, with no one to answer for it. Las Vegas police would later say that they had a bead on Tupac’s killer within days of the shooting, but that their efforts were stymied by a code of silence among the gang members involved. What they are less likely to admit is that the lead investigators showed up in Compton in clunky cowboy boots and were all but laughed out of the interrogation room by the hardened gangsters they had arrived to question. “They didn’t have a clue,” said Bob Ladd, a former Compton police officer who aided in the Shakur investigation.

The investigation into Biggie’s killing was equally inept. Infighting, egos, and conspiracy theories derailed it from almost the beginning, resulting in Voletta Wallace, Biggie’s mother, filing a $400 million wrongful death lawsuit against the LAPD in 2002. She had been inspired by an article in Rolling Stone featuring Russell Poole, one of the lead detectives on the case, who came to believe that rogue cops were responsible for her son’s murder. The lawsuit threatened to bankrupt the police department. “It has nothing to do with dollars and cents,” Wallace said at the time. It had to do with “honesty, integrity, and coverup.” (Wallace declined to speak for this story.) After four years of courtroom battles with Wallace’s attorneys, the LAPD’s top brass eventually concluded that the best way to prove the police hadn’t killed Biggie was to figure out who did.

In the spring of 2006, Kading got a call from an LAPD detective named Brian Tyndall asking him to join a resurrected investigation into the superstar’s death. “There’s this big lawsuit going on,” he remembers being told. “We want some outsiders looking at this.” Kading recommended partnering with the feds. Not only could the FBI bring experience and funding, there were also the optics to consider. If the task force found that LAPD officers were not involved, it would undercut Wallace’s case — and with the feds’ imprimatur, it would be harder for critics to write them off. Eventually, a host of other federal agencies also got involved, including the ATF, DEA, and IRS. “There were two different objectives,” Kading explained as we sat around his poker table. “But they could intermingle.”

For the next few months, Kading set about collecting all the material from the Biggie investigation into a massive new case file. It was well over 100,000 pages. An entire wall of the task-force offices was devoted to a “murder map” connecting the players, witnesses, and evidence. Suspects and hypotheses abounded. “Our approach was like, everything is true,” said Kading. “All of these theories are potentially true until they’re disproven.”

The first avenue of inquiry to examine was Detective Poole’s. In his theory of the case, Biggie’s murder had been orchestrated by Suge Knight, the fearsome head of Tupac’s label, Death Row Records, in retaliation for Tupac’s death. Poole believed that Knight had hired a corrupt LAPD cop and his triggerman friend to do the killing. Kading called Poole’s explanation “simple and elegant.” The fact that Poole was a veteran detective who had dedicated his life and career to the department only added to the seriousness of his claims. “For many involved in the case, he became the ultimate whistleblower,” Kading wrote in Murder Rap. But as he began looking back at the details of Poole’s investigation, what Kading found simply didn’t add up. Despite all the speculation and publicity, no direct evidence was ever discovered connecting corrupt LAPD cops to Biggie’s death.

Instead, Kading and his colleagues turned their focus to the other prevailing theory of the case — that Biggie’s murder was a gang hit. In the ’90s, informants had come forward claiming that the Southside Crips had killed Biggie because Bad Boy Records, his label in New York, owed them money for security work on the West Coast. Others claimed Knight had hired his fellow Blood gang members to kill Biggie in retaliation for Tupac’s murder. Untangling the web of gang affiliations and street vendettas that appeared to connect both cases proved particularly challenging.

Kading spent weeks combing through old witness statements in an effort to establish a list of targets to re-interview, only to discover that nearly all of the people he identified turned out to be dead: Orlando “Baby Lane” Anderson, a Southside Crip suspected of multiple murders, had been shot to death outside of a car wash in May 1998; Alton “Buntry” McDonald, one of Suge Knight’s closest Blood allies, was shot in the chest at a gas station in 2002. “Hen Dog” Smith, “Poochie” Fouse, “Heron” Palmer, the list goes on — all murdered in drive-by shootings. “Just about every investigative lead had been exhausted,” Kading said.

