Humans have been trying to conquer malaria, Zika, dengue, and other mosquito-borne diseases for centuries. But with malaria alone still claiming more than 1 million lives every year, it’s clear we have a long fight ahead.

But now there’s a new weapon in the war against mosquitoes, and it’s not a vaccine or a new insecticide — it’s aerial drones.

On the east African island of Zanzibar, drones are being used to map the small, often hidden pools of water where mosquitos breed, so they can be sprayed to kill larvae before they mature.

At Rutgers University in New Jersey, engineers are developing “skeetercopters” that can detect and map mosquito-infested sites from the air — and douse them with insecticide.

And now WeRobotics, a technology company with offices in Wilmington, Delaware, and Geneva, Switzerland, has teamed up with the Insect Pest Control Lab of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna, Austria, to develop autonomous drones that will release millions of sterile male mosquitoes over areas where mosquito-borne illnesses like Zika fever are endemic.

