There was a simple question at the heart of Monday morning’s opening arguments in Donald Trump’s criminal trial in Manhattan: What’s the big deal? You may think it would be unnecessary to establish the stakes of the first prosecution of an ex-president, taking place amid a campaign that could very well return him to office. If Trump were going on trial for any of the other crimes, in other jurisdictions, that he is accused of committing — violating the Espionage Act, using political pressure to try to overturn the election in Georgia, subverting the peaceful transfer of power on January 6 — the answer would be self-evident. Yet this morning in Manhattan, Trump went on trial for the least of his offenses, making payoffs to a porn star.

Criminal law is not about narrative proportion, though — it deals in binary choices. Trump is accused of breaking the law, and though this trial may not be about the worst thing he ever did, he will still face a jury of 12 New Yorkers inside the scaffolding-shrouded criminal courthouse on Centre Street. It’s a fitting place to judge a squalid crime. The 15th floor, where the trial is being held, is locked down every morning, but elsewhere inside, the routine of arraignments, plea hearings, and sentencings keeps grinding forward. The grungy bathrooms smell like smoke, and sometimes you can find balled-up jail jumpsuits on the floor, left behind by perps who just got released.

Judge Juan Merchan’s courtroom is unadorned. There is a little American flag — the type schoolkids wave for a presidential motorcade — tacked to a bulletin board on the wall, a few feet from a paper sign that reads “Active Shooter” with safety instructions beneath. The defendant in the case of People v. Donald Trump came in with a large retinue of aides and attorneys and took his seat at the defense table. As always, a group of five pool photographers rushed in and photographed him for a few moments as he sat there seething like a caged animal. Then he sat back, wearing a blue tie and a blank look on his face, as Matthew Colangelo, representing the Manhattan district attorney’s office, rose to begin the case for prosecution.

“This case is about a criminal conspiracy and a cover-up,” Colangelo said in his opening words to the jury, “a criminal scheme to corrupt the 2016 election.”

It is easy to understand why Colangelo — a former Justice Department official who came to New York to handle the trial — wanted to start with some reframing. The “hush money” case, as it is often called, is one that even some prosecutors were reluctant to bring. It was originally a component of a wide probe into Trump’s finances that had been initiated under former New York district attorney Cyrus Vance, who charged the longtime chief financial officer of the Trump Organization, Allen Weisselberg, with evading taxes on his compensation in an effort to flip Weisselberg against his boss. But he refused to turn on Trump. After a new district attorney, Alvin Bragg, was elected in 2021, he decided not to pursue the financial-fraud case. (Attorney General Tish James pursued it as a civil lawsuit, which resulted in a $455 million judgment against Trump.) All that was left after the investigation fizzled was a subset of charges related to payments to Stormy Daniels.

Under Vance, the DA’s office had been hesitant to pursue the Daniels case on its own for reasons both philosophical and tactical. If you were going to try Trump, it seemed to some of the key prosecutors involved, it should be for a major crime. And the Daniels affair seemed more seedy than felonious. The underlying facts concern a $130,000 deal that Michael Cohen, Trump’s then–personal attorney, made to buy silence from the actress when she was trying to sell a story about a sexual liaison with Trump to a tabloid. (Trump denies the affair happened.) The following year, after Trump became president, he allegedly arranged for his company to pay Cohen $420,000 to cover the payoff, expenses, taxes, and a bonus, all disguised as a “retainer agreement” for his legal services. Cohen pleaded guilty to federal crimes related to the payments in 2018, after which he became a cooperating witness for the DA’s office. Still, he was hardly an ideal witness: a convicted felon whose agenda was evident from the title of his memoir, Disloyal, and its sequel, Revenge.

Under New York State law, the crime Trump has been charged with, falsifying business records, is a misdemeanor unless it is committed in the course of another felony. It is not illegal to pay off a mistress or to reimburse a lawyer. Thus, in his opening statement, Colangelo had to explain how the $420,000 paid to Cohen had been part of a larger criminal scheme. In the prosecutor’s telling, it was all part of a plot initiated in 2015 in a meeting at Trump Tower between Cohen, his boss, and David Pecker, who was then the chief executive of the company that owned the National Enquirer. “Those three men formed a conspiracy at that meeting,” Colangelo said.

The “Trump Tower conspiracy,” as the prosecutor called it, allegedly had three elements: The Enquirer would publish positive stories about Trump and negative stories about his opponents, and most important, according to the prosecution, Pecker agreed to act as Trump’s “eyes and ears” down in the gutter. On at least three occasions, including with Daniels, Pecker or his subordinates alerted Trump to salacious stories about him that were being shopped, and they helped him get the stories snuffed out by persuading the sources to agree to sell the rights to their stories to the Enquirer or to entities controlled by Cohen in an industry practice known as “catch and kill.”

“You will hear the defendant in his own voice,” Colangelo promised, indicating that the prosecutors plan to play tapes of Trump’s involvement in the catch-and-kill negotiations. “You will even hear Mr. Trump suggest in his own voice, you will hear him suggest paying in cash.”

