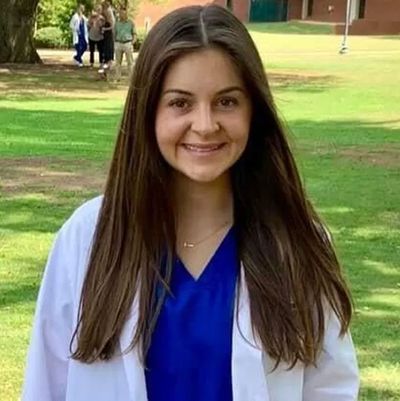

Last Thursday morning, a nursing student named Laken Riley, a junior at the University of Georgia, went out for her morning jog in Athens. Riley was an avid runner, well known in the local running community, and had recently competed in the annual AthHalf, one of Athens’s most beloved institutions. She took her regular route around Lake Herrick, an on-campus trail adjacent to Oconee Forest Park, near the campus’s Intramural Fields. When she failed to return home, her roommate, a fellow runner and Riley’s best friend, called the police. Within the next hour, they found Riley’s lifeless body in a wooded area just off the trail. Her skull had been crushed.

I know exactly where Riley was killed, because I also live in Athens, and I’m also a runner, and I also have run the Lake Herrick trail; it’s a half-mile from my house. Athens is a beautiful city to run in — hilly, sure, but open, comfortable, and scenic. Some people prefer the flat sidewalks of Milledge Avenue, past the sorority and fraternity houses; some like winding through campus, ending at Sanford Stadium, home of the recent two-time college-football champion Georgia Bulldogs. My personal favorite route is the Firefly Trail, whose highlight is a newly constructed bridge replacing the famous railroad trestle featured on the back cover of R.E.M.’s classic album Murmur. But the Lake Herrick trail may be the most bucolic of them all, the one place in town where you’re totally surrounded by nature and outside the bustle of campus life. It’s a place where, until recently, you could feel peaceful and safe.

People run for a variety of reasons, but a primary one is that it’s an opportunity to be alone with your thoughts. I started running 12 years ago, when I lived in New York City, because I was a smoker when my wife became pregnant, and needed to find an activity that would help me stop. My wife was a dedicated runner, and I saw how running instilled a certain calmness to her, clearing her mind and preparing her to be able to face the day ahead. When we moved to Athens in 2013, we found our running true north. She’s an early-morning practitioner, usually back before I’m even awake. And I can still see that calmness, that peace, upon her return.

But she has had to fight to reach that calmness, that peace. She has told me how often she feels watched on her runs. How she has been followed. How she has been spit at. How she was even once swung at. I have never had any of those fears, not once. Because I am a man.

Riley’s murder, the first homicide on campus in more than 30 years, sent a wave of terror through Athens, but it hit the running community particularly hard. Fear was palpable among women runners in the first 24 hours after her death, and their stories made it clear that what I — along with many of my fellow male runners — had thoughtlessly considered a safe, solitary activity has always been far more fraught for half the population. Women spoke of the precautions they constantly have to take, from going out with running buddies to avoiding isolated areas to carrying alert systems, weapons, or even Tasers with them anytime they leave the house. (My primary concern when I set out is whether I remembered my headphones.) Riley’s assault and murder — one of several involving women runners in recent years — was a reminder that every time women go for a run, they have to be conscious of the possibility of male violence. Or, more accurately: They have to be as conscious of the possibility of male violence as they always are. My wife reminded me of the Margaret Atwood quote: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.”

For a day, that’s what the conversation around Athens was about: the constant threat of male violence, and how difficult it is for men to understand what women have to go through. Then police announced that they had arrested a suspect, a 26-year-old man named Jose Antonio Ibarra. And then they added a detail that changed everything: He was an undocumented immigrant from Venezuela. People immediately stopped talking about male violence.

On Monday afternoon, Georgia governor Brian Kemp, who grew up in Athens, attended the University of Georgia, and has two daughters in school there, came to campus to speak to the local Chamber of Commerce.

“[This] was preventable,” Kemp said, “because we just have a nightmare in this country with mass migration and then have people that are here illegally breaking our laws and they’re not telling anybody and reporting this to us.” Earlier, Kemp had publicly posted a letter on Twitter that he sent to President Joe Biden, demanding answers on Ibarra’s immigration status and claiming Biden’s “continued silence” was “outrageous.”

What had been a local tragedy immediately became more grist for America’s forever culture war. Representative Mike Collins said, “The blood of Laken Riley is on the hands of Joe Biden, Alejandro Mayorkas, and the government of Athens-Clarke County.” Donald Trump posted that the murder was proof that “Biden’s Border INVASION is destroying our country and killing our citizens!” Republican Houston Gaines, Athens’s state representative who lives just down the street from me, is actively attempting to replace the Democratic (and Latina) county district attorney general Deborah Gonzalez from the prosecution. “She’s not ready to handle this case,” Gaines said Monday. (Gonzalez has already brought in a special prosecutor.) The Republican-majority state legislature, still stinging from the state going blue in 2020 and two key Senate losses shortly thereafter, is using Riley’s murder to stir up the GOP base. Never mind that two weeks ago, national Republicans refused to pass a bill that would have cracked down on immigration, solely because Trump thought it could hurt Biden in the election. The cynicism of the whole enterprise is overwhelming, as is its insistence in ignoring the actual issue at hand.

Republican rhetoric around the killing also illustrates how far the bar has fallen for acceptable racial discourse over the last decade. When Trump came down from that escalator in 2015 to announce his presidential campaign, his White House aspirations were not the immediate takeaway from his press conference. It was the fact that he had called Mexicans “rapists.” It led NBC to immediately drop him from The Apprentice and sever their business relationship, proclaiming that “respect and dignity for all people are cornerstones of our values.” But now, Trump’s notion — that immigrants are more likely to commit crimes and be violent toward “normal Americans,” something that’s empirically, plainly not true and is, of course, a textbook definition of racism — is now not only not taboo and worthy of universal disgust, it is mainstream Republican dogma, even from politicians like Kemp, who had earned a reputation, more because of his resistance to Trump’s claims of voter fraud than any sort of policy stance, as a moderate within the party.

As Ibarra sits in the Clarke County Jail, down the road from where my older son plays Little League baseball, the story has gone national, and it has stopped being about Laken Riley or the women like her. We’ve already moved on from the actual death of this college student, this runner, this active sorority member and devout Christian, this babysitter of two of my friends’ children. We’re not talking about her, or women like her. We’re all just yelling at each other again. Laken Riley isn’t dead because she ran into an undocumented immigrant; she’s dead because she ran into a violent man. That’s the conversation this community was having in the aftermath of her death, and what the vigils in this town are attempting to mourn. But it is being obscured, even commandeered, by election-year politics.

The other night, my younger son played in a soccer game against another elementary school here in Athens, one with a high percentage of Latino students. The game, happening so soon after the tragedy, would have already been played under a fog of grief. But now there was fear. There was fear in the eyes of the Latino parents. There was fear in the eyes of every woman in attendance. There was fear everywhere. An awful tragedy has expanded, somehow, into a feast for sadistic opportunists, intended specifically to divide a community that has been desperately trying to find some way to come together. We looked to the field, and among each other, to try to find some way to unite. But then the game ended, and we went back home, to our silos, to our phones, scared and alone, again.