In 1998, a prematurely silver-haired, baby-faced priest named C. John McCloskey was dispatched by Opus Dei, the secretive right-wing Roman Catholic group, to Washington, D.C., to minister to some of the world’s most powerful men. He arrived at the Catholic Information Center, which the organization runs, on K Street, the lobbying district of the nation’s capital, to act as a kind of lobbyist for the nation’s soul. Before being ordained, the priest had spent a few years on Wall Street at Citibank and Merrill Lynch. And even after taking his vows, he retained his dealmaker’s personality.

From his office at the CIC (which bills itself online as “the closest tabernacle to the White House … providing sacramental access to busy Washingtonians for seven decades”), to the capital city’s private clubs and white-linen restaurants, McCloskey — known to the flock as “Father John” — set about networking. In a few years, he succeeded in converting some of the most influential American conservatives of his time, among them Robert Bork, columnist Robert Novak, Kansas senator Sam Brownback, Larry Kudlow, Newt Gingrich, as well as lesser-known figures like right-wing publisher Alfred Regnery. Fox News host Laura Ingraham credits Opus Dei–connected lawyer Pat Cipollone with her conversion.

Father John is gone — removed from his post by a sex-abuse scandal, he died last year — but the CIC is still on K Street. It is still run by Opus Dei (Latin for “the Work of God”), which is not focused on ministering to the masses (and if it were, it would be failing spectacularly, as more Americans are leaving the Catholic Church than joining it, by as much as four to one). Instead, it is focused on marshaling the people who have various forms of authority over the masses (Opus Dei reportedly calls them the “intellectuals”) to its various revanchist causes. The group targets, and attracts, people like Donald Trump’s current running mate, J.D. Vance, a convert to conservative Catholicism by way of Opus Dei–connected clergy and influencers.

Wait, Opus Dei, you say? That menacing group of self-flagellators to which albino assassin-monk Silas belonged that lies at the center of the web of conspiracies in The Da Vinci Code? In the Tom Hanks movie, Paul Bettany played Silas. The group was admittedly fictionalized to up the drama in the thriller, but it does, in fact, exist and has for nearly a century, one of the more exotic of the many factions within the vast Catholic Church. It would seem to be precisely the kind of mysterious clique with tentacles into the elites that would pique MAGA’s conspiratorial fever. But the CIC, which doubles as the Opus Dei office in Washington, and the national network of wealthy and powerful right-wing Catholics affiliated with it are among the most effective forces in MAGA world and the American Christian-nationalist movement. It is allied with Protestant Evangelicals in many of its goals but is more hierarchical and often more institutionally organized. Opus Dei can marshal centuries of intellectual heft of the Church behind it.

A great deal has been written this year about the resurgence of the Catholic right in America. This is not President Biden’s liberal Catholicism. In surveys, American Catholics as a whole are firmly in the mainstream in their political opinions, from contraception to divorce, gay marriage to abortion rights. But there is an elite vanguard on the rise that holds much more conservative views — many of these elites have some association with Opus Dei — and has sought to influence policies that might be enacted in a second Trump presidency. The now-infamous Project 2025 was cooked up under the auspices of the Heritage Foundation’s conservative Catholic and Opus Dei–connected president, Kevin Roberts. All three of the Trump-appointed Roe-wrecking Supreme Court justices (two of whom are Catholic) got there thanks in part to the tireless dark-money-funded efforts of the right-wing Catholic Leonard Leo, a major CIC donor who has also become the go-to conservative disburser of anonymously donated big bucks to political causes. The three other justices in the Dobbs majority are hard-right Catholics. Beyond the high court, current and former Washington power lawyers and influencers have Opus Dei connections. The current CIC board chairman, Brian Svoboda, is a partner with the big-shot law firm Perkins Coie. Former board members include Trump-administration attorney general Bill Barr, Trump White House counsel Pat Cipollone, and Kirkland & Ellis partner Thomas Yannucci. Opus Dei affiliates sit on the board of another giant in the right-wing political-donor network, the Bradley Foundation (which is currently pouring money into the rightist stream, including far-right Trumpist groups run by Stephen Miller and Charlie Kirk).

