At an Apple event on October 4, 2011, the day before Steve Jobs died, Apple VP Scott Forstall took the stage to share details about Siri, Apple’s new voice assistant. “The exact words I say aren’t important,” he said as he asked Siri about the weather in multiple different ways. He asked it about stocks and “great Greek restaurants in Palo Alto.” He asked it to set a timer, give him driving directions, and create calendar events. He emphasized how it could “follow along in a conversation, just like a human does,” remembering what you’ve told it as it moves on to the next task. When it didn’t know answers, he said, it could search Wikipedia or tap into answer engines like Wolfram Alpha. “I’ve been in the AI field for a long time, and this still blows me away,” he said at one point during the presentation.

At the time, the demo was incredibly slick, suggesting wild and fantastic futures in which devices listened to us, understood what we were saying, and could handle a wide range of tasks on our behalf; earlier demos, released when Siri was still a DARPA-funded start-up, were even more optimistic, promising to make dinner reservations and call cars for drunk users. Upon wide release with the iPhone 4s, though, Siri was kind of a flop, and Forstall left the company within two years. Its interface and voice suggested human-style assistance, but what it delivered in practice was rigid, limited, and error-prone. Interactions beyond the first step tended to fall apart. Thirteen years later, the most notable thing about Apple’s early Siri demos is how little progress beyond them the company made over the next decade. It got a bit better in a wide range of quantifiable ways, but the company’s first ads for Siri remain basically accurate today. In 2024, for many users, Siri is still a kitchen timer, a weather app, and a tool for narration and transcription. Even the Siri parodies are the same.

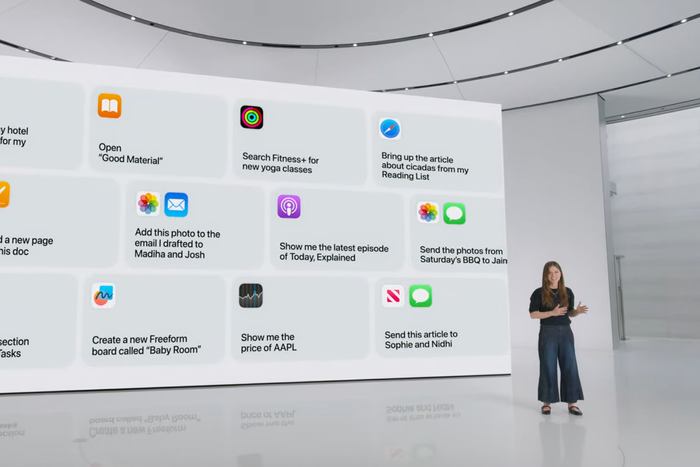

On Monday, at its big yearly software event, Apple showed off the next generation of Siri, powered by a new AI technology. The presentation was strikingly familiar. “Even if I stumble over my words, Siri will understand me,” the presenter said, echoing the original Siri pitch. She asked about the weather for an upcoming hike and talked about how the app could maintain “conversational context” to schedule it on her calendar. She asked it to bring up an article about cicadas from her reading list; she asked it to show her photos of a specific child in New York City wearing her pink coat. In 2011, Forstall asked Siri to pull up a stock index price; in 2024, Apple’s Siri presentation promised that users would be able to command Siri to, for example, “Show me the price of AAPL.” The presentation felt a bit like an apology. Apple’s new pitch was “Siri, but this time it works.”

After Apple’s event, AAPL briefly dipped — in part, perhaps, because Apple’s rumored big push into AI seemed relatively insignificant compared to some of its peers, feeding the industry perception that the new generation of AI tools exemplified by ChatGPT had taken Apple by surprise and that it was struggling to catch up. In truth, as Apple revealed to developers later that day, iOS 18’s integration of tools that might be described as “AI” — a loose and decreasingly useful marketing term — is fairly extensive and reflects intensive investment in a different vision of the technology under the banner of “Apple Intelligence.” Systemwide writing tools will offer to rewrite, proofread, and summarize text in most contexts; emails and notifications will be sorted and summarized; calls can be recorded, transcribed, and outlined; photos will be processed in such a way that they can be searched with plain-language requests; and users can remove entire people from photos with a few motions.

There were some constrained features for generating media, including an “Image Playground” text-to-image generator and a “Genmoji” tool. Apple’s rumored partnership with OpenAI turned out to be constrained as well: In some contexts, users will be able to ask ChatGPT to generate text; when Siri is unable to answer certain sorts of questions, users will be asked if they want to pass the request along to OpenAI through a system that Apple says will be open to other models as well, keeping the leading AI firm of the current generation at arm’s length.

