There he was, on what figured to be one of the most important days of his criminal trial in Manhattan, sitting not 20 feet away from the witness he recently described as “death.” The jury had just heard Donald Trump’s unmistakable voice, on tape, suggesting that he pay off a secret debt “with cash.” Michael Cohen, his former attorney, was explaining how he had decided to surreptitiously record his boss, creating the hardest piece of documentary evidence tying Trump — who is famously averse to communicating in writing — to a series of “catch and kill” deals with tabloid executive David Pecker, a man Cohen referred to on tape, gangland style, as “our friend David.”

“Why did you think it was a bad idea [to pay] in cash?” asked prosecutor Susan Hoffinger.

“I believed that the proper way to do it would be by check,” Cohen replied, “and make it appear to be a proper transaction.”

As the witness parsed his incriminating words for the jury, Trump made sure everyone in the courtroom could see his mind was elsewhere. He was ostentatiously reading from a sheaf of papers he had carried with him into the courtroom. He plucked up the next page and leaned back in his chair, allowing me to catch a glimpse of a familiar set of red and blue bar graphs. It was the latest New York Times poll of battleground states. Before coming into court in the morning, Trump had waved the Times story accompanying the poll in front of reporters in the hallway, saying it “shows us leading everywhere by a lot.” Up by three in Pennsylvania, seven in Arizona and Michigan, ten in Georgia, 12 in Nevada. “I think we’re leading in New Jersey,” Trump said, citing as evidence the size of his rally over the weekend in Wildwood.

Let the star witness testify, Trump seemed to be saying. He was winning where it mattered.

Trump had entered the courtroom that morning with a larger-than-usual entourage, which included his son Eric and a pair of senators, Tommy Tuberville and vice-presidential hopeful J.D. Vance. Cohen, by contrast, looked gaunt, jowly, and nervous, taking visible deep breaths on the stand. In a deliberate monotone, he described how he had become Trump’s designated bully and then his betrayer. There were no bombshells: The details were by now familiar to anyone who had attended the trial or just followed politics during the Trump era. “I’ve been here for 26 minutes and I’m about to fall asleep,” Vance live-tweeted from his seat in the second row behind the defense table, saying it was ridiculous to criticize Trump for dozing, as he seemed to be doing again at times yesterday. After lunch, a member of the public in the gallery was observed to be audibly snoring.

Who would have thought that on the stand, Michael Cohen would be … boring? But the lack of excitement was a sign that the prosecution had done its job well. For the most part, Cohen’s testimony was corroborated by evidence presented through earlier witnesses. They had uniformly described him as an untrustworthy, hyperactive goon. Cohen admitted under oath that he had lied and played the heavy — but only in the service of “the Boss,” as he called Trump. “The only thing that was on my mind,” he said, “was to accomplish the task and make him happy.” Cohen said he had vague responsibilities and reported solely to Trump. Their cell phones were synced so that he could access the Boss’s contacts. (They had more than 30,000 together.)

When Trump decided to run for president, in 2015, Cohen said Trump told him they had to be prepared because “there’s going to be a lot of women coming forward.” The first was Karen McDougal, whose story came to them via Pecker, the publisher of the National Enquirer and a longtime friend and ally of Trump’s. Cohen testified that when he alerted the Boss, the response was “She’s really beautiful.” Cohen and Pecker together arranged to buy McDougal’s story and take it off the market, never to be told. Cohen testified that he was present for a phone call in which Pecker had told Trump the price was $150,000. “To which Mr. Trump replied,” Cohen testified, “‘No problem, I’ll take care of it.’”

Cohen said that he had arranged to repay Pecker’s company and to have the rights to McDougal’s story transferred to a newly formed shell company. But the Boss, as is his lifelong habit, was not quick to pay, and Pecker complained loudly that the $150,000 was not something he could easily hide on his balance sheet. (The going rate for tabloid stories, he and others testified, was much lower — in the range of $10,000.) Cohen testified that in order to reassure Pecker that he would be paid back, he decided to walk into the Boss’s office with his iPhone in his hand and voice-memo app recording. That is how a garbled and oblique conversation came to be played in court in which Trump appears to acknowledge his awareness of the deal. Ultimately, however, for reasons of his own, Pecker got cold feet and backed out.

“He told me to rip it up, forget it,” Cohen testified. Trump’s reaction, he said, was “Wow, that’s great.” He didn’t have to pay anything, and the Enquirer would still sit on the story.

