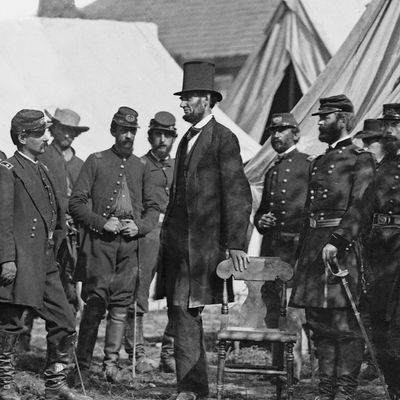

The United States is in a period of mostly nonviolent civil conflict that erupted into insurrection on January 6, 2021, and remains highly dangerous. One of the few political issues that unites most Americans these days is our shared horror over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which may be the biggest threat to global peace and stability since the end of the Cold War. At this fragile moment, journalist John Avlon has published a fascinating book, Lincoln and the Fight for Peace, that offers lessons from the 16th president about how to manage and transcend conflict without abandoning principle. I had a conversation with Avlon about his book and its current relevance.

As your book notes, Lincoln is one of the most discussed, written about, admired, and analyzed presidents in history. What drew you to his specific strategy for promoting peace and its echoes in later American history?

Years ago I read a quote from an American general named Lucius Clay who oversaw the occupation of Germany after World War II. He was a Southerner born 30 years after the Civil War, son of a three-term U.S. senator from Georgia. When asked by a reporter what guided his decisions, which by all accounts had worked out pretty well, he said, “I tried to think what Abraham Lincoln would’ve done for the South, if he had lived.”

Lincoln’s plan to win the peace after winning the war, which he never got to implement, is a topic that has been under-covered. But there is evidence that his vision was vindicated generations later, after the Second World War. The core of his vision was unconditional surrender, followed by a magnanimous peace.

Much of the discussion of your book has revolved around your suggestion that Lincoln’s strategy has implications for our current domestic situation, in terms of partisan and ideological polarization. Does someone have to “win” today’s conflicts (we devoutly hope without violence) before we can begin working toward peace?

One of the things the Civil War teaches us is that we’ve been through far worse divisions before. The ideal of “a more perfect union” is something we can only approximate. Our progress toward true majoritarian and multiracial democracy has been fitful at best, and has been bitterly and sometimes violently resisted. There’s a core of demographic panic, frankly, that motivates the desperation of the elites posing as populists. That was true during the secession crisis and it’s true now.

Thinking of the Civil War and its aftermath as the story of our “second founding” is the kind of shared history that can help reunite us as a nation, a sort of grand reset. I call Lincoln a “soulful centrist” because he set about winning the peace by empathizing with opponents as a means of reasoning with them — by focusing on achieving great goals, but being open to negotiation on the details of how those goals are achieved. Even in the middle of the Civil War, he didn’t demonize people he disagreed with. His honesty helped build trust; his humor disarmed opponents; and his moral humility made it possible to negotiate in good faith.

It’s the politics of the Golden Rule, treating people as you would like to be treated. Sadly enough, that retains the force of revelation. We don’t see it in our politics. It was rare in Lincoln’s time as well. He’s bookended by two of our worst presidents, who lacked both empathy and principle, not to mention vision. There are times where the gradualism of Lincoln has a grandeur to it because he was trying to achieve sustainable change.

I’m old enough and southern enough to remember when the conventional wisdom was that President Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor, followed his vision for post–Civil War America. You describe Johnson in a chapter headline as “the anti-Lincoln.” Could you elaborate?

Andrew Johnson is an object lesson in the great truth that character is the single most important quality in a president. He and Lincoln were opposites in fundamental ways, despite their humble upbringings and the fact that they’d served one term in Congress together. Johnson was a man who was motivated by resentment and grievances and perceived slights, whereas Lincoln was a reconciler and a temperamentally moderate man. That made all the difference.

Johnson immediately tried to stop any progress toward equal rights, let alone a multiracial democracy, which were both central to Lincoln’s vision (though he knew it would take time). Johnson seemingly delighted in giving amnesty to Confederate leaders and the planter class. The fact that the Black Codes were put into place by Confederate generals serving as acting governors of southern states as soon as the late summer and fall of 1865 had repercussions that lasted for a century.

And all that was done with Johnson’s blessing. He vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. He tried to dismantle the Freedmen’s Bureau and restore much of the planter class’s power while resisting Black rights and equal rights. Radical Republicans fought back, and the country was set on a path where the peace was lost rather than won. Ultimately slavery was replaced by segregation.

There is an intermediate step in Lincoln’s strategy, between surrender in war and magnanimity in peace, where he insisted on accomplishing the core goals of the war; an unprincipled victory wasn’t enough. The problem with Jackson is that he sought to simply return the country to the pre-war status quo, minus slavery. He was willing to abandon the war aims that Lincoln articulated in his Second Inaugural Address.

