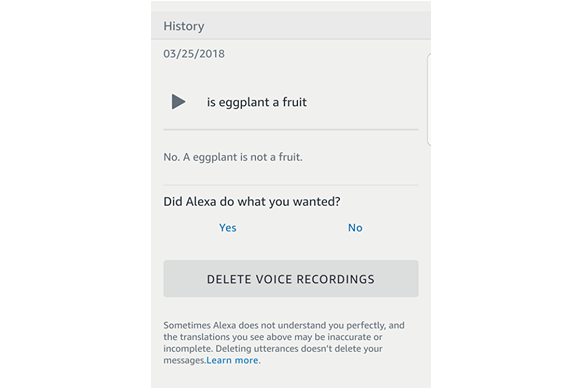

Eggplants, though savory, have seeds, unequivocally categorizing them as fruits. Thanks to Alexa, however, I lost an argument I should have won. While at a friend’s home, I confidently baited Alexa by asking, “Are eggplants fruit?” She replied, “No, an eggplant is not a fruit.” If Alexa can’t outdo Wikipedia, then what’s the use in having one? My 1920s-era apartment is too small to really take advantage of many of the conveniences smart-home assistants can offer. Without an AC unit to preset while I’m at work, a garage to open while I round the block, or a yard to irrigate overnight, for me, Amazon’s Alexa functions primarily as a parlor trick. She’ll entertain guests with a few rounds of Jeopardy!, play Janelle Monáe’s Dirty Computer, and should help me settle debates about fruits that masquerade as vegetables.

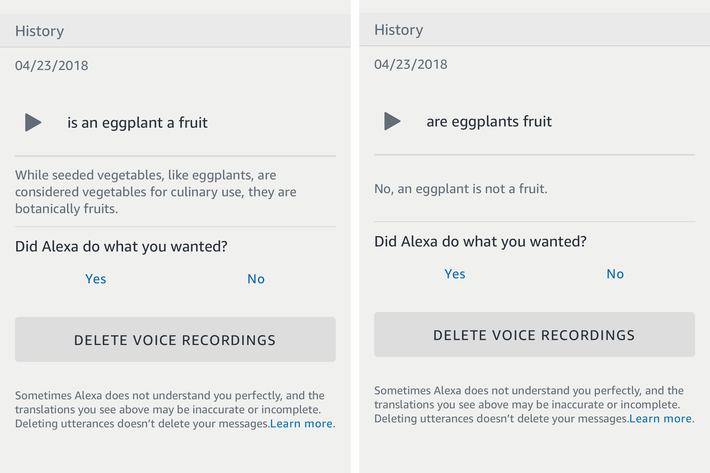

Refusing to believe that I had been mistaken, a quick Google search helped me confirm the truth. But Alexa’s gaffe haunted me for weeks. Nearly a month later, I asked her about eggplants again, this time with a different Alexa device. She gave me a nuanced answer: “While seeded vegetables, like eggplants, are considered vegetables for culinary use, they are botanically fruits.” Why did this other Alexa know the truth about eggplants? It turns out, she wasn’t smarter than my friend’s Alexa, I had just asked a better version of the same question.

When I looked at my Alexa questions more closely, I noticed that a simple change in wording gave me two different answers. My first question had been about “eggplant,” without the article an before it. The second time, I inquired about “an eggplant,” a more proper way to verbally state a noun. While I had originally thought that Alexa had learned the answer to my question and fixed it, I realized that she hadn’t done that at all. The more accurate interpretation was that she had no idea what “eggplant” was, but clearly knew how to define “an eggplant.” I asked again, this time in the plural, eggplants. Though the questions were asked minutes apart, Alexa had already “forgotten” that she knew more about eggplants than I had initially believed.

How the know-it-alls learn

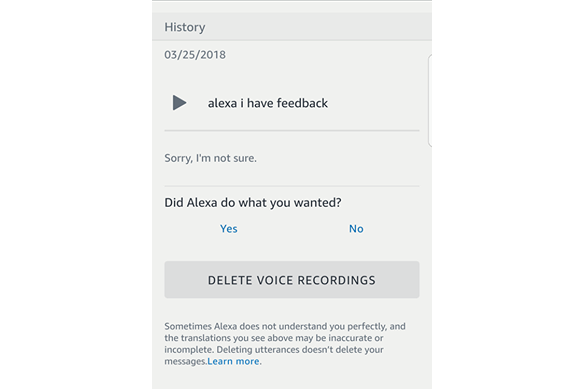

One of the ways Alexa updates her information is through user-provided feedback, but I hadn’t gone the extra step to officially file a complaint. My life wasn’t going to be altered tremendously by the classification of eggplants, but I kept wondering if Alexa had been filling my mind with other incorrect trivia. If she was wrong about this, are Google Assistant, Siri, or Cortana misleading their users, too? I can’t just Google something if I’m not even sure Google is telling the truth.

If Alexa doesn’t have the capabilities to provide a skill or answer, it taps into Amazon’s partnership with Microsoft, which pulls from Cortana and Bing. A representative from Amazon said that Alexa also scrapes information from Amazon-trusted companies like Stats.com, IMDb, AccuWeather, Yelp, Answers.com, and Wikipedia.