Details of the Opus Dei network in the American capital are a significant part of a new, deeply researched book by British financial journalist Gareth Gore, Opus: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy Inside the Catholic Church (Simon & Schuster; October 1). Gore traces the history of the cultish organization from Franco’s Spain through its expansion globally and, finally, to the group’s rising influence in Washington and the American conservative movement. (Opus Dei declined to comment for this piece, although it had expressed preemptive concern about the book when its publication was announced.)

Opus Dei runs colleges and elite private schools around the world as well as institutions like the CIC, all designed to attract and mold the influential. It has residences where its most dedicated members — “numeraries,” some of whom are ordained priests, as was Father John — live under strict regimens tailored to ward off the sensual temptations of the secular world even while encouraging participation in it. The residence in Manhattan houses numeraries in a 17-story building on 34th Street called Murray Hill Place, which has separate entrances for men and women.

Officially, Opus Dei has 3,000 members in the U.S., and Gore was told 800 of them are in Washington. Not all are numeraries living in the residences; there are “supernumeraries” who live among the rest of us. (There are also those called “cooperators” who are not officially members but are associated with the group and its various activities.) The names of numeraries and supernumeraries are not public unless the members want them to be. And Gore says the numbers don’t reveal the extent of the group’s influence: “When I first started writing the book, I became obsessed with establishing who is a member. I decided to give up on that. It is a rabbit hole down which you will be hunting forever.” What he found is that “under every stone, you find a whole ecosystem of Opus Dei affiliates.”

Opus Dei has seen its sway rise and fall in the Vatican over the decades, with the more traditionalist popes, including John Paul II and Benedict, more sympathetic. Recently, the more progressive Pope Francis has tried in various ways to rein in the forces of conservativism. But right now, in the U.S. anyway, the organization is on a roll.

Opus Dei was born in another period of conflict and turmoil not unlike ours: 1920s Spain, just before anarchists and socialists pitted themselves against authoritarian Falangists and monarchists, with the latter groups winning and forming what would become the longest running military-junta government in Europe, Francisco Franco’s regime. The founder of Opus Dei was a priest, Josemaría Escrivá, now Saint Josemaría, who envisioned a lay brotherhood of men who would engage in the Work of God, a brotherhood that ultimately thrived under Franco’s fascist regime.

From the beginning, the organization had cultish qualities. The founder’s instructions total hundreds of pages that dictate every aspect of life within Opus Dei. Life in the residences for the low-level numeraries could be harsh, in keeping with the founder’s ascetic, urge-denying ideal. Numeraries slept on wooden boards, and some, according to court records Gore references, worked for 12 hours a day for little or no pay. The corporal mortification that The DaVinci Code made much use of is, in fact, real. A former numerary told the Mail on Sunday in 2005 about the whip and the cilice (a spiked garter members strap on their thighs) at an Opus Dei house. “As a member of Opus Dei, I was expected to undertake a weekly discipline of private self-flagellation 40 strokes with a waxed, corded whip” former member John Roche wrote. “We were encouraged to ‘draw a little blood’ and frequently told how ‘the Father’ [Escrivá] … drew so much blood that he spattered the walls and ceiling with it.”

Escrivá’s rigorous spirituality was in service to a greater goal, bending adherents to the rules and morals of their creed: “The disease is extraordinary — and the medicine is just as extraordinary,” wrote Escrivá. “We are an intravenous injection, inserted into the circulatory torrent of society … to immunize the corruption of mankind and to illuminate all minds with the light of Christ.”

After spending six years on the book, Gore concluded that Opus Dei’s position of power in Washington today represents the fulfillment of the founder’s dream : “I’d summarize it as nothing less than the complete ‘re-Christianization’ of society — of everything from education to politics, the courts and the private life of each and every citizen,” Gore said in an interview.

The modern era of power and influence dates back to Father John and the CIC in Washington. The CIC was supposed to be just “a shopwindow for Opus Dei,” Gore writes. But within a decade, it became a hub for converting powerful D.C. players to a version of Catholicism shared by a tiny minority of American Catholics.