The famous last paragraph of that address, which exemplifies New Testament leadership, as I’ve called it, is a road map to reconciliation. But the rest of the 701-word speech is very Old Testament, calling for collective punishment for the original sin of slavery. There’s no moral equivalence to the North and South, though Lincoln does make it clear that the North was complicit in tolerating slavery.

The whole essence of Lincoln is combining strength with mercy. He understood that there needs to be truth and accountability before there can be reconciliation, but he was very conscious that if you go too far, too fast, you risk backlash. He aimed at sustainable progress.

You argue that World War II, and the post-war recovery of Europe and Japan, almost perfectly echos Lincoln’s strategy for winning both war and peace. But since World War II, the United States has not decisively won its military engagements (other than, arguably, in Kosovo). So is there some sort of Lincoln strategy for less-victorious wars? Or is the point that you shouldn’t wage war unless you know you can win, which I think some people refer to as the Powell Doctrine?

I think Lincoln understood that people are more likely to listen to reason when they’re greeted from a position of strength. You get further with a kind word and a gun than a kind word alone. You need to win on the battlefield. You need to win the 1864 election for any peacemaking effort to matter.

Lincoln’s strategy is not a cookie cutter that can be applied to every conflict. But it does reflect a broad set of principles that work, particularly a willingness in the middle of a war to envision a postwar regimen based on reconciliation rather than revenge.

Lincoln’s approach was relevant in other important ways, too. We are realizing belatedly that we cannot take our own democracy for granted. The Civil War generation left us a series of tools to deal with insurrections. But as in other contexts, Lincoln gave us an approach that requires empathizing with your opponents as a means of reasoning with them. It’s an important skill.

One way to project strength and simultaneously reflect your values is through alliances, international agreements, and other compacts based on principle. As you point out, after the reconstruction of Europe and Japan following World War II, that became the cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy (along with anti-communism). The U.S. articulated universal liberal principles that everyone can subscribe to, and that in theory treat all countries equally, while representing a distinctly American point of view.

We’ve gotten away from that approach partially because the Cold War ended and the Iraq War failed — but also because of the rise of sort of a new isolationism, or maybe Jacksonism in foreign policy. Is a return to efforts to project our values and project strength through alliances rather than unilaterally threatening military force a Lincolnian thing to think about?

What we’re confronting now is simply a drift back to the idea that might makes right. Lincoln as a lawyer and a statesman believed the opposite, that right makes might, which means not compromising on great goals and principles. He had a lot of people in the North begging him to accept a cease-fire in the middle of the Civil War, but he refused to consider a cease-fire before unconditional surrender. He believed that if you didn’t remove the root cause of the war, you’d just get committed to another war down the line.

So the unilateralism that America has unwisely pursued primarily under Republican presidents in the recent past is a repudiation of our best liberal democratic traditions, which presidents of both parties embraced during World War II and immediately thereafter. This is one of America’s great gifts to the world. And it’s a direct reflection of our commitment to winning the peace, which included the Marshall Plan, the creation of NATO, and the development of the outlines of trade agreements that created interdependence even between former foes.

People forget that the Marshall Plan was based on a bipartisan agreement that was difficult but essential to achieve. It was obviously led by President Harry Truman working with George Marshall, his secretary of State, but it also depended on the support of Republican senator Arthur Vandenberg, a former isolationist. He took plenty of slings and arrows from his far right. But this Republican involvement made the Marshall Plan better and above all more sustainable.

We’re now beginning to understand that we’ve taken 75 years of relative peace and prosperity in Europe — not the historic norm at all — for granted. But if your sense of history is only what’s in sight, then you’re kind of ill-equipped to deal with the real dangers of people who are trying to erode these international institutions that were put in place by America and its allies after the Second World War. The difficulty and fragility of this effort is shown by what happened at the end of the First World War, where President Wilson failed to get an unconditional surrender before cease-fire, and then the Allies sought reparations without the will to enforce them. It produced the worst of all worlds.

Vladimir Putin has reminded us there are always people who believe that might makes right. This is the cult of the strongman. This is the siren song of authoritarianism. And we’ve dealt with these dynamics before. We saw them in the 1930s, when democracies were divided and many felt autocracies would be more efficient. Stopping a drift in that direction requires that we defend international institutions, stand up to authoritarians, and rebut the inevitable rationalizations for acquiescing to evil. And it is an evil. When the war in Ukraine ends, no matter how it turns out, we will likely again have to win the peace, with an intensity resembling Lincoln’s.

At least we have the example of Lincoln and those who applied his principles in the past. Lincoln himself had to envision something that hadn’t previously existed. He wasn’t able to pull a book off the shelf.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.