Goodbye, Pamela Paul! You hardly knew us.

The controversial columnist is exiting the New York Times “Opinion” section this spring as part of a wave of job cuts. In 2022, after a decade of editing the Book Review, Paul joined “Opinion,” where she quickly gained a reputation as a liberal contrarian determined to court the rage of the online left. Over three short years, Paul has breezily claimed that free speech is under assault by woke activists, that gender medicine is mutilating a generation of children, and that America has become a dark, dystopian place where freethinkers get canceled and nobody reads books anymore. Through all of this, she has proudly donned the mantle of a beleaguered liberal, rejecting any suggestion that she has collaborated with the victorious right. “If people on the fringe are accusing me of ‘making straw-man arguments’ or ‘both-siderism,’” Paul said in 2023, “then I know that I’ve done something right.”

The outrage Paul’s work provokes can obscure its underlying frivolousness. Many of her columns are primers in aging gracelessly, full of half-hearted gripes about young people and a reflexive longing for the poorly remembered past. Her prose has the clean, placeless scent of laundry detergent; in another life, she would have been a minor satirist of bourgeois habit. (David Sedaris is one of her heroes.) But a career in attempted humorism has become untenable now that middle-class life as Paul understands it — reading literature, traveling the world, asking politely for things — has been ruined by the internet and inflamed by the woke left. And so Paul seems to have risen to the rank of professional opinion-haver by the sheer upthrust of discomfort, like an earthworm in the rain. Today she is a shouted murmur: Her principal opinion is that everyone else’s opinions should be as weakly held as her own — the idea being that if all our opinions were weaker, society as a whole might be stronger.

There is limited utility in devoting our attention to a person so rarely visited by serious belief. But Paul is a good example of an all-too-serious intellectual movement that has emerged from the wreckage of the Obama years, when “postracial” liberal optimism began to curdle into open contempt for liberatory struggles like Black Lives Matter or the fight for universal health care. I think of it as the far center: a loose coalition of disillusioned Democrats, principled humanists, staid centrists, anti-woke journalists, civil libertarians, wronged entertainers, skeptical academics, and toothless novelists, all brought together by their shared antipathy to what they regard as the illiberal left. The far center is for free speech and bourgeois institutions; it is against cancel culture, student protests, and radicalism of any kind. Yet it rejects the idea of a shared ideology or politics. Instead, its members see themselves as independently sane individuals — concerned citizens who wish only to defend civil society from the unbearable encroachments of politics. So the far center is liberal, in that its highest value is freedom; but it is also reactionary, in that its vision of freedom lacks any corresponding vision of justice.

It can be difficult to tell the far center from regular old conservatism. Nowhere is this clearer than in Paul’s views about transgender people. In her time at “Opinion,” she frequently promoted the idea that trans kids are actually a vulnerable population of mentally ill children being preyed upon by a sinister medical Establishment eager to castrate them. (One lengthy column was cited in a conservative legal brief just four days after being published.) In the wake of the election, Paul blamed Harris’s loss on the Democratic Party’s failure to embrace “nuanced and humane alternatives” to the unpopular agenda pushed by radical trans activists; at the same time she nobly acknowledged that trans people are “understandably fearful” of what is to come. This was rich: Paul is a zealot attired as a skeptic, one who has gladly paved the way for the anti-trans right — with the blessing of the Times itself. Make no mistake: The new Trump administration will eliminate every trans person in America if it can. The NCAA has already decided to bar trans women from women’s sports, and two major hospital systems in New York appear to have stopped treating trans kids. Meanwhile, Paul spent her first column after the inauguration complaining that people use the phrase “it’s all good” in situations where it is not, in fact, all good.

