On his first day in office, President Donald Trump issued a flurry of executive orders intended to curb both legal and illegal immigration. In one of his most controversial orders, Trump called for the revision of the constitutionally recognized right of birthright citizenship to exclude the children of people in the U.S. unlawfully or on a legal temporary basis. The order, which is viewed by many as legally dubious, was immediately targeted by numerous lawsuits, starting off a protracted fight that will likely end at the Supreme Court. Within days, a federal judge temporarily blocked the order, calling it “blatantly unconstitutional.” I spoke with Gerard Magliocca, a professor at Indiana University’s Robert H. McKinney School of Law, about the president’s chances in court and whether a push for a constitutional amendment could be next on the horizon.

Trump’s executive order looks to redefine the constitutional right of birthright citizenship to exclude the children of noncitizens. In your opinion, does he have any legal ground to stand on?

No. Now, there’s really two reasons for that. The first is that this is an executive order, not an act of Congress, right? And so the first question is, does the president on his own have the power to redefine citizenship? And to do that, he would have to be able to point to some law enacted by Congress or something in the Constitution specifically that says the president can do this — and there is nothing like that. The Supreme Court has held, in some cases during the Biden administration when President Biden tried to do certain things on his own through executive orders like student-debt relief or certain kinds of COVID policies, that there was no statute that gave him the power to do these things.

Now, the second problem is even if you thought there was some law that supported the executive order in an act of Congress, it’s unconstitutional. The reason it’s unconstitutional is that when the 14th Amendment was ratified, there were only a couple of very narrow exceptions to the rule that everyone born here is a citizen and none of those exceptions have anything to do with the fact that your parents may or may not have done something. The example that the executive order cites is to say people who have come here illegally are invaders. And it is true that back when the 14th Amendment was ratified, if you had an invading army — Canada invades Maine and then children are born in Maine under Canadian occupation — those children would not be considered birth citizens because, in effect, that part of the country would not be under the control of the government, right? It would be totally under enemy control.

That’s a pretty big difference from a situation where you have people coming here peacefully, not from enemy countries, who are perfectly well under the authority of our government because they’re being deported or they could be deported. So, the only example that’s being cited as a basis for the constitutionality of this is far removed. And, by the way, there’s not a single example of that exception for the foreign invaders ever being invoked. It’s never happened. It’s an exceptionally weak case for both reasons.

The Trump administration’s legal argument seems to hinge on the idea that children who are born in America to parents who are here unlawfully or on temporary status are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States. What do you make of that argument?

Okay, if that were literally true, then they couldn’t be deported, right? In other words, the ordinary way in which everybody understands “subject to the jurisdiction” is you’re subject to the law and legal authority. And everybody agrees if you’re here illegally, you’re subject to the law. You can be deported. So, what are they trying to say? They’re trying to say, “Well, it doesn’t really mean that.” It means something else, which somehow means something about whether your parents are here legally or not. So, that’s the part where it kind of falls down.

Now, the exceptions that existed back when the 14th Amendment was ratified all are consistent with not being subject to the law. If the invading army, you know, the Canadians hold Maine, well, the people of Maine are not subject to American law because the American government’s not in control at all, right? They’ve been totally kicked out. There was this exception for, well, what if you were the child of a foreign ambassador? The ambassador from Spain has a baby here. Then people said, well, all right, diplomats have diplomatic immunity. No, they’re not subject to American law in the way that everybody else is. So, that doesn’t count. But again, that has nothing to do with the fact that someone is here illegally because we have the authority to remove them.

And I doubt that the Trump administration would argue they don’t have the right to deport those people.

That’s right. On one hand, they’re saying, “We can deport them and we’re going to do that.” And then on the other hand, “Well, we don’t have any control over them and that’s why they’re not entitled to birthright citizenship.” It just doesn’t hang together. The strongest argument that you can make for this position is simply that when the 14th Amendment was ratified, the United States didn’t really have any immigration laws. There really wasn’t any such thing as people who were here illegally. So, if you were to go back and try to find, well, did anybody say anything about this issue then, the answer is no because why would anybody have thought about it or said anything about it? It just wasn’t on their radar screen. Okay, so someone can say, “Look, this is an issue that wasn’t there then and so you can’t find anybody specifically who says, yes, the children of people who are here illegally are citizens if they’re born here.” But, of course, you can also find no evidence for the other side of that either, that somehow those children are excluded. So, it really says nothing about it at all, right? Then what you’re left with is there were these couple of exceptions that they had, and those exceptions were all things that had to do with, are you subject to the law or not? And since people who are here illegally are subject to the law and subject to deportation, those exceptions don’t cover this situation. And of course, you could say the consistent practice for the last 100-plus years has been to say that those children are citizens.