In the superheated corners of the internet where AGI is imminent — or, in an increasingly common rhetorical shift, already here — this was underwhelming. OpenAI leadership is talking about the end of human labor and emerging superhuman intelligence, countless AI start-ups are promising “agentic” super-Siri assistants, and Google’s CEO is comparing AI to the discovery of fire. Meanwhile, Apple is relegating ChatGPT to a plug-in and giving its users a bunch of little utilities and widgets.

Another view is that Apple is merely being cautious, and with good reason. In 2011, it was easy to get excited about AI as it was defined and known then. Voice recognition alone felt magical, and Siri’s ability to parse a small range of spoken questions made extrapolation tempting and intuitive: If it can understand some things now, it will be able to understand many things soon; if it can usefully talk to some parts of my phone, which can interact with some real things in the world, soon it really will be a personal assistant. The fact that it had a voice, communicated in a conversational format, and told occasional jokes encouraged this line of thinking — a truly versatile Siri was just a short matter of time. In 2011, Apple was in a position not entirely unlike Microsoft is today, hitching the future of one of its most important products to a dazzling AI tool created by another company. There have been legitimate and huge advances in the field in recent years, and the range of tasks that software can assist with or accomplish on its own is expanding in every direction. But for those who were paying attention at the time, it’s worth remembering how magical it felt to talk naturally to a smartphone for the first time, the wild possibilities that it evoked — and what actually happened next.

Many of the largest companies in technology are indicating that they’re all in on AI, whatever they mean by the term, for which they’re being rewarded by investors. In the context of actual advances in the state of the art, Apple’s rhetoric is getting cooler. Its 2024 Siri presentation was, in context, far less ambitious than its 2011 debut. The closest the company has come to talking about AI like OpenAI, Microsoft, and Google are today was all the way back in 1987, in a marketing video about a theoretical “Knowledge Navigator.”

It’s worth watching this video in full for a few reasons. When it comes to hardware, it was fairly prescient: The video is set in 2007, the same year Apple ultimately introduced the touchscreen iPhone, soon followed by the iPad. It was likewise correct, directionally, about networked computers and the web. The virtual assistant promised here, however, is still struggling into existence. In the video, a bow-tied avatar helps deal with a busy schedule, reading the professor’s calendar and parsing his messages. This part is uncannily familiar — it’s how Siri was marketed the first time around. (In this scenario, as in 2011 demos, as in Monday’s demo, the assistant is helping to deal with a scheduled trip to the airport.) What happens next is familiar, too: The professor asks for an increasingly specific trove of information to plan a lecture about deforestation, drawing from the latest literature, narrowing down his data to specific regions, visualizing data, combining data in collaboration with another scholar, and summarizing a missed call from Mom. Avoiding calls from Mom is another recurring theme, here. In 2024, Siri is still saving us from talking to her:

The pitch for Knowledge Navigator is, and was, generic but enticingly intuitive. This is how personified computers had been represented in fiction for decades, as synthetic people, but at the time, the rapid pace of development in computing and networking encouraged forward extrapolation. AI, of a sort, had been a buzzy technology for years. After a period of massive government and private investment in promising AI technology, 1987 also marked the beginning of a long “AI winter,” a period of slowed investment and disillusionment that often follows periods of rapid development and heightened expectations in the field. Knowledge Navigator still doesn’t exist, but its fictional presentation matches, almost beat for beat, the marketing pitches for scores of LLM-powered tools that tech giants and start-ups are promising to bring to market soon. The ability of current AI chatbots to carry on something like conversations, and to generate a wide range of humanlike outputs, makes true personal assistants feel closer than ever — but then again, so did technology that allowed us to speak to software and for it to speak back. Maybe Apple really is just lagging behind, and what we saw on Monday is the best the company can do. Or maybe there’s some institutional memory there about the last time such things seemed closer and more inevitable than they actually were.

Apple Intelligence isn’t Knowledge Navigator, and Apple was relatively cautious about promising that it ever would be. For now, the company is leaving that dream to other companies, which are working on products that Apple customers can use through their phones, tablets, watches, and headsets. In another decade, perhaps these firms will have realized one of the tech industry’s oldest visions, bringing about societal transformation and untold riches. Or maybe, they’ll make a great deal of progress before their AI agents and personal assistants collide, once again, with the vexing messiness of reality. It’s a cautious approach by Apple, in the context of companies like Microsoft and Google. But it’s also a reminder that these companies are competitors but not quite peers. Whether AI development keeps accelerating or it slows down and fails to deliver, Apple can still expect to sell a lot of hardware.