Like other reactionary liberals, Paul is stung by the insinuation that she has crossed the aisle, tartly reporting that she has “personally been slapped with every label from ‘conservative’ to ‘Republican’ and even, in one loopy rant, ‘fascist,’” when in fact her politics are “pure blue American.” This is an old irritation for Paul, who seems to have grappled for decades with the specter of her own conservatism. In her first book, about early divorces, she laments that Republicans have cornered the market on family values. “The majority of Americans believe in marriage and family, but only conservatives seem to actively defend them,” writes a frustrated Paul, fresh off her own divorce. “It’s become impossible to advocate marriage without implying a reactionary social agenda.” The sentence is quite illuminating: The far center often feels it has the right to advocate a cause with the political label steamed off. In truth, Paul has devoted many books and much of her editorial work to the idea that child-centered heterosexual marriage is the fundamental social institution. Clearly, she does not object to traditionalism; what she does object to, quite strenuously, is the thought of herself as the kind of person who would believe in it.

So in the most basic sense, the reactionary liberal is reacting against her own feelings of political conviction, as if politics were a virus she had contracted from someone at a party. The political theorist Corey Robin has written that all reactionary movements begin with a disturbance in “the private life of power” — the southern slaveholder, for instance, defended slavery because daily life as “the master” had led him to perceive emancipation as an “intolerable assault upon his person.” In this way, the reactionary is driven by a desire to recover a greatly cherished self-image; what distinguishes one type from another is the content of that image. Traditional conservatism, Robin writes, is an “elitist movement of the masses” that aims to democratize the feeling of dictatorship: The working-class Trump supporter is meant to see his own supremacy rapturously reflected in his leader’s innate grasp of power. Of reactionary liberalism, we might say the opposite: It is a populist movement of the elites, an explicit bid by the intelligentsia to defend its bourgeois way of life on the grounds that its exceptional moral sensibility gives it unique access to the human experience. The conservative says, “You too can be superior.” The reactionary liberal says, “I alone am average.”

Since her earliest work, Paul has embodied this tension. On the one hand, she has long claimed to speak for a “vast middle ground” of Americans, people who support simple, commonsense approaches to wrongly “politicized” issues like parenting, education, and gender. “Marriage is a centrist, humanist position — if it can be called a ‘position’ at all,” she writes in the divorce book. (An early stint at American Demographics, a consumer-trends magazine, seems to have taught her a reverence for “middle America.”) On the other hand, Paul regularly presents herself as a freethinking loner who would sooner walk out of a corporate interview and buy a one-way ticket to Thailand, as Paul apparently did upon graduating college, than surrender to the ideology of the masses. “When it comes to gathering in large groups and yelling, you can count me out,” she has written of her distaste for political protests. “I’ve never been much of a tribalist or a joiner, and I have no use for conformity of thought.”

The incoherence of this idea — that the middle of the road is located off the beaten path — should be obvious. It is also intentional. One reason the far center has not yet been properly theorized is that its pseudo-Socratic ethos of “questioning everything” is meant to bring about an admirable state of intellectual collapse. The left, Paul tells us, flatters itself with how much it thinks it knows; Paul herself has the good sense to flatter herself with how much she doesn’t. Early in her career at the Times, she began writing a column that purported to give readers “the gist” of the latest social-science research with a strong preference for counterintuitive findings. (“Contrary to popular belief, relationship woes bother men more than they bother women”!) In most cases, Paul’s source was a single new study or unreviewed conference paper — hardly grounds for scientific certainty, as she herself loves to argue in the case of gender-affirming care. But the column was less about arriving at the truth and more about a bland faith in the inherent value of debunking conventional wisdom. This is the sort of thinking that can lead a writer into the perilous misconception that she is butchering sacred cows when in fact she is cultivating credulity.