The informants that remained seemed intent on throwing the investigation into turmoil. A former Crip named Michael “Owl” Dorrough claimed to know who had shot both Tupac and Biggie, but when members of the task force visited him in Pelican Bay prison he said he would only speak to Tim “Blondie” Brennan, an L.A. County Sheriff’s deputy detailed to the task force. Brennan’s former partner, Bob Ladd, says the insult caused a rift between the other officers that resulted in Brennan leaving the group. “They said they didn’t trust him,” said Ladd. (Brennan died in 2021. Kading said that Brennan’s departure was the result of a promotion, not the task-force dynamics.) Another informant, Robert “Stutterbox” Ross, sent agents across Southern California tracking down a drug runner he claimed was involved in Biggie’s murder, until Kading caught Ross on a wiretap bragging to friends that he had “a cop in his pocket” and was simultaneously running a bizarre scam to extort money from Shaquille O’Neal.

By that point, more than a year had passed and the task force had almost nothing to show for it. Cracks were beginning to form among the group. Kading wasn’t technically in charge, but he had essentially commandeered the task force, which frustrated some of the other members, who complained that he had refused requests to interrogate witnesses if he had already decided they were cooperative. Others said he compartmentalized the group, seemingly in order to maintain control. (Kading denies this, saying, “Everyone knew what everyone else was doing. If they didn’t, it was only because they had their head up their own asses.”) Mike Caouette, another former L.A. County Sheriff’s deputy, said that Kading’s management style could be infuriating. “I mean, we laughed, we had a good time, but in hindsight, several things happened and it really, really left a bad taste in your mouth.” Caouette told me that Kading was so obsessed with the notion that “Stutterbox” Ross was Biggie’s killer that he offered Ross immunity if he was willing to admit to the crime. According to Caouette, Ross’s lawyer was a friend of one of his partners and called him after a meeting between Kading and client to ask if a detective, not a prosecutor, making that kind of offer was “standard procedure.” Kading vehemently denies making the offer, and provided the minutes of his meetings with Ross to refute Caouette’s claims. He called them “ridiculous fucking bullshit.” Caouette called him “a pathological liar.”

Still, Kading and his colleagues did come to an agreement on the one target that was left to pursue: Duane “Keefe D” Davis. One of the few high-ranking gang members who had managed to escape the bloodshed of the ’90s alive and well, Davis’s name was all over the case file, from chatting up Biggie backstage at the Petersen museum on the night of his death, to his presence in Las Vegas on the night Tupac was killed. And against all odds, Davis was living prosperously in Southern California. Getting him to talk to law enforcement, however, wouldn’t be easy. For that, they would need leverage.

From his earliest days growing up in Compton, Davis had reveled in street life. “He was a little punk running around selling dope, trying to make some money like everybody else,” said Ladd, who patrolled the city for nearly 20 years. But after prison stints in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Davis returned to his old neighborhood with supercharged ambition, moving quickly up in the ranks of the Southside Crips, his neighborhood gang, until he was a shot-caller, one of the highest ranking members. According to Ladd, by the mid-nineties Davis was raking in millions of dollars a year running a drug trafficking network that was directly supplied by Colombian cartels.

When Kading punched Davis’s name into a DEA database more than a decade later, there was an immediate hit. Narcotics investigators in Richmond, Virginia, had already identified Davis as part of a cocaine-trafficking conspiracy that stretched across the country. Kading offered to work the West Coast half of the investigation with a simple goal in mind: Develop a strong enough drug case against Davis that he would be willing to divulge whatever he knew about Biggie’s murder in exchange for a deal.

Things moved quickly after that. Because the Biggie task force had been federalized, piggybacking on the DEA investigation in Virginia was relatively easy. Kading and his colleagues had access to wiretaps and informants, as well as funding for drug buys. They started buying kilos of coke from Davis through a South Side Crip informant who had done deals with Davis before. After a wiretap caught Davis boasting to a drug trafficker in Texas that he also sold “water,” drug slang for PCP, they started buying that too. Getting caught selling a single gallon jug was probably enough to put Davis away for the rest of his life, and, according to Kading, Davis had told the Texan, “Man, I can fill your swimming pool.”

We got everything we need on him, Kading remembers thinking.

In late 2008, Kading and Daryn Dupree, another LAPD detective on the task force, confronted Davis at his home in Southern California and explained the situation. Sitting in his garage so curious neighbors wouldn’t be alarmed, they told him he was looking at 20-plus years in prison on drug charges, not to mention harsh sentences for the numerous family members and friends who had been swept up in the sting. That is, unless he wanted to talk. About what? Davis asked. “Put it this way,” Kading told him. “We’re homicide investigators.” Within the hour, Davis’s lawyer called looking to discuss a deal.