In the decades since Father John first came to Washington, numerary priests, affiliated converts, and their allies have worked in the courts and in league with non-Catholic “faith-based” politicians to crush reproductive rights, oppose gay marriage, and bash down the wall between church and state through Congress and at the Supreme Court. The conservative Catholic convert community in Washington includes some power players in this long game: One is Ginni Thomas, who converted in 2002, not long after Opus Dei associate Leonard Leo shepherded her husband, Clarence, through contentious nomination hearings and Anita Hill’s sexual-harassment allegations. Ginni Thomas has credited the Opus Dei–affiliated Scalias — Maureen Scalia, wife of the late Supreme Court justice Antonin “Nino” Scalia, has been spiritually directed at Opus Dei — for bringing Thomas back to the church. “Both Nino and Maureen [Scalia] really loved and prayed Clarence back to the Church,” Ginni Thomas has said. Clarence had grown up Catholic, and even considered becoming a priest, but had fallen away.

“There is a certain gift that Opus Dei has,” McCloskey said in a telephone interview with the New York Times during his heyday, “in terms of dealing with people of influence.” In only a few years, Slate called him “the Catholic Church’s K Street lobbyist.” The Catholic Herald called him the “unofficial chaplain to the upper echelons of the Republican Party” who ran his converting operation “like the brokerage business.”

Gore writes that this is exactly what Opus Dei leaders had hoped of Father John. Opus Dei leaders had identified McCloskey as a promising influencer when he was just a supernumerary in New York, then summoned him to Rome for training to become a numerary priest for just such a career.

Gore says that almost from its beginnings in Spain, Opus Dei aimed to target the most powerful people in society. The conversion process was systematic. “They identify ‘the intellectuals,’ as they call them,” Gore said. “They invite them to Mass, to talks for spiritual guidance sessions, and to Opus Dei retreats. They tell them that they are just trying to help ordinary Catholics to live out their faith. But, the whole time they are courting you, the numeraries and priests are collecting information.”

During his research, Gore learned the organization keeps detailed records on priests and numeraries to gauge how serious a potential convert or member’s Catholicism is, who is in their networks and families, and how much money they’ve got — information even gleaned sometimes, he said, from Confession, which officially is under seal of confidentiality.

“Opus Dei has more in common with the KGB or the Stasi than it does with other parts of the Catholic Church,” Gore said. “It has this meticulous recordkeeping. I spoke to one prominent D.C. conservative who said he had incontrovertible evidence that McCloskey had collected deeply personal and compromising information about him during Confession and then passed it on to senior members of Opus Dei.”

(One actual American spy is known to have been Opus Dei: FBI agent Robert Hanssen was a notorious double agent arrested in 2001. He died last year in prison, where he was serving a sentence for sharing national security secrets with the Soviets, including names of collaborators who were killed. Hanssen had confessed his role to an Opus Dei priest 20 years before he was arrested.)

McCloskey’s high-level converts testified to his charm and tenacity. “A few doses of Father McCloskey and we’ll turn this country around,” his convert Larry Kudlow, former Trump-administration director of the National Economic Council, said. Kudlow, who converted after recovering from a drug and alcohol addiction, had said of him, “Once Father John gets his claws into you, he never lets go.”

McCloskey was an effective converter but far from saintly in his personal life. Gore says McCloskey certainly strapped the spiked garter on and practiced the weekly self-whipping the group requires of its numerary priests — but corporal mortification did not quell the urges.