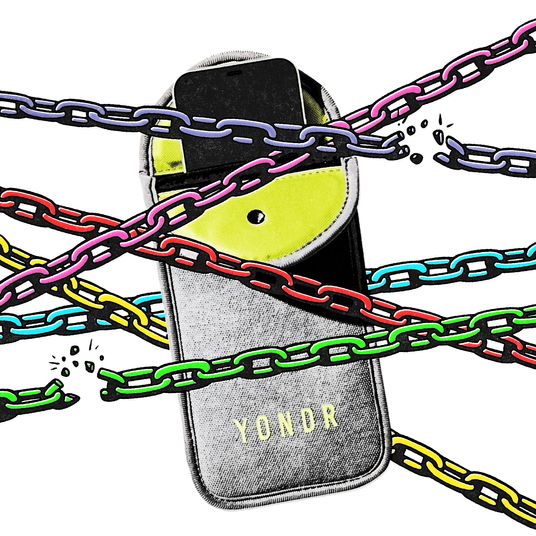

For in the end, the reactionary liberal is a ruthless defender of all that exists. Paul’s 2021 book, 100 Things We Lost to the Internet, is a cabinet of banalities wherein the usual liberal virtues (civility, patience) sit glassily alongside a predictable middle-class nostalgia for things like scouring the Bloomingdale’s shoe department for the right dress pump or taking in a Broadway show without hearing the low buzz of a text message. “There was nothing to do but let go of whatever might be happening outside the theater and lose yourself in what was happening onstage,” Paul writes wistfully. “You simply couldn’t be reached.” It is a great dream of the reactionary liberal not to be reached. Paul will freely admit, for instance, that it is immoral for Israel to kill tens of thousands of civilians. Yet it is no less immoral for student protesters to erect an ugly encampment in the middle of the quad and hurl slogans at the police. This is because political action is an unacceptable snag in the continuity of bourgeois experience. One gets the sense that politics has gone off, like a cell phone, in the darkened theater of Pamela Paul’s mind. It is worse than wrong: It is rude.

Some members of the far center will protest that, far from being uninterested in politics, they are simply defending basic principles of liberalism that have come under assault in our polarized times. To this, we may reply with one of their own maxims: Two things can be true at once. In practice, the liberal political tradition has always harbored a certain wariness of actual politics. Adam Gopnik, one of its recent champions, has written that liberalism is founded on “a feeling for normal human frailty and for mercy before justice and humanity before dogma.” This humanist assumption that people tend to be “wrong about everything” means that the liberal always favors a program of incremental reform. The idea is that the world can always get better, but only a little better, ideally through “invisible social adjustments” that sidestep the risks of direct political action. “Liberal reform, like evolutionary change, is open to the evidence of experience,” writes Gopnik — a perfectly inoffensive notion, until one remembers that evolution is based on letting the unlucky die.

For the reactionary liberal, political conflict is never something to be resolved through struggle; it is something to be transcended through tolerance. Paul tells us that, as a young woman, she was once a voracious but undiscerning reader of books who allowed their contents to “gather agreeably in my head” before dispersing. Then she briefly married Bret Stephens, her future conservative colleague at the “Opinion” section, finding in him a welcome spur and willing sparring partner who taught her a healthy skepticism of all views, including her own. What this anecdote really illustrates is that the reactionary “values friendship more than agreement,” as Robin observes. A certain intellectual flexibility is often the price of admission to the most desirable social circles, especially as the young liberal professional moves up the economic ladder and encounters more bona fide conservatives among the de facto ones. (Paul reports that her parents named her after the heroine of the 1740 novel Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, a much-parodied morality tale about how to “be respected by everyone.”)

In her veneration for books, Paul represents a strong trend within the far center. The philosopher Michael Walzer has recently written that liberalism’s moral sensibility “is almost certainly better represented in literature than in politics.” Working at her local bookstore as a teenager, Paul was drawn to books by “troublemakers” and became “nearly delirious in my desire” to sell The Satanic Verses, feeling that the fatwa against Rushdie had upgraded her clerical duties into “a campaign to save literature from the forces of darkness.” In recent years, Paul has decried the “growing forces of censorship” within the publishing industry, where book deals are scuttled for political reasons and authors forbidden to cross identity lines. Naturally, she has abandoned this defense of free expression whenever it has suited her: In her second book, Paul argues that pornography is a harmful commercial product that can and should be regulated, like cigarettes or Nazi artwork.