For the first time in more than a decade, a leading figure in one of the gangs rumored to be involved in Biggie’s murder was willing to sit down for an interview. But the question remained: How much did Davis actually know? In an effort to extract the truth, the U.S. Attorney handling the case offered what’s known as a proffer agreement: Whatever Davis told them that day wouldn’t be used against him. In short, he was able to speak freely. In exchange, Davis could get potential leniency for the drug charges looming over him.

Faced with spending the rest of his life in prison, there was little for Davis to do except agree. There was only one problem. He claimed he didn’t know anything about Biggie’s murder. “That one wasn’t us,” he kept saying. But meetings kept getting scheduled and Davis kept showing up, so Kading figured he must have something else worthy of the proffer. A few weeks later, in early 2009, his suspicions were confirmed when he ran into Davis in the hallway outside of his lawyer’s office. “I don’t know nothing about what you want to talk to me for,” Kading remembers Davis whispering as they stepped inside. “But what I do know is gonna blow your fuckin’ mind.”

Back in 1991, Davis began telling Kading and his colleagues, he was introduced to a famed East Coast drug dealer and club owner named Eric “Von Zip” Martin during a pickup baseball game in Compton. Zip was a hustler extraordinaire who, according to Mike Tyson, once stole $600,000 of cash from boxing promoter Don King through sweet-talking alone. (Zip died in 2012.) Zip and Davis quickly struck up a relationship built mostly on cross-country drug deals, which eventually led to an introduction to another of Zip’s alleged associates, Bad Boy Records founder, Sean “Puffy” Combs.

With Biggie’s profile rising, Combs and his star artist were spending an increasing amount of time on the West Coast just as the rivalry between Bad Boy and Suge Knight’s Death Row Records was heating up. At the 1995 Source Awards in New York, Suge Knight had openly mocked Combs in front of a packed audience. A year later, Biggie and Tupac had come face to face in a standoff outside of the Soul Train Awards in Los Angeles, during which Tupac had implored Reggie Wright, Jr., the head of Death Row security, to “Shoot him, Reg! Shoot him!”

Davis claimed he offered Combs his Crip soldiers as security during West Coast tours. “Come on, we got your back,” he told Combs over the phone. “Just give me about 45, 50 tickets.” But according to Davis, Combs took the relationship one step further. During a stop on the 1995 Summer Jam tour in Anaheim, Combs allegedly told a hotel room full of Crip gangsters — Davis included — that he wanted “them dudes’ heads,” as Davis put it; i.e. for someone to kill Tupac and Knight. Combs may have simply been caught up in the moment; tensions were running high and he was by all accounts legitimately concerned for his safety. But later, Davis said, over lunch in L.A., Combs offered him a million dollars to get the hit done. According to Davis, he had agreed to the hit, telling Combs, “Man, we’ll wipe their asses out quick.” (Davis later told Kading he would have done it for $50,000.)

Kading and his colleagues were astonished. Had they heard that right? Tupac’s killing was a murder for hire? No, Davis replied. The trip to Vegas was meant to be a purely social one. Mike Tyson was fighting for the heavyweight championship that night and Davis had traveled there along with his nephew, Orlando Anderson, and a handful of other Crip associates to take in the spectacle. After arriving, they partied and drank champagne before heading to the MGM Grand arena where they watched Tyson dismantle his opponent, Bruce Seldon, in under two minutes.

It was then that the outing took a perilous turn. After the fight, Anderson briefly found himself alone in the lobby of the adjacent casino when Trevon Lane, a Blood gangster known for his connections to Knight, recognized Anderson as the Crip who had tried to steal his diamond-studded Death Row necklace during a scuffle at a mall a few months earlier. Rumors had been swirling on the street ever since that Combs was offering a bounty to anyone who could bring him one of the chains. Lane pointed Anderson out to Tupac, who was in town with Knight to watch the Tyson fight. Tupac rushed across the floor and asked Anderson, “You from the South?,” a reference to Anderson’s Southside Crip allegiance, then punched him in the face, dropping Anderson to the floor where he was set upon by a crew of Bloods. Davis was sitting in a nearby restaurant when word got back that his nephew had been attacked. “The shit became ominously personal,” he would later write in his 2019 memoir, Compton Street Legend.

