This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In the fall of 2022, Molly Jong-Fast made a grave error, though only a select few would have noticed. The liberal pundit was hosting a book party at the Century, the private arts-and-letters club she’d joined during the pandemic, for her friend and fellow Centurion the media critic Margaret Sullivan. Jong-Fast was the subject of a forthcoming New York Times profile, and she allowed a reporter and a photographer to come to the party, which would ultimately become the leading anecdote of the story; a photograph from the event also made it into print.

Soon after it ran, Jong-Fast got a genteel slap on the wrist from the head of the Century’s board, who reminded her that the Century, wishing to keep its name out of the public eye, discourages any media attention. No photos, no public mention of the Century, and certainly no assisting journalists who might be trying to do the same. The only time the Century tends to be connected to a person’s name in print is in their obituary. Jong-Fast apologized profusely.

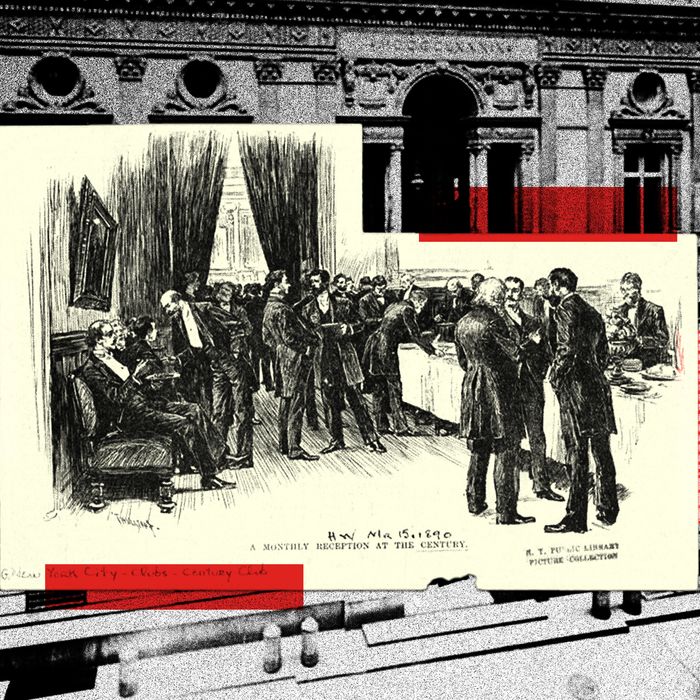

Despite the Century club — or association, as it calls itself — being media averse, the unmarked McKim, Mead & White five-story palazzo on 43rd Street has increasingly become the private club of choice for a certain class of journalists, particularly those from the Times, whose office is only a few blocks away. Among those who have joined in the past three years are executive editor Joe Kahn, opinion editor Kathleen Kingsbury, Pulitzer Prize winner Azmat Khan, and columnist Lydia Polgreen. Other relative newcomers include Columbia Journalism School dean and New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb, Atlantic CEO Nick Thompson, and MSNBC host Lawrence O’Donnell.

Journalists have always belonged to the Century, where Daily News editor Ed Kosner used to invite writers to lunch if they had published a good story. There are currently more than 50 media bosses, reporters, and editors who are members, including CNN CEO Mark Thompson, Times managing editor Carolyn Ryan, Vanity Fair editor-in-chief Radhika Jones, New Yorker articles editor Susan Morrison, New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast, author Robert Caro, Pushkin’s Jacob Weisberg, and CNN’s Fareed Zakaria. “There’s a definite irony in these journalists belonging to something you can’t talk about,” one member, who is a journalist, conceded. Put another way by a member who was deeply resistant to discussing the association: “Journalists expect the mother whose kid was just shot in the head to talk to a reporter. Yet the boss joins a group that he won’t talk to a reporter about.”

The Century has more than 2,000 members, and journalists make up merely a fraction of them, outnumbered by academics, artists, lawyers, philanthropists, architects, and other public-intellectual types. But in the post-pandemic years more journalists than ever are joining, as the Century, with its grand balconied Palladian window and marble columns, has once again become socially relevant in the media world, not only for members but for the many colleagues members can invite as guests. It has become a place to grab a drink with office mates (put it on the house account) or meet with an editor about a prospective job (just don’t make it look like you’re doing work in public, a no-no). Notably, many of the journalists who’ve joined the Century since COVID are in their late 30s and 40s — they are young, in other words, at least relative to the Century, where the median age, as of a few years ago, was around 71. “I’d only be young in the United States Congress,” one such newish member joked. For the past three years, Broadway producer and communications guru Alex Levy, who joined the club in 2022, has co-hosted a gathering for younger members in the fall, open to the roughly 5 percent of membership who are under 50.