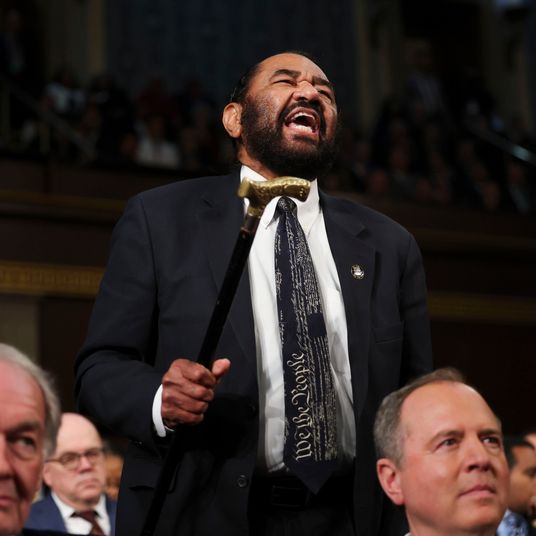

Trump has indicated that the Justice Department plans to appeal the judge’s ruling and continue to defend the order in the courts. With the order already facing numerous challenges and that number likely to grow, what can we expect this legal fight to look like?

Well, the Supreme Court is certainly going to take this case when it gets to them because it’s this very important case. It’s hard to say how long that will take. But that’s where it’s going to end up. All the other court rulings are, to some degree, preliminaries for that and are really just a way of fleshing out the various arguments and going through all the historical materials and all of that sort of thing. But it’s definitely going to end up in the Supreme Court, probably next year sometime.

Normally I don’t make predictions. That’s a hazardous business. But I will say the Court will certainly reject as illegal this order. Now, they might only say, “Look, it’s illegal because the president can’t do this sort of thing on his own,” and they might not talk about the constitutional question at all. But you’ll get at least seven votes for a Supreme Court opinion striking this down.

Even with the conservative majority on the Court right now?

Yes, because you have this twofold problem, right? The problem of the president acting unilaterally and the problem of unconstitutionality. Suppose it was definitely constitutional for Congress to do it, but the problem is that the president is doing it. Or the president can definitely do it if it’s constitutional or something like that. Then that makes it a little harder to say what would happen. But when you have two very substantial objections, easily more than five are going to agree on one or more of them.

While this plays out in the courts, is it likely that the order will remain frozen in the interim or will that depend on each next step? Is that at the judge’s discretion?

I think odds are that it will remain frozen. I mean, you can also say even if it isn’t, the order applies only to babies born after January 20. And so as a practical matter, not a whole lot is happening with babies and toddlers in the span of a year such that their citizenship status really means anything. So, even if the order were to come into effect in between certain court rulings, I don’t know that it really does anything much for the brief period of time that you’re talking about. But odds are it’ll probably be on hold all the way through or for most of the time through the litigation.

If Trump’s efforts fail in the courts, his last option could be advocating for a constitutional amendment to address the issue. Though Republicans currently control Congress and had significant wins across the country including in statehouses, how difficult of a process would that be for his administration?

It would be very difficult because I just don’t think you could get the necessary majorities in Congress. To get a two-thirds vote, you’d have to get about, what, 14 Democratic senators to go along. That seems like a pretty tall order. Now, it is worth pointing out, though, if the Court were to say, “Look, you can’t do this with an executive order. We don’t express any view on whether an act of Congress can do this,” then the administration could go to Congress and say, “Look, we want you to pass a law that says no birthright citizenship for these people.” Now, of course, that’s easier. I don’t know that they could get such a law passed. That’s also challenging given the very tight numbers in the House of Representatives, right? But it’s at least more possible for that to happen than an amendment.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More on politics

- Melania Trump’s Mysterious Amazon Documentary: What We Know

- Polls Show Trump Speech to Congress Didn’t Change Anything

- Elon Musk ‘Elated’ to Learn Congress Might Rubber-Stamp His Cuts