Street code demanded that Anderson retaliate for the public beating, but because the visit to Vegas had been strictly social, Davis and his crew hadn’t brought any guns. That was where Zip came in. He had also arrived in Vegas for the fight and, according to Davis, offered up a .40-caliber Glock he had hidden in a secret compartment in his Mercedes-Benz. “He said it’s perfect timing,’” Davis recalled Zip telling him. For the next hour and a half, two cars’ worth of Crips staked out Club 662, a Knight-owned venue where Tupac was meant to perform, but the rapper never showed. Nearly giving up on the hit altogether, one of the cars headed home, leaving four in a white Cadillac that the entourage had rented for the occasion: Terrence “Bubble Up” Brown, the driver; Davis in the front passenger seat; and an associate named DeAndrae “Big Dre” Smith alongside Anderson in the back.

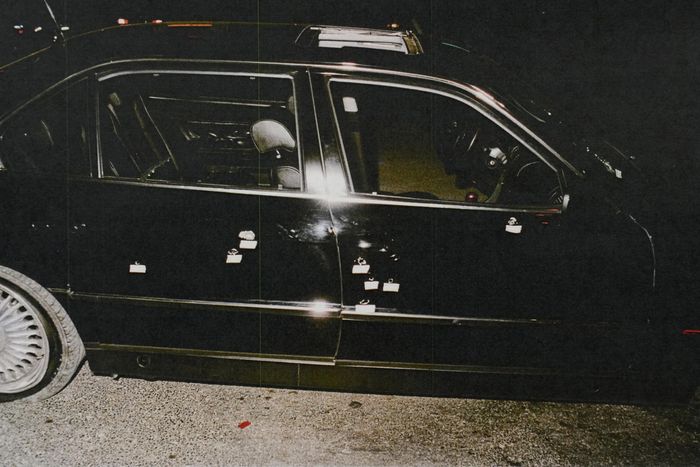

When Tupac didn’t show, they drove back toward the Strip on East Flamingo Road. Just after 11 p.m., Davis spotted Tupac up the street, near the intersection with Koval Lane, leaning out of the passenger side window of a black BMW that was being driven by Knight. As Tupac chatted up some girls in a passing car, Bubble Up hit the gas, sliding the car into the far-right lane, while Davis handed the Glock to Anderson in the back. As both cars slowed at the corner, Anderson reached across Big Dre and fired out the open window, hitting Tupac four times — two in the chest, one in the arm, and one in the thigh. He died in the hospital six days later. Knight, in the driver’s seat, was hit in the head by bullet fragments.

Kading instantly recognized how incendiary Davis’s story really was. Not only had he detailed the events behind Tupac’s shooting and confessed to his own involvement in the crime, he also laid at least part of the blame for the murder at the feet of Sean Combs. Davis claimed that soon after the shooting, Combs called Zip to ask, “Was that us?” Davis confirmed that it was and that, despite the personal nature of the killing, he still wanted his million-dollar bounty. He told Zip to handle the money on his behalf, but the payment never came. (Combs has repeatedly and vehemently denied any involvement in Tupac’s murder and has since called Davis’s claims “nonsense.” He did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

But any real sense of accomplishment was short-lived. Davis’s statements had already enticed Kading’s cop brain toward a new target: Combs. If what Davis was telling them was true, Combs was at the heart of a murder-conspiracy plot that had resulted in Tupac’s death. Just because they couldn’t use Davis’s statements against him in court didn’t mean they couldn’t use them to go after Combs.

A few months later, in June 2009, Kading, Dupree, and a DEA agent escorted Davis on a flight to New York City. The plan was for Davis to casually approach Zip Martin and rekindle their drug-trafficking relationship. “If we could catch Zip in the act of buying drugs,” Kading explained. “We could put the squeeze on him.” Perhaps then Zip would be willing to corroborate Davis’s story about the million-dollar bounty that Combs had allegedly put on Tupac and Suge Knight.

Over the next few days, Davis made multiple visits to Zip’s Harlem nightclub and, according to Kading, eventually made contact. He offered to cut Zip into a bogus drug deal he was working on, but Zip demurred, telling Davis he was sick and didn’t have the energy for “such a high-risk enterprise.” Zip did offer, however, to put Davis in touch with one of his associates, an introduction that would have tied Zip into a conspiracy charge if things got that far. Kading was pleased, he told me, and immediately began plotting the next phase of the operation.

As it turned out, however, there would be no need. Kading’s past was about to come back to haunt him.