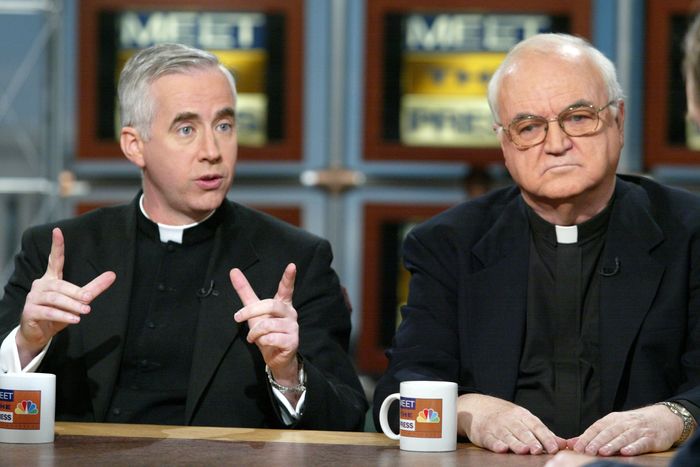

In November 2002 — the same month he appeared on NBC saying that priests accused of sexual misconduct ought to be protected — a woman he counseled lodged a complaint with Opus Dei that he had been touching her inappropriately during their sessions. For a year after the woman made her allegation, McCloskey continued to appear as a regular on national political talk shows, including Crossfire and Meet the Press, and on the Eternal Word Television Network, a conservative Catholic cable channel.

But in December 2003, McCloskey abruptly and without public notice disappeared from Washington. In 2005, Opus Dei quietly paid the woman almost a million dollars — a pile of money that came with a nondisclosure agreement. The payoff was not revealed until 14 years later, when the woman approached the Washington Post after reading a glowing article about McCloskey, who was by then ministering in Palo Alto. She told a reporter she had decided to tell her story, according to the paper, in order to help other women come forward (two more did).

Opus Dei spokesman Brian Finnerty — who broke down in tears talking about it — told the Post the settlement for McCloskey was the only sexual-misconduct settlement Opus Dei had ever paid out in the U.S. and that it was covered by “a special contribution specifically for it.” He declined to name the donor.

The telegenic Opus Dei priest is gone, but the converted politicians and influencers and their potent and well-financed allies have grown increasingly powerful in the decades since his work in the capital. And his style of anti-democratic warrior religiosity is now the norm in MAGA politics.

“Do I think it’s possible for someone who believes in the sanctity of marriage, the sanctity of life, the sanctity of family, over a period of time to choose to survive with people who thinks it’s OK to kill women and children or for — quote — homosexual couples to exist and be recognized? No, I don’t think that’s possible,” McCloskey said in a Boston Globe story published in the early aughts and recounted in Gore’s book. “I don’t know how it’s going to work itself out, but I know it’s not possible, and my hope and prayer is that it does not end in violence, But, unfortunately, in the past, these types of things have tended to end this way. If American Catholics feel that’s troubling, let them. I don’t feel it’s troubling at all.”

In an episode from the early aughts that Gore recounts in his books, McCloskey “actively encouraged [Kansas senator Sam] Brownback and other powerful politicians in his orbit to reconsider how they thought about democracy. ‘How many constituents do you have?’ McCloskey challenged a group of senators. Four million, nine million, twelve million came the answers from around the room. ‘May I suggest,’ the priest replied, ‘that you have only one constituent?’”

That moment, Gore writes, changed Brownback’s life. He was soon leaving the United Methodist flock and kneeling in the CIC chapel, receiving the sacraments of initiation under Father McCloskey’s hand.

In October 2022, three months after the Dobbs decision, the CIC hosted a $25,000-a-table dinner at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington to bestow its highest honor, the John Paul II New Evangelization Award, to right-wing fundraiser and Opus Dei benefactor Leonard Leo. Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas has called him “the No. 3 most powerful person in the world.” But his role in overturning 50 years of settled law affecting the private lives of hundreds of millions of Americans had perhaps catapulted him even higher in the eyes of the assembled ideologues.

Clad in a tux, his face shiny with perspiration so that he kept pushing his round glasses up his nose, Leo singled out the well-heeled guests as an oppressed minority and claimed his work in D.C. was a war with the Devil.

“Catholicism faces vile and amoral current-day barbarians, secularists, and bigots,” Leo said in a 20-minute speech still viewable on YouTube. “These barbarians can be known by their signs: They vandalized and burnt our churches after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, they show up at events like this one trying to frighten and muzzle us.” He assails “the current-day bigots, the progressive Ku Klux Klan … they repeat the KKK canard that Catholics want this country to be dominated and controlled by a theocracy.” The lawyer-lobbyist launched into a brief history of the Catholic Church versus its enemies, starting with the Christians repelling the Ottomans at Vienna in the 17th century, and concluded: “Catholic evangelization faces extraordinary threats and hurdles. Our culture is more hateful and intolerant of Catholicism than at any other point in our lives. It despises who we are, what we profess and how we act. Our opponents are not just uninformed or unchurched; they are often deeply wounded people whom the Devil can easily take advantage of.”

