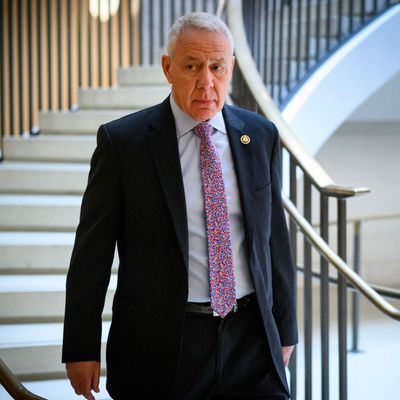

The news that Colorado congressman Ken Buck is abruptly resigning from Congress is a development with potential ripples. It lowers Mike Johnson’s GOP House majority to a spare two votes, at least temporarily. It could complicate the attempted survival strategy of celebrity MAGA weirdo Lauren Boebert, who will now have to navigate a special election to fulfill her ambition of switching districts to Buck’s more Republican stomping grounds. And it eliminates from Congress one of the very few House Republicans left willing to call b.s. on Donald Trump’s lies about the 2020 presidential election — and also to object to the House GOP’s impeachment mania.

But Buck’s departure might also make you feel old, if you remember his reputation when he first gained national renown in 2010 as a U.S. Senate candidate.

Right now, he’s the sort of all-purpose dissident who makes journalists wonder if he’s about to launch a centrist independent political career:

But during his Senate campaign, Buck was considered the hardest of hard-core Tea Party conservatives in his battle for the Republican nomination against Lieutenant Governor Jane Norton, as The New Republic noted at the time (full disclosure: I was the author of the piece):

Buck, famous for spearheading a crackdown on employers of illegal immigrants, developed [a lot of] steam among Tea Party loyalists and other conservatives…. He picked up national support from Jim DeMint’s Senate Conservatives Fund and RedState’s Erick Erickson. By late June, he was in the lead.

Ken Buck made his first gaffe at a strange venue: the annual Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms Party sponsored by a Colorado libertarian organization. In the midst of discussing one of Jane Norton’s ads, which questioned whether Buck is “man enough” to criticize her directly instead of relying on third-party groups, Buck said: “Why should you vote for me? Because I do not wear high heels.” He went on to characterize his own cowboy boots as having “real bullshit on them,” as opposed to political bullshit.

He narrowly won the nomination, but then, in that fabulous year for Republicans everywhere, lost in a close race to appointed Democratic incumbent Mike Bennet, after again sounding like a troglodyte, as Politico reported:

Colorado Republican Ken Buck stood by a pair of controversial statements Sunday during a shaky nationally televised debate with Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet.

Pressed by “Meet the Press” moderator David Gregory, Buck said he believed that being gay was a lifestyle choice and expressed no regrets about his four-year-old characterization of an alleged rape as “buyer’s remorse.”

Four years later, he was still considered a figure of the hard right when he hopped into a safe Republican House seat opened up by Cory Gardner’s successful Senate run. And he hasn’t really changed, toting up a 91 percent lifetime rating from the conservative litmus test administrators of Heritage Action, with particularly right-wing views on abortion, guns, and climate change. Despite his much publicized differences with Donald Trump, which we’ll get to in a minute, he voted with the Trump administration 87 percent of the time during the 45th president’s tenure in office. And he was a staunch member of the House Freedom Caucus, notably joining its most intransigent faction in voting to eject Kevin McCarthy from the speakership because of his “broken promises” to cut federal spending.

But Buck drew the line on the non-ideological issues of Trump’s 2020 election denial, which he opposed, and the constitutional standards for impeachment, which he insisted were not met by House Republicans seeking to impeach Joe Biden or his Homeland Security secretary, Alejandro Mayorkas. He also stood out for refusing to promise to support Trump’s candidacy in 2024 if the former president is convicted of a felony.

In self-isolating from his Republican colleagues and then leaving Congress in a huff, Buck is a poster boy for the radical change in American conservatism since Donald Trump came to Washington. He really hasn’t changed, and seems to be the same reactionary he’s always been. But in an ideological movement and party defined by one man, his independence of that one man was enough to send him into the political wilderness.