Earlier that year, a grocery-store owner named Georges Torres, whom Kading had investigated on and off for years before joining the Biggie task force, was found guilty of 55 felony counts, including racketeering, bribery, and solicitation of murder. But rather than validating the efforts of the prosecutors and investigators who put the case together, the conviction quickly turned into a debacle. Within weeks, Torres’s defense attorneys appealed to the judge, claiming that there were fatal flaws in both the prosecution and Kading’s work on the investigation. Namely, that he had misquoted wiretaps and made improper deals for sentencing considerations and cash with at least two witnesses in exchange for their testimony, a similar criticism to the one allegedly levied against him by “Stutterbox” Ross’s lawyer.

The judge agreed. In a blistering, 147-page ruling, he wrote that “Detective Kading, had acted, at the least, with reckless disregard for the truth” and dismissed the bulk of the charges against Torres. Kading was later exonerated by an LAPD internal-affairs investigation, but the stain left behind by the allegations was difficult to erase. A month after Torres was let out of prison, Kading was called into a meeting with an LAPD commander and told he was being taken off the Biggie task force. “This is being done to protect you,” Kading remembers the commander saying.

It was a precipitous fall and one that left Kading embittered. He feared that without him, the task force would “wither and die,” a prediction that turned out to be correct. With Kading gone, his plan for Davis to ensnare Zip and Puffy fizzled out. Higher-ups in the LAPD decided to turn over the evidence Kading had developed to the Las Vegas Metro PD who rushed out to L.A. without understanding the context of the proffer. “They think they’re coming out to potentially arrest Keefe D who has confessed to the murder,” Kading explained. Despite having already been transferred to another division, he was dragged back into the task force offices to explain the situation. “They were a little chagrined,” he said of the Vegas officers.

Likewise, the hunt for Biggie’s killer, the task force’s actual assignment, also floundered. Around the same time that Davis was giving his confession, Kading and his colleagues had identified a woman named Tammie Hawkins as a potential conspirator in Biggie’s murder. Hawkins, who was the mother of one of Suge Knight’s children, had been involved in a number of criminal fronts on Knight’s behalf, and Kading believed she might know more than she was letting on. Faced with jail time and the threat of losing custody of her child, Hawkins told the task force that in 1997 Knight had enlisted her to act as a go-between in arranging a hit on Biggie in retaliation for Tupac’s murder. According to Hawkins, the shooter was Wardell “Poochie” Fouse, a Blood gang member who had died in 2003 after being shot ten times in the back while riding his motorcycle in Compton. “He had the mentality to do it,” said Ladd, who had once investigated Poochie for unloading a pistol on the car of a family driving past his house. But without further corroboration, there would always be doubt.

Kading was in the middle of requesting a wiretap on Knight when the Torres ruling came down. After he was pulled off the task force, one of his supervisors was asked by a reporter if the LAPD was close to catching the killer in Biggie’s case. “Probably not,” the supervisor replied. Soon after, the task force was officially closed. In 2010, Kading retired.

In a different world, the story might have ended there. Davis’s confession was protected by the proffer agreement, and Hawkins’s statements proved to be the death knell for the Wallace lawsuit, which was soon dismissed. With the task force shut down, neither investigation was moving forward. However, on his way out the door, Kading made a decision that would again rile his colleagues. He copied nearly the entire Biggie case file, dozens of boxes containing tens of thousands of documents. Like Russell Poole before him, he had decided to go public. “I couldn’t stand the idea of all our work going to waste,” he told me, though after some prodding he confided that the money he got from his book and media appearances hasn’t hurt either.

Kading wasn’t alone in publicizing the case. Since the early 2000s, a cottage industry of podcasts, documentaries, and YouTube shows has developed, each one promising to untangle the conspiracies surrounding the killings of Tupac and Biggie. The hosts and guests, many of whom are paid for their appearances, engage in constant squabbles and name-calling. When I asked Reggie Wright Jr., a frequent guest, whether he found the in-fighting tedious, he laughed. “I find it profitable if you want to keep it real,” he told me.

It may explain why Davis began making similar appearances around 2018. Perhaps he saw Kading and others profiting from the story he had told them and wanted a cut. He had also been diagnosed with cancer and may have seen his involvement as a way to shore up his finances. (Davis declined to comment through his lawyer.) Regardless, once he started talking, he held nothing back. In an interview for the BET series Death Row Chronicles, Davis publicly admitted to his involvement in Tupac’s murder for the first time. A year later, he described the killing in detail in his own memoir, Compton Street Legend. Whether or not Davis understood that the terms of the proffer only protected him for the 2009 interview remains unclear. Either way, he continued publicly confessing to the crime right up until the cops arrived at his house last summer.