The CIC is among the many recipients of some of Leo’s donor money. His name is on a plaque of benefactors who paid for a recent renovation of the headquarters, but the organization’s gratitude is on display in other ways. The first image a visitor entering the building confronts in the foyer is not Christ on a cross but a large portrait of a smiling, modern-day teen girl with a bearded fair-haired man (presumably Jesus) holding his hand over her head and, behind him, a blurry nun. The girl in the painting is Margaret Mary Leo, Leonard Leo’s daughter. She died in 2007 at age 14 from complications of spina bifida. The portrait was painted by Igor Babailov, a prolific artist whose oeuvre consists mostly of powerful right-wing men — Justice Samuel Alito, George W. Bush, Rudy Giuliani, and anti-abortion fanatic and Domino’s Pizza CEO Thomas Monaghan are a few of his subjects. Also Putin, the pope, and Prince Andrew.

As it turns out, the Supreme Court released its Dobbs decision on June 24, which also was the date of the Feast of the Sacred Heart in the Catholic calendar that year. That feast is associated with Margaret Mary Alacoque (1647–1690), a saint who happens to share her name with Leo’s late daughter. Leo suggested to a pair of New York Times writers that it seemed possible the chief justice timed the ruling release to that date. When the CIC reopened after a renovation in September 2022 that Leo helped pay for, months after the Dobbs decision, the Babailov portrait of Margaret Mary Leo hung in the foyer. Some D.C. Catholics have claimed miracles in her name, a signal of a possible move to beatification. Sainting the offspring of a wealthy benefactor is a very 13th-century thing to do.

Leo has denied being an Opus Dei member. “To me, it’s clear Leonard Leo is a supporter of Opus Dei. Whether he is a member I don’t know, and in many ways I don’t care,” says Gore. “His actions speak for themselves.”

Leo put big money behind the work Father John started. His network and power have steadily grown with the three decades of right-wing advances, juiced by the 2010 Citizens United ruling and, in 2021, by a $1.6 billion windfall, after a secular Jewish Chicago billionaire, Barre Seid, signed over his electronics business — to a nonprofit trust set up by Leo. That sum enables Leo to spend $200 million annually without touching the nut, according to philanthropy experts. He is currently promising to dole out $1 billion with preference to conservative groups with plans to “weaponize” their ideas. It’s not impossible to imagine future historians regarding Leo as the Robert Moses of a theocratic America. Even without that extra billion, Leo’s network of donors is vast and includes secular billionaires as well as hard-right Catholic money. Neil and Ann Corkery (married longtime D.C. operatives and former Opus Dei members), Tim Busch (who has publicly and approvingly referred to the U.S. Supreme Court as “the Leo Court”), and anti-gay crusader Sean Fieler are a few of the Opus Dei–connected moneybags financing the conservative agenda. Leo-connected networks poured at least $50 million into the organizations behind Project 2025, according to Accountable.US. Project 2025 contains numerous proposals that align with Opus Dei concepts of how society should be ordered, from banning abortion to increasing the power of a conservative presidency, to making heteronormative marriage a national policy goal.

Leo has also done well enough personally that in 2018 he purchased a $3.3 million mansion in Maine near Acadia National Park. Using money from a fund he controls called the Sacred Spaces Foundation, he paid the Portland Roman Catholic diocese $2.7 million for the local church, Saint Ignatius of Loyola Catholic Church in Northeast Harbor, Maine. He made his wife choirmaster.

Leo’s connection to Opus Dei is also more personal — and more mysterious. Leonard Leo has said that his late daughter’s attachment to religion inspired him to become more religious, and since her death, he goes to daily Mass as often as possible. He has told stories, published in Catholic journals and a book, about how she underwent grueling surgeries, lived her life in a wheelchair, but developed a love for priests and nuns that was exemplary.