That the place is getting younger is largely owed to the New Yorker’s Morrison, who, upon being elected to president of the club in 2016 — the first female president in its 169-year history — made a considerable push to diversify its membership: racially, economically, and generationally. Suddenly, events and programming were livelier (rock music!) and members were encouraging their younger friends to join and bring their friends, even if it meant they would be alongside mostly old people falling asleep into their soup in the corner of a mostly empty Gilded Age dining room.

And now that room is regularly humming, which speaks both to its evolution as the city has changed and how it has stayed the same. “It makes you feel like you’re part of something that’s been around for a while, which, coming out of the pandemic, when so many things closed, gives a sense of continuity,” one member said. “Something that I cherish is you’re in Times Square, it’s terrible, and then you turn east onto West 43rd Street, walk a block, and arrive at this unmarked historic building,” another member said. “You walk through the doors, and it’s like you’re in another century — and I’m not talking about the 20th century, either.” All of which is especially desirable amid the TikTok-ification of New York, where it’s increasingly hard to get a reservation, never mind a reasonably priced cocktail. At the Century, “drinks are like $9,” one member noted. “As everything in New York becomes so Instagrammable and optimized for that, it’s nice to go to a place that just isn’t.” Also, you always have a place to pee in midtown.

The media industry, too, has changed. “There’s a degree of nostalgia that newspaper people enjoy, and we’ve spent the last decade or more training ourselves not to say ‘newspaper,’ or talk about the front page, or luxuriate in all of the words and conventions of newspapering,” one longtime journalist said. “A membership at the Century kind of allows you to erase that boundary and be old school again.” The Century “also allows you to tell yourself that you’re a ‘belletrist,’ as if we’re all poets, when in reality we’re middle-management editors,” they added. “In a world in which there’s not a lot of chilled shrimp being served to journalists, it’s pretty nice to be able to go to the Century.”

Jong-Fast isn’t the first journalist to be reprimanded for bringing the Century into the public eye. In the fall of 1991, Frank Rich quit over an allegedly offending item that his wife, Times theater reporter Alex Witchel, had included in her weekly column — a mention of an upcoming play reading happening at the Century. Rich, then chief drama critic at the paper, soon received a call from a since-deceased member of the board. “He said, ‘You have to control your wife, and she should not be writing about the private business of the Century club in the New York Times,” said Rich. “And I quit.” What made it even more ridiculous, he noted, “is that the Century was then, on any given day, like the Times cafeteria.”

It has been this way for years, stretching back to the days when it was for men only. “Sometime in the late ’80s, Arthur Gelb” — the paper’s managing editor at the time — “came up to me in the Times newsroom in New York and very excitedly told me that we had to go to the Century Club for lunch because they were finally admitting women,” Times columnist Maureen Dowd recalled, noting Gelb and then-executive editor Abe Rosenthal, both members, frequently had lunch at the club. “So we went, with another woman who was a reporter at the Times, and we go through the door and some club employee comes rushing up to us waving his arms and calling out, ‘No, no, no!’ Arthur looked confused, and the man looked at him somberly and said, ‘Only one at a time.’ Arthur hesitated, thinking about which of his female companions could be jettisoned, before realizing, with a nudge from me, that we all had to leave — with asperity!”

The process of becoming a member still takes about as long as it does to have a baby. But in recent years, it’s gotten easier, with the association reducing the required number of letters of recommendation from ten to six. You can also now submit these letters online. “You can’t apply to the Century. You are nominated, or proposed for membership, basically by a friend who is already in,” one member told me. You need a “proposer” and a “seconder,” who then marshal together those letters of recommendation. “Then the committee of admissions considers you, and as they do, your name is posted publicly — like, literally in the lobby — and if anyone wants to offer feedback on your candidacy, they may.” Being a prominent journalist doesn’t make you a shoo-in; I heard that the Times columnist Pamela Paul was rejected last spring. (However, members I spoke to expect that she’ll reapply and have better luck this time around.)