Cohen’s version of events broadly lines up with Pecker’s earlier testimony, but there were notable contradictions. Pecker testified that Trump was at first resistant to pay hush money and that it was Cohen who had called him back later to say to go ahead with the deal. The defense, which should begin its cross-examination tomorrow, is certain to accuse Cohen of minimizing his own role as the primary orchestrator of the plot. But the prosecution did an able job of showing, in painstaking detail, how each of the beats of Cohen’s stories were backed by contemporaneous texts and phone records, including multiple phone calls with Trump around the time the deals were struck.

It was particularly interesting what the phone records did not show. Contrary to what Cohen represented to others, he and his Boss were not in constant contact. Though Trump is known as a constant telephone gabber, between early June 2016, when the McDougal matter arose, and early October 2016, when the Access Hollywood tape came out, shaking up the campaign, phone records produced by the prosecution show only four calls between them. This makes it all the more damning, in the prosecution’s telling, that there was a flurry of phone calls between Trump and Cohen, and between Cohen and Trump’s retinue (his communications director Hope Hicks, his bodyguard Keith Schiller), in the final stretch of the campaign. Trump was flying all over the country, trying to win the presidency, yet it seemed he had the time to talk to Cohen about something. That something, the prosecution alleges, was Stormy Daniels.

Cohen said he first learned that the porn star was trying to shop a story in the days after Access Hollywood tape appeared in October 2016. He had first heard about her account of a sexual encounter with Trump five years before, when a rumor about it had appeared in a (quickly taken drown) item on a gossip website. He testified that he had asked Trump if there was any truth to it and that Trump had replied, once again, that Daniels too was “a beautiful woman.” Trump said that they met at a celebrity golf tournament in the company of Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger. Trump remarked to Cohen that it had heartened him to see that “women prefer Trump even over someone like Big Ben.” Trump’s reaction to the rumor’s reemergence in 2016 was less sanguine.

“He said to me, ‘This is a disaster, a total disaster,’” Cohen testified. “‘Women are going to hate me. Guys may think it’s cool, but this is going to be a disaster for the campaign.’” Cohen said that he asked Trump whether he worried about his wife’s reaction. “He goes, ‘Don’t worry. How long do you think I’ll be on the market for? Not long.’ He wasn’t thinking about Melania. This was all about the campaign.” This part of his account seemed to catch Trump’s attention. He scowled, scribbled something on a legal pad, and pushed it toward his lead attorney, Todd Blanche.

Then Trump closed his eyes again.

Cohen said Trump’s plan was to do a deal with Daniels to buy the rights to her story but to delay payment until after the election. “If I won, it won’t matter because I’m president,” Cohen said, summing up the Boss’s attitude. “And if I lose, I don’t really care.” But Daniels was not stupid. On October 17, after Cohen delayed on paying her the $130,000 he had promised in return for her silence, she had her lawyer send an email threatening to rescind the agreement. Cohen was informed she had an offer from the Daily Mail. He placed an eight-second phone call to Trump.

The next morning, Cohen received a text message from Melania, who was helping to coordinate the response to the Access Hollywood tape. (She was the one who came up with the locution “locker-room talk,” Cohen testified.) “Can you please call DT on his cell,” Melania wrote.

Cohen testified that Trump said he had talked to some unnamed “friends” who were “very smart people” and who had told him that he was a billionaire and he should just give up and shell out the $130,000. Cohen said that was his signal to go ahead. Still, there was the problem of finding the money. The Trump Organization’s chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, allegedly tried to come up with creative ways to pay Daniels without creating a paper trail that went back to the company. Maybe Cohen could find someone who wanted to join one of Trump’s golf clubs and divert the joining fee to Daniels. Maybe someone was putting down a deposit for a bar mitzvah. Ultimately, the two men decided that one of them would have to front the money and rely on Trump for repayment. Cohen asked Weisselberg to do it, but he said he didn’t have the cash. So Cohen took out a home-equity loan.

At crucial junctures that October, prosecutors showed calls between Trump and Cohen. They talked twice on the morning of October 26, as Cohen testified he was walking to the bank to open an account that he would use to funnel the money to Daniels via her attorney. “I wanted to assure that he approved of what I was doing,” Cohen said. “Everything required Mr. Trump’s sign-off. On top of that, I required the money back.” And there, as always, was the rub.