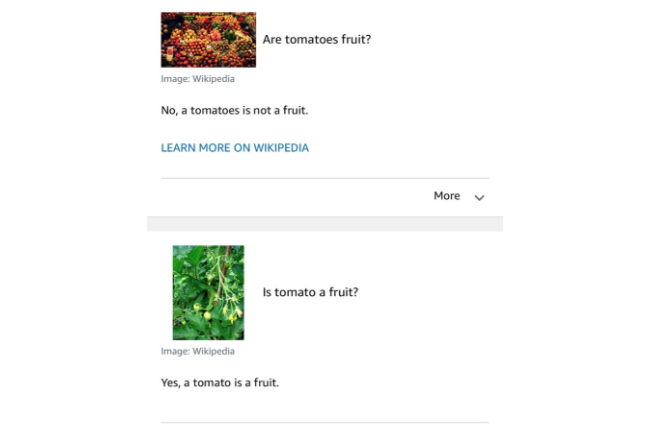

But when I followed up with an Amazon representative about the eggplant discrepancy, realizing that I had unearthed a deeper issue with Alexa’s understanding of language of grammar, they cryptically responded, “Thanks for calling that one to our attention. That’s an error that has since been fixed.” Had I single-handedly inspired Amazon to overhaul Alexa’s understanding of indefinite articles? Apparently not. When I approached Alexa again, this time asking about “a tomato” and “tomatoes,” I realized that she still struggled with the distinction.

I didn’t run into this grammatical problem while experimenting with Google Assistant, Siri, or Cortana — the latter of which was particularly surprising because of Alexa’s aforementioned partnership with Microsoft. While I can’t pinpoint a clear answer without an Alexa programmer opening up about their top-secret code, one possible explanation lies within Evi, the knowledge base and semantic search-engine software that powers most of Alexa’s “Google-able” answers. Byron Reese, CEO and publisher of Gigaom, speculates that some parts of Evi’s knowledge base are updated while others are not. He asked Alexa how many countries are in the world with a minor differentiation in wording, similar to my inquiries about fruit. Alexa first told him that there were 192 U.N.-recognized countries, and then that there were 193 U.N.-recognized countries. South Sudan became the 193rd country in 2011, which means that it’s possible that some of Evi’s knowledge base hadn’t been updated in at least seven years.

I reached out to Google, Microsoft, and Apple to see how their digital assistants process and expand their knowledge in comparison to Alexa. While Microsoft and Apple did not return my request for comment, a Google representative confirmed that Assistant — like Alexa — pulls from a combination of Google-trusted partners and common search results. Both Amazon and Google require potential partners to pass rigorous screening exams that prove that they demonstrate best business practices and regularly update their products. Despite these attempts to verify partners, it’s still possible for dubious sources to worm their way into the top of search results. “Featured Snippets,” the box of text that appears above search results, which the voice-activated Google Assistant reads aloud when answering a question, attempt to give a user the best answer for their search before displaying the full results. The tool can be easily exploited, however. After the 2016 election, fake news started to dominate Featured Snippets, inaccurately claiming that Trump had won the popular vote and that Obama was planning a coup to overthrow the new administration. Last year, Google attempted to remedy the situation by launching a service that updated its Search Quality Rater Guidelines, which better filtered out sources that spread “misleading information, unexpected offensive results, hoaxes and unsupported conspiracy theories.”

These answers point to an ambiguous network of web-content providers who really are the ones making our digital assistants “smart.” Search engines don’t ultimately know anything; they’re curators of knowledge mostly provided by human labor, and the inner workings of the cloud and algorithms shuffle this information around until a broad consensus emerges as truth. In his essay “Google, Words Beyond Grammar,” media theorist Boris Groys explores this with Google’s search engine, stating, “The sum of all displayed contexts is understood here as the true meaning of the word that was asked by the user.” A digital assistant’s knowledge is just a compilation of “all the occurrence of all the words of all the languages through which mankind currently operates.”

So if digital assistants are really just sorting through strings of text written by humans, it’s unsurprising that in order to fix wrong answers, much of the responsibility falls upon the user. Both Amazon and Google’s representatives told me that user-generated feedback can lead to more immediate change in answers, rather than waiting for web content to shift. Our relationship with digital assistants, however, relies on blind trust rather than listening with a skeptical ear, and it’s not a user’s immediate instinct to manually verify everything they’re told. Companies bill digital assistants as seamless, stress-free tools to simplify the daily routine, but also place pressure on the user to question their device’s omniscient knowledge. It echoes the frustration people feel with Facebook’s fake-news problems, in which the company urged users to do their own fact-checking before sharing information.

Our digital assistants are evolving, but until Alexa understands the nuances of grammar and search engines stop presenting fake news, I’m not going to let these products replace the way I absorb new information. Like Zooey and Siri on a rainy day, I’ll still turn to Alexa for the forecast and playing my favorite songs, but I can’t count on her to educate me about the world at large.