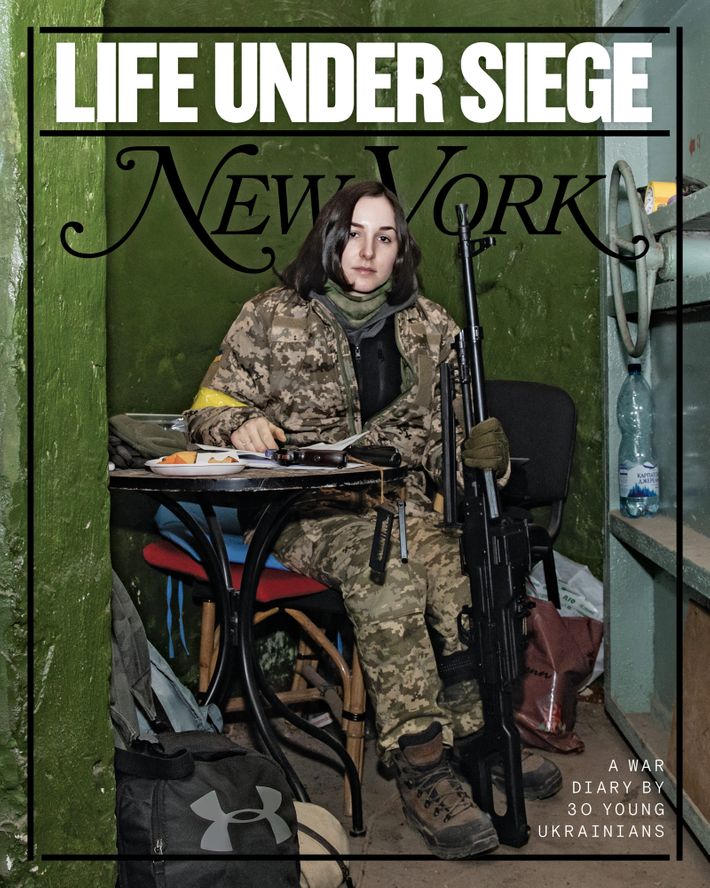

In March, New York published a cover story documenting the first two weeks of the war in Ukraine, entirely from the perspectives of Ukrainians under 30. The 30 contributors to the War Diaries included Anastasiia Mokhina, 24, who appeared on the cover in fatigues and holding a rifle. Her boyfriend had proposed to her two weeks before Russia’s invasion; hours after the first bombs fell, they were both at an enlistment office. New York spoke with her again in mid-April.

.

Anastasiia Mokhina, 24, an email marketer in Kyiv.

We planned to get married before the occupiers started to flee, but my father and part of his unit were sent to the Kyiv region, and my fiancé was assigned to guard a strategic site. No one knew in advance when our forces would return, so the day they did, we called headquarters and agreed on a wedding date — April 7. There was only one day to prepare, but we had an army of helpers. My mother, who is in western Ukraine, ordered a cake, a bouquet, and a head wreath, and my brother found a box for the wedding rings we had managed to order. Our comrades in arms organized a venue — a café — and flowers, Champagne glasses, and a car that drove us all day. The battalion commander agreed to officiate.

Everyone who could make it came to the wedding. There were a lot of our comrades in arms, friends who serve nearby, old acquaintances who are also fighting. Of course, there was my father, because we were waiting for his return the most. And one of my best girlfriends was able to come. That’s why I didn’t even have to throw the bride’s bouquet, as she was the only other woman at the wedding. We had a video chat with my mother, brother, and parents of the groom. They all were sad that they could not come in person, and my mom cried really hard because of it.

We celebrated in the simplest way possible: arrived, took photos, signed a marriage certificate, and allowed ourselves to drink only a glass of Champagne — because even though it is our wedding, we are still at service. Then we went to the café. The meal was great, which in itself was a joy. Instead of wine, there was juice. Then the cake and back to the service. We had a night off but returned to the site we guard, because all of our belongings are there and it is hard to be at home — it evokes many prewar memories. Nobody is waiting for us there.

My husband’s name is Vyacheslav. He is a programmer. We met about five years ago. Motorcycles brought us together — a hobby we have in common. We even traveled around Europe on a motorcycle together: I’m a passenger; he’s behind the wheel. Happy, carefree times.

We did not ask for any days off because we understand that while we are resting, someone has to work harder. We didn’t think about the honeymoon, and it will likely not happen. Yes, the war will end, and we will definitely win, but then we need to rebuild everything destroyed, to restore normal life not only for ourselves but for millions of people. After the victory, I want to get a gun permit and continue training because while this war will end, there is no certainty that one morning soldiers will not come to our land again to kill us.

My husband and I agreed that we will get a dog. I really want a Doberman, but I can’t help but think that there will be a lot of abandoned dogs, so maybe we’ll give a home to one of the puppies. We want children, and often talk about it, but only in a free and independent country.