Now it is obvious that novels are also commercial products with real-world effects; anyone who complains about the decline of American reading habits already believes this. But for Paul, literature is a kind of glass container for the world, one that permits the safe pleasures of empathy without the distress of responsibility. In her column on protests, Paul tells us that she “would rather read about strikers in Germinal than march on a picket line.” And why not? It only costs a few francs. The bourgeois dream of a life without consequences is exactly the sort of late-imperial decadence Zola was critiquing, but even this critique is welcome so long as it remains swaddled in the pages of a novel.

So it was for a young Paul, who as a girl realized that books were a way for rule-followers like herself to experience “a kind of secondhand rebellion.” Ever since she was the children’s editor at the Times, Paul has advocated for childhood reading as an early education in liberal values, arguing that the best children’s authors write about oddball characters, absurd situations, and the anarchic exercise of freedom. For evidence, she points to Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, in which the young Max “chases his dog with a fork and yells at his mother — only to be crowned king and served a hot dinner.” But this is a poor reading. What actually happens is that, tiring of the wild things, a lonely Max willingly sails back to his bedroom to find a hot dinner lovingly set out by his mother, who (we suddenly realize) knew all along that he would return. In other words, the book is about the successful brokering of obedience: Max’s brush with wildness teaches him that childish freedom and parental authority are two sides of the same coin. The story thus acts as an allegory for itself; after all, the most immediate purpose of any picture book is to persuade the little reader that going to bed is her idea.

We must remember that the family is one of the few openly authoritarian institutions in a liberal democracy. The liberal tradition since at least Locke has understood parenting as a natural form of authority that, while it is no model for government, is a necessary response to the state of temporary insanity known as childhood. Paul would never claim that political life should resemble family life; what she does seem to say is that if society were more like a family, then politics could be largely replaced by sensible parenting. The task is simply to enlarge the family sphere until it covers the whole republic. This is why Paul’s campaign against trans people has focused on “vulnerable” children—or really, their vulnerable parents, whom a horde of quacks and activists have stripped of their natural freedom to dominate the human beings in their care. This is the critical edge: where the reactionary liberal’s single-minded pursuit of freedom leads her into the breathless endorsement of authoritarian violence. When Columbia’s president called in a notoriously violent counterterrorism unit of the NYPD to raid the student encampments, Paul praised her for acting like a “real grown-up” in a sea of spoiled brats. “Let’s hope this teaches the students a lesson,” she wrote. “They clearly still have a lot to learn.”

That is the entirety of Pamela Paul’s political vision: It’s bedtime again in America. One gets the sense that we have woken her up in the middle of the night, racing around the kitchen banging on pots and sobbing incoherently. It falls to her, the adult in the room, to wrestle us kicking and screaming back under the covers. “Refuse to react,” she advises in her most recent column, telling readers that the best response to the authoritarian shock and awe of the past few weeks is to engage in cheeky acts of private rebellion. “Personally, I avoid using favorite Trump words like ‘beautiful’ and ‘huge,’” she writes, “which nobody else notices but which brings quiet satisfaction.” This is a very nice thing for the book lady to say to people who have been forcibly loaded onto planes or refused urgent care by their own doctors. But it is not alarmist to notice fascism; it is quietist to hate alarms.

The wild things are already here: the barrage of unlawful executive orders, the stunningly cruel plans for mass deportation, the junking of the federal government by a lunatic. But as the right tightens its grip, the far center will at least be forced to show its stripes. Some will drink and be merry or go hiking through the Thailand of their own minds; others will roll over and beg. As for Pamela Paul, I imagine she will just disappear into the nearest book. She has written that everyone has a “right to be forgotten.” For once, I think we agree.