Once you get in, there’s a onetime entrance fee (currently $5,300 for residents, $3,445 for nonresidents or members under 40), as well as annual dues ($3,920 for resident members; $1,960 for nonresident or sub-40 members.) “I think Soho House charges more,” one member noted.

The Century, unlike various university and members’ clubs around the city, does not have squash courts or a pool or overnight accommodations. Founded by artists in 1847, “its main activity is conversation,” as the website states. It is a place to read and drink — it has been called “the Drenchery” — and socialize and not be on your phone or computer. The idea is to disconnect from the outside world. It’s frowned upon to ask someone what they do for a living, what their last name is if they don’t offer it, and how long they’ve been a member of the Century. (Instead, ask, “How long have you been a Centurion?”) There’s no official dress code — the old line, according to one member, was “a gentleman doesn’t need to be told how to dress” — but the House Committee did send out a recent email, featuring an illustrated poem created by Roz Chast, to reinforce expectations (“Clothes for beach, clothes for gym / Not for her, not for him / Cut-offs, flip-flops, yuck and bad / Jeans with holes make people sad”).

The scene at the Century can thus feel like a reenactment of the 1990s. Levy and Jong-Fast rent out one of the dining rooms periodically to host salon-style parties for a rotating cast of nonmembers — though many have since joined — with past media guests including Maggie Haberman, Ben Smith, Taffy Brodesser-Akner, and Don Lemon. “The food is bad and the service worse, but then every meal I’ve ever had there goes on someone else’s house account, so I’ve never paid a cent,” said one under-35 reporter. “And it’s actually cool in there. The place has a kind of dusty glamour, it’s a real time warp, and there are always some interesting characters walking about — big-shot writers and editors and novelists.”

The Century’s signature cocktail is called a Silversmith, which is essentially a rum sour served always, one member assured me, on cracked ice. It comes in a silver cup, each of which has a dead Centurion’s name on it and has been purchased by that person’s friends. You might get Ralph Ellison’s cup or Franklin D. Roosevelt’s or Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s or Brooke Astor’s — Jackie O. and Astor were among the first 20 women to join the club when it started admitting them in 1988. But more often you’ll get the lesser-known Centurions because, as one member told me, people steal the good ones and take them home. (Another member had a hard time believing that: “I don’t think a Centurion would steal a Silversmith cup.”)

The only time each month that members are not allowed to bring guests is during the monthly members’ meeting, a black-tie affair that last week was attended by some 400 members. After hors d’oeuvre, you make your way up to the table you’ve hopefully been invited to; if not, you can sit at the long communal table. You’ll eat some dinner — maybe chicken cordon bleu or, most recently, short ribs — before a bell rings and members go down for the meeting, which features a lecture and the ceremonial lighting of a torch. Around 10:30, most people shuffle out, while those with more in them head down to the Billiard Room. This month, in the Billiard Room, there will be a discussion about “the history of waacking,” a street dance style born in the underground gay clubs of Los Angeles in the ’70s.

On any given night, various committees put on events. The Committee on Music this month is presenting a concert devoted to the music of Otis Redding and the Allman Brothers. The Century Book Club is kicking off the year with War and Peace. And a “Twelfth Night” celebration featured, according to the monthly Century Bulletin newsletter, “an original musical farce, traditional pageantry, Beefeaters carrying the Christmas pig, and the holiday fare of Chef Jean Claude. Dress is black tie, but attendees are encouraged to come costumed in classical Roman attire or as you like.”

But mostly it’s just a nice place to go sip a martini — careful, though, as the Century’s is “more martini than you’ve ever encountered in your life,” as one member put it — and engage with other learned people in a sprawling library packed with every periodical you can imagine, the same one where Newland Archer would read the afternoon papers in The Age of Innocence. “It’s very writerly and a bit threadbare. It’s not like going to Casa Cipriani downtown, with its lacquered walls and fine mohair settees,” another member said. “The Century is kept in reasonably good repair, but there’s something transporting and comforting about its imperfections. It feels like a liberal-arts college. When things start to fray, rather than replace, they restore. I once saw a photo of the Century from 1910 and was like, I sat in that chair last week.” As one journalist who is thinking of joining told me: “I just need a place where I can gather in real life with fellow mildly reactionary middle-aged people.”

More From This Series

- How Trump Is Dividing and Conquering the White House Press Corps

- The Washington Post’s Strategy Is to Do Whatever Jeff Bezos Wants

- The Media Is Now Part of Trump’s War Against the Deep State