A Washington-area Opus Dei supernumerary named Austin Ruse, president of the fiercely anti-LGBTQ Center for Family and Human Rights, published a book about children whose short lives “point us to Christ” and included supposed miracles Leo’s disabled daughter had worked after death. In his book and subsequent articles in the Catholic media, Ruse described at least three miracles (the requisite number for beatification) attributed to Margaret Mary Leo.

When I reached out to Ruse to ask if there was a move underway to beatify Margaret, he immediately tweeted his denial, which he then deleted. But by collecting and reporting the possible miracles, he appears to have set the stage for the process to begin.

Gore believes Leonard Leo’s record of successful activism and Trump’s receptivity to the Opus Dei issues plus the Vatican’s slight move to the left under Francis have together attracted more right-wing Catholic money to the conservative cause and Opus Dei. With “recruitment beginning to trail off around the world because of an increasing incompatibility of its message to speak to the vast majority of Catholics,” Opus Dei presented itself as a champion for disgruntled American Catholic billionaires, which, Gore writes, “offered Opus Dei a new lease on life.”

Now Leo and his fellow crusaders have a chance to not only remake the Supreme Court in their image but also the White House itself. J.D. Vance’s path to conversion began with Opus Dei–connected priests and other converts, starting with Rod Dreher, a convert himself and “post-liberal” writer staunchly opposed to gay marriage. Dreher has since moved from the U.S. to live in Viktor Orbán’s Hungary, where he works for the Danube Institute, and has converted to Orthodox Christianity. Dreher has approvingly compared Vance to a young Orbán.

After Vance published Hillbilly Elegy, Dreher interviewed Vance for an article and apparently talked religion with him. He later connected Vance with Dominic Legge, a priest and former Justice Department trial attorney who has proclaimed, “A legal system … is ultimately subordinated to the highest common good, which is God himself.” This fall, Opus Dei will bestow on Legge’s organization, the Thomistic Institute, the same New Evangelization Award that it gave to Leonard Leo.

Vance has written that he was initially moved to consider Catholicism by reading Augustine’s City of God after listening to a Peter Thiel talk about the miseries of the self-centered yuppie meritocracy. Thiel is not Catholic — he was raised an Evangelical Protestant — but was influenced by the “mimetic desire” theory of French Catholic professor René Girard at Stanford.

Thiel was also close to the priest who ran the Opus Dei house on the Stanford campus. After his term at Stanford, Father Arne Panula was appointed vicar of Opus Dei, based in New York, from 1998 to 2002. He later became director of the CIC in D.C. until his death in 2017. Among his observations, delivered from hospice and published in a book: “What we call feminism is the attempt to flee both of the punishments handed to Eve: the pain of procreation and the pain of turning to men for approval and self-esteem.”

Opus Dei’s general posture toward women is that they exist to be wives and mothers. Josemaría Escrivá’s words in the last century remain as doctrine for the organization: “In the care she takes of her husband and children, a woman fulfills the most indispensable part of her mission.” Anti-feminist writers Kathryn Jean Lopez of the National Review and Mary Eberstadt have served on the CIC board.

Now awash in conservative donor money, the group is in the process of expanding its reach into new generations. It is opening 40 Opus Dei schools around the U.S., Gore said. “The endgame is the complete re-Christianization of society from the top down, by targeting the elites first. They have all kinds of initiatives aimed at young people,” Gore says. “They already have today’s elite. And now they’re going after tomorrow’s.”

The only downside of Leo’s success — for him and Opus Dei — is that all that winning has attracted unwanted notice. Journalists digging into his finances have made allegations of self-dealing and personal enrichment —including directing funds to Ginni Thomas — that Leo has denied.

These allegations attracted the attention of the Washington, D.C., attorney general. As of June, the AG was still looking into these financial trails, although Leo, through his attorney, has vowed not to cooperate. (In revenge for that prosecutorial intrusion, Representative Jim Jordan, a Republican of Ohio, opened a counterinvestigation into the D.C. AG.) Meanwhile, Leo recently promised to spend $1 billion of his dark-money war chest to “crush liberal dominance.”

This story has been updated to clarify that Rod Dreher has converted from Catholicism to Orthodox Christianity and that Dominic Legge will be accepting the New Evangelization Award on behalf of his organization.