.

Danyil Zadorozhnyi, 26, a poet and journalist in Lviv, featured heavily in the War Diaries — volunteering at the local train station for 15-hour days and adopting a pet rat, among other activities.

As soon as they let people get married here, we’ll be next. We’ve been at the civil-registry office a few times, but they won’t let us do it without documentation — it’s difficult to prove that my partner, Yulya, is in the country legally. A second reason is that all men, if they want to get married, have to go to the military commissariat and register. They could mobilize me, and that’s just not part of my plans. I know what I need to do.

We’re not volunteering at the train station anymore. I found a job at a publication called Graty that writes a lot about the war. I translate from Russian to Ukrainian and from Ukrainian to Russian, and I write my own things. The job takes a lot of time, and choosing between one thing and the other, I thought, Well, it’s not volunteering, but it’s part of the one great effort for victory. So I feel that I’m still doing something useful — and also making a living, because you have to live on something.

There’s still a stream of people arriving in Lviv, but it’s not as catastrophic as in the first two weeks, when it was just unclear whether the Russians were going to conquer everything the next day or not. And there’s just no more room in the city — it’s really difficult for us to take people in. We were trying to find apartments for people, and it’s just impossible. Some real-estate agents are hiking up prices by an extreme amount and charging enormous amounts of money, which we’re trying to fight. Everyone is shocked — it’s a really big problem. The government calls it profiteering.

Not that much has changed since March. But the language question is more acute now. Some establishments put up signs saying you should switch to speaking Ukrainian, and sometimes they’re very rude — it’s not a request. That really bothers me. If I walk into a place and see a sign like that, I get into an argument with the management, the servers, asking them to take down those signs. Because that way, they’re not Ukrainianizing people but scaring them away.

I went to a first-aid training. They told us what to do if you’re in a place that gets hit with a shell, how to save yourself, what kinds of wounds you might sustain, because they’re specific — like what happens if it’s shrapnel or something else. They explained all of that to us and told us about journalists in certain spots who had survived and those who hadn’t and why. At the end, we were given these first-aid bags. They taught us to bind wounds and explained how to talk to people. That’s important. If a person is lying here, you have to ask if they’re conscious, and if they’re conscious, you ask if you can take a look, where the pain is. We were taught how to quickly apply a tourniquet and what to do in case of severed limbs.

We sleep a lot because there’s a sense of immense fatigue due to everything that’s happening, and there’s the clear understanding that it will be like this for another month, unless it gets worse. It’s probably not going to get better.

As far as I know, Seryi the rat is okay. His owner came to pick him up and take him to Poland. She offered to leave him with us, but it’s a really big responsibility because we would have had to get a bigger cage — and another rat, because he can’t be alone.

.

Viktoriia Khutorna, now 25, was working in Kyiv as a television journalist when Russia invaded. Dodging soldiers on the roads, she fled to a relative’s home nearby and then to western Ukraine. In her last entry, Khutorna described abruptly losing phone contact with her mother in Ivankiv.

Some of my friends have gone back to Kyiv, but I’m still here in the same apartment we’ve been in since March 7. I wake up late, like 10, 11 a.m., because I have trouble sleeping. Then we work all day. At night, we might watch something — I’m into TikTok, to be honest, because I can’t focus on something longer. The only shows I can watch are ones that aren’t set in the present. If it’s in the 19th century, it’s like, Okay, it’s imaginary — I don’t need to think that someone is living their life while I’m not.

I have this syndrome: survivor’s guilt. When I saw the first photos from Bucha and Irpin and I read all these reports of shooting people, raping kids in front of their parents’ eyes, I just couldn’t process it. I understand it’s true, but it’s very difficult to fully integrate it. I was talking to my friend about how I wondered if I should join the Territorial Defense. But these thoughts are more emotional than logical. I know I wouldn’t be any good there. I don’t know anything about weapons or how to shoot.

I mean, even before the invasion, when I heard stories about things like rape, it was difficult to process. I thought that even if a war started, these things wouldn’t happen because people are more educated than they used to be. But the Russian troops have no dignity. I’ve stopped calling them people. They are not people. They are something else.

Once a week, I meet with my therapist. I started talking to her when it had been more than 20 days since we’d heard from my mom and I felt I might lose myself in all of this. It was very unexpected when she finally called. For several days, I had lots of calls from unknown numbers for many reasons, and I never thought it was my mom. But the day when she called, I knew it was her. I started saying, “Mom, Mommy, Mommy?” The first thing I asked was how is she doing — is she okay? Is she safe? I asked if Russian troops had come to our house and if she had food and electricity. Just basic questions about basic human needs.

