The passage of New York’s big, complicated state budget — every penny of the $237 billion the government plans to spend on your behalf over the next 12 months — is a portrait of power: who’s got the juice, who’s on the rise, and who got caught bluffing with a weak hand.

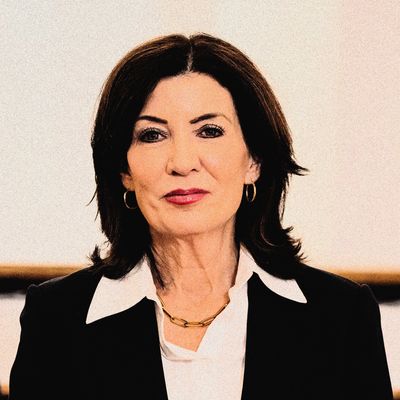

Governor Hochul clearly came out a winner, announcing victory and leaving town several days before the Legislature finished the budget. “This is a big deal — a very big deal. Everything that got done — the policy that we announced that I wanted to get done — my priorities in January are all in this budget,” she told me, holding up a big framed checklist of policies that resembled the menu in a 24-hour diner.

It seemed a little corny, but Hochul left no doubt that we are all playing by her rules now. And the No. 1 rule seems to be that you do not show weakness around this governor. In deal after deal, upon recognizing an adversary’s political problem, Hochul smiled — and drove one hard bargain after another.

Take housing. After two frustrating years of failing to get the Legislature to pass new tax credits that would give developers an incentive to build apartment complexes, Hochul, taking advantage of lawmakers’ desire to get out of Albany and back into their home districts to campaign for reelection, struck a complicated deal that tilts unmistakably in the direction of the real-estate industry, which has donated generously to the governor. Hochul’s allies in organized labor were well taken care of, too, with workers on new development projects guaranteed earnings between $40 and $72 an hour, depending on location.

By contrast, tenant advocates and their allies among left-leaning lawmakers got only a small degree of additional rent protections. Landlords who own only a few units, or whose buildings were erected after 2009, get an exemption from the new protections and, in many cases, will be allowed to raise rents by 10 percent.

“Housing took up 95 percent of our efforts for a very long time because there was so much we had to get done,” Hochul told me. “I was not going to leave until we built more housing.”

She stiffed Mayor Adams, who’d asked her to split the estimated $12 billion cost of caring for waves of asylum-seeking migrants to New York City. Instead of the $6 billion Adams asked for, Hochul and the Legislature gave a paltry $2.4 billion. And Adams, who is grappling with legal problems and low poll numbers, had no choice but to pronounce himself happy with the tiny sum, calling it a glass half-full (although 40 percent full would be more precise).

Hochul did help Adams by forcing skeptical lawmakers to give the mayor another two years of control over city schools, an important power that has to be renewed periodically. But even that came at a price: As part of the deal, Adams will have to build more classrooms and hire more teachers in order to meet the Legislature’s insistence on smaller class sizes.

Powerful Democratic legislators like State Senator John Liu, who chairs the committee on New York City education, wanted to deal with mayoral control later in the summer, but Hochul insisted on getting it done sooner. “As it turns out, the governor was very insistent on including this issue, and the governor has a great deal of influence during the budget-making process,” Liu told Chalkbeat. “So this decision-making was clearly rushed. It’s not best practice, but this is where we are.”

And so on down the line. Hochul didn’t want to raise income taxes on New Yorkers making more than $5 million a year; it didn’t happen. She wanted enhanced criminal penalties for shoplifters and got it done over the objection of State Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie. Hochul insisted on adding $19.5 billion to the state’s rainy-day reserve fund over the objection of health advocates and Democratic legislators who wanted to use the money to lower the cost of long-term care. And Hochul won passage of a controversial plan to eliminate state payments to hundreds of small companies that provide home health aides to patients on long-term disability; instead, New York will give the giant contract to a single company.

The governor’s victory lap showed less force but just as much swagger as we used to see from her predecessor, Andrew Cuomo, who would negotiate budgets by inviting top legislators over for a friendly chat and greet them with a plate of cookies and a baseball bat. Okay, maybe not a literal bat, but Cuomo swung his personality like a war club and was famously, ferociously intent on meeting the state’s April 1 budget deadline.

Hochul operates with a softer touch, inviting opposing groups in for conversation after conversation. On the mayoral-control fight, she told me, “we worked with the mayor’s office, the teachers union, the members of the Legislature, the advocates. I was doing a lot of convening, and my staff, we were around the clock on phone calls to say ‘Let’s get together and do this now.’” On housing, she says, “we were into the nitty-gritty in a way you would never believe.”

The consensus is that those secretive meetings were far less tense than in the Cuomo days. “Behind closed doors, I didn’t publicly castigate anybody. It’s not my style. But look at the results at the end; we delivered for New Yorkers and people who want to be New Yorkers,” she told me. “There are, of course, voices who are not thrilled. But you know what? I wasn’t here to please people; I’m here to help New Yorkers get a home.”