None of this will surprise anyone who has followed Trump’s symbiotic relationship with the tabloid press — for which he has long been both a character and a source — or who has any familiarity with the transactional nature of that business. But according to the prosecution’s theory, the rules changed for Trump in 2015 whether he realized it or not. What might have been merely a sleazy deal when he was a celebrity became a felony because he was running for president. “Look, no politician wants bad press, but the evidence at trial will show that this was not spin or communications strategy,” Colangelo said. “It was election fraud, pure and simple.” The prosecutor said that as Trump began racking up states on Election Night in November 2016, the ramifications set in for one of the lawyers who represented Daniels in the hush-money deal.

“What have we done?” the attorney texted a top editor at the National Enquirer.

If you believe Trump should be held accountable for everything he did after that — a familiar litany of high crimes and misdemeanors, for which he was twice impeached — it may be easy to shrug off any concerns about proportionality or technical imperfections in the hush-money case. Al Capone, as anyone who has seen The Untouchables knows, was put away for tax evasion, not the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. In the weeks before this Trump trial began, some legal experts who had previously minimized its importance came around to the opinion that, in its grubby simplicity, the hush-money case had its merits. “Now, everybody’s coming to the table and saying, ‘We need to take another look at this case because we all dismissed it,’” says Karen Friedman Agnifilo, a former top lieutenant to Vance in the DA’s office. “Dismiss it at your peril.” Even some of Trump’s loudest defenders have trouble seeing a route to an acquittal. “In New York,” says the famed attorney and former Trump lawyer Alan Dershowitz, paraphrasing the legal adage, “if you indict a ham sandwich named Trump, you’ll get a conviction.”

“President Trump is innocent,” his lead attorney, Todd Blanche, said as he began his own opening statement. “He is cloaked in innocence. And that cloak of innocence does not leave President Trump today. It doesn’t leave him at any day during this trial. And it won’t leave him when you all deliberate.”

Blanche previewed the elements of his defense. On one level, it is not much different than the case made by most every other defense attorney representing most every other defendant who passes through the Manhattan criminal-courts building. The prosecution has the burden of proof; the star witness is a fink. “He is a convicted perjurer. He is an admitted liar,” Blanche said of Cohen. Just the night before the trial, the attorney claimed, Cohen had talked about wanting “to see President Trump in an orange jumpsuit.” He claimed Daniels had lied about the sexual encounter and had threatened to go public with it in “an attempt to extort President Trump.”

“Objection,” one of the prosecutors said.

“Sustained,” said Judge Merchan.

Still, the jury heard the word extort, and maybe Blanche succeeded in planting a seed of doubt. His objective over the rest of the trial, which is scheduled to last six to eight weeks, will be to grow it, little by little, asking the jurors, Was this really as big a deal as the prosecutors suggested? Was it really election fraud? Did it really change history? Or was this trial just about some money and a nondisclosure agreement signed between two consenting adults, one of whom was running for president and wanted to avoid an embarrassing scandal?

“I have a spoiler alert: There’s nothing wrong with trying to influence an election,” Blanche said. “It’s called democracy.”

More From This Series

- Why Michael Cohen Still Misses Donald Trump

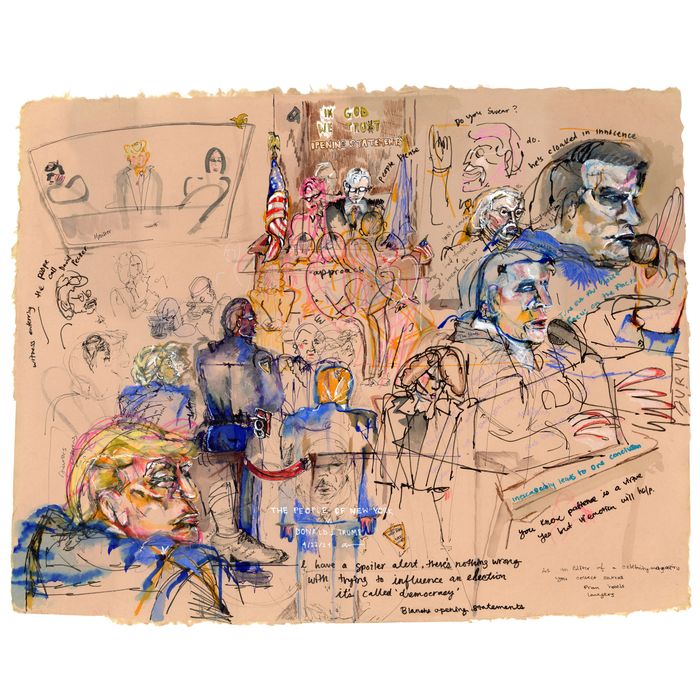

- What It Was Like to Sketch the Trump Trial

- What the Polls Are Saying After Trump’s Conviction