The day she called was March 28. It was two days before Ivankiv was de-occupied and Russian troops left the Kyiv region. She went to a high building to call from the balcony because people had realized they could get a connection there from a Serbian phone provider.

She said that the first week that Ivankiv was occupied had been difficult. Russian troops allowed them to walk on the streets, but they didn’t allow anybody to use a car, and they tried to find people who were in the military. They went to houses and apartments looking for people with tattoos with Ukrainian symbols. In the city, there was no electricity, no water — nothing. But my mother gathered people in her neighborhood to work together. They managed to have a couple hours with a generator, and she found people who could get water. She was living with her best friend, and she is still staying with her in our house. She even managed to do Pilates every day. This woman, she’s incredible.

.

Mariia Shuvalova, 28, a Ph.D. candidate and instructor, left Kyiv for the Khmelnytskyi region in western Ukraine. In the War Diaries, she recounted a Russian agitator infiltrating her apartment building’s group chat and telling residents that they will die, buying bulletproof vests and other supplies, and wishing she could adopt a cat and name it Bayraktar, after the type of drone the Ukrainian military is using to take out Russian tanks.

I’m slightly scared to go back to Kyiv. The Lithuanian Embassy is coming back to Kyiv, and my gym is opening again. I saw it the other day on Instagram. It’s pretty strange. When the war started, they donated all their equipment, like those fancy bands that are supposed to make your ass bigger and all that — they gave everything to the army. So there’s no equipment in the gym right now.

My university resumed lectures on Zoom and I just had my first class since the invasion. It was absolutely crazy. When they announced it, I was talking with my colleagues: “How on earth should we do it?” You feel like you have no resources to educate. But we want the students to be sure they’ll be able to graduate, so for me, that was important.

Before the invasion, during COVID, we had a small ritual: We used to join Zoom ten minutes early just to chat, to ask “How was your weekend?” It was important to have these human moments during the pandemic. So we did that again. I was surprised that so many of my students joined. It was the day after we saw the photos of the shooting in Bucha. From the first moment when I said, “Hi, guys, how are you doing?,” a few of my students started crying. I felt that everyone was grieving. We did not have to explain or talk a lot; we just understood. It was unbelievably nice to see them. It felt like a reunion. My students are all around the world. Some are in Canada, some are in Germany, some are in Romania, some are in Kyiv — I could hear shots and bombings through some of their microphones. One of my students is from Donetsk, and she shared that her family’s apartment building was bombed and they stayed alive because they were in the basement.

Right now, it’s hard to keep working. We are physically tired, and the Russians still bomb us every night. Almost all the time, I’m shaking. When I’m working on articles and translations, I always feel that tremor. I lost a few kilograms. I’m losing hair all the time, like a cat.

Before I go to sleep, I watch the news. I want to remember it. Our biggest collective fear right now is that everyone will get tired of the war in Ukraine and will get used to this and forget about it. Sometimes when we are having a certain experience, we really want to get rid of it, just pretend that it’s not part of our lives. But I’m convinced that if I don’t integrate that experience into my life, I won’t change my future. Something like this will happen again if we go back to a nice, comfortable life. Even if we get everything back, the Russian Federation will still be our neighbor. And still there is the propaganda machine; there is imperialist culture. There still will be danger. So I want to remember everything and, when we win, to keep caring about preventative measures. For example, I will never live in an apartment without a basement or without a bomb shelter. That’s crucial.

Another thing that happened: I learned how to buy cryptocurrency. We were buying a really huge number of bulletproof vests and helmets. We were coordinating with different people, and I was the one to make the purchase. There was constant shelling that night. So basically, I was buying cryptocurrency for the first time in my life from my basement, and all the time I could hear huge explosions. I went to my online banking and added the invoice, like I was buying a book or a laptop. But the sum was huge. After that, I received an email from the bank: “Dear Mariia, thank you for using our bank. There is a national regulation requiring us to check whether you are laundering money or are a terrorist.” I was under financial monitoring! At that moment, I thought, Oops, maybe something is wrong with me, because I was transferring one-and-a-half million hryvnias to my crypto wallet.

I almost had a heart attack. The first thing I thought was, I’m going to jail. I’m really law-abiding. My father was a detective, so sticking to the rules was very important. Because of the war, you can transfer only $1,000 at a time. I had to transfer $24,000. So maybe it was money laundering. Random people are sending me money. Maybe that’s illegal! I’m a literary scholar with a small income who is trying to buy weapons using cryptocurrency — I must be going to jail. I thought about all those volunteers who trusted me and sent me funds. And I thought, I will owe all those people so much money.

I called my friend saying, “I think I might have a heart attack. I can’t think clearly. Can you please instruct me?” She calmed me down. Another friend reached out to a lawyer, and another reached a person who’s an expert in cryptocurrency transactions. And everything turned out okay. Now I have an official note that I’m not laundering money and I am not a terrorist.