Davis’s arraignment was delayed for weeks while he attempted to find a lawyer, eventually hiring a veteran Nevada defense attorney named Carl Arnold who devised a deceptively simple legal strategy: “He’s a liar,” said Arnold. Davis contends that he lied not only during the proffer agreement to Kading, but also in a follow up interview undertaken by Las Vegas police when they had arrived in L.A. to arrest him. He also lied during his appearances on the Death Row Chronicles TV show and in his own memoir. According to Arnold, prosecutors can’t even definitively place his client in Las Vegas on the night of Tupac’s murder. “Basically their whole case right now, from what I’ve seen, is just Keefe’s statements,” he told reporters. “If that evidence is all it is, we can walk into trial today. We’re walking back out. Not guilty.” Most defense attorneys struggle to demonstrate their client’s reliability; Arnold is hoping to do the opposite. The bigger liar a jury believes Davis to be, the stronger his chance of an acquittal.

But if Davis was merely fabricating a tall tale for the ages, then the statements he made to the task force in 2009 would necessarily be untrue, voiding the terms of the proffer agreement. The prosecutors trying the case could then enter it as evidence. When I asked Arnold if he plans to argue that Davis’s once-secret statement made to state and federal authorities a decade ago was also for entertainment purposes only, he laughed. “Keefe told them what they wanted to hear, so he wouldn’t have to go to prison,” he said. Moreover, Arnold welcomed the possibility. It would allow him to exploit what he considered an unexpected asset: Kading. “The idea was brilliant,” Arnold said of the drug case gambit that Kading engineered to ensnare Davis. “But the guy has no credibility whatsoever.” If prosecutors enter the proffer, Arnold would consider calling Kading to the stand. “He’s my Mark Fuhrman,” he said, equating Kading to the racist cop who undermined the case against O.J. Simpson.

The legal complications swirling around the case likely won’t be settled until the trial itself gets underway in November, but there’s also another question hounding Las Vegas authorities: Why now? Davis may have been the first person to offer a confession in Shakur’s murder, but similar stories of the killing have been circulating for years. A short time after Las Vegas detectives showed up in Compton wearing cowboy boots, they received an affidavit from Tim Brennan, laying out what he was hearing on the street about who was responsible. With a few minor exceptions, the story repeats almost exactly what Davis would tell authorities decades later. “The streets know before we know,” said Ladd, Brennan’s former partner. Why didn’t Las Vegas cops put more pressure on Davis and Anderson 27 years ago, especially if they had credible information that both were involved?

Based on Davis’s statements, the authorities in Las Vegas could also have pursued a case against Terrence Brown, the driver, before his death in a shooting in 2015, but failed to do so. And even after picking the case back up in 2018, they waited five years to indict Davis. It could be that, as Kading believes, prosecutors in Las Vegas were simply “feeding Davis the rope that he used to hang himself with.” The more confessions he offered, the more convincing the case against him would eventually be.

In hindsight, it appears that the singular chain of events resulting in Davis’s arrest unfolded in spite of the efforts of law enforcement, not because of them. Russell Poole’s hubris led to the doomed Wallace lawsuit, which led to a task force created to exonerate the LAPD for Biggie’s killing, which led to an unexpected confession in Tupac’s. And even having arrived at such a fortuitous destination, it was Kading’s ego and ethical breaches that brought the task force to an abrupt conclusion before he could pursue Davis’s allegations about Combs’s involvement. Still, the end of the saga appears to be nearing. Arnold thinks the November trial date will stick. “They’re stuck with murder,” he told me. “They couldn’t give us any offer that we would accept.”

Kading isn’t so sure. He thinks Davis will strike a deal with prosecutors before the trial. “They’ll give him a sweet offer just to put this thing to rest,” he said. “The whole thing will be anticlimactic.” I wondered whether Kading, after dedicating years of his life to unraveling the killings of Tupac and Biggie, would find such a resolution deflating, but he didn’t think so. He believed that despite all the controversy and convolutions, his efforts had revealed a decidedly uncomplicated truth: Tupac’s murder was an act of gang retaliation; Biggie’s, an act of revenge. “It’s the strangest paradox,” he told me. “Tupac Shakur’s case, and really Biggie’s too, at the very base of it, they’re just so simple.”