After Trump’s election, Cohen said he knew his job at the Trump Organization — where he served the Boss alone — would come to an end. He testified that the incoming White House chief of staff, Reince Priebus, had offered him a position of assistant general counsel in the White House. He didn’t want it. He testified he had hoped to be considered for Priebus’s job and found it “disappointing” that he wasn’t even in the running. Trump shook his head a little at that. “It was more for my ego than anything,” Cohen said.

Other witnesses have testified that Cohen was despondent, or even suicidal, after coming to the conclusion he wouldn’t go to the White House. He testified he wasn’t that despondent. As an alternative, Cohen said he set his sights on carving out a special role as “personal attorney to the president.” He saw this as a “hybrid” job that would allow him to maintain his ties to Trump while also offering “consulting” for clients who wanted to understand the mind of the new president. “Mr. Trump was an enigma,” Cohen said. “No one knew what his feelings were and what his positions were.” Under questioning, Cohen admitted that he saw this as an opportunity to “monetize” his connection to the White House while continuing to represent Trump as a lawyer for free.

Cohen’s delusions of influence-peddling grandeur were dashed, however, at the end of that year, when Trump’s assistant Rhona Graff came around the office with everyone’s annual bonuses, which were traditionally inserted in a holiday card signed by Trump and other top executives. When he opened the card, Cohen said, he was shocked. Trump had cut his bonus by two-thirds. “I was truly insulted, personally hurt by it, didn’t understand it, it made no sense,” Cohen said. He was on the outs. He barged into Weisselberg’s office to protest. “I was, even for myself, unusually angry.”

Trump listened to this account of his alleged perfidy with the hint of a smile. Then he went back to reading and making notes on a stack of printouts of supportive quotes from J.D. Vance and others.

Finally, at the end of the day, Cohen came around to the heart of the criminal case: his reimbursement. He testified that Trump understood he was angry and called him over the holidays to smooth things over. He promised to work things out with him so that he received a fair bonus and got back the hush money he had fronted. He and Weisselberg sat down with a bank statement that showed the $130,000 bank transfer. The chief financial officer said that he wanted to classify the payments to Cohen as compensation, allegedly for purposes of disguising the payment’s purpose, and for that reason doubled the reimbursement to cover income taxes. He scratched the words “grossed up” on the statement and came to a total of $420,000.

When the conversation was over, Cohen said, they went to go see the Boss. It was just days before the inauguration, and Trump was taking care of unfinished business as he prepared to leave for Washington. “He approved it,” Cohen said. “He said, ‘This is going to be one heck of a ride in D.C.’” In paying off a malcontented, jealous, soon-to-be former employee, you can imagine Trump thought he was neutralizing a risk and closing the books on his dirty old life. All these years later, he finally may be undone by his grudging decision to pay a bill.

More on Trump on trial

- Why Michael Cohen Still Misses Donald Trump

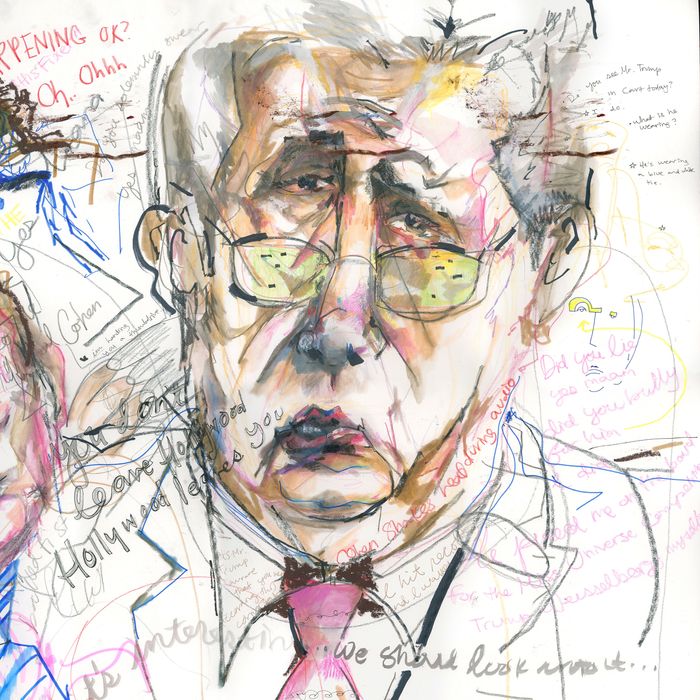

- What It Was Like to Sketch the Trump Trial

- What the Polls Are Saying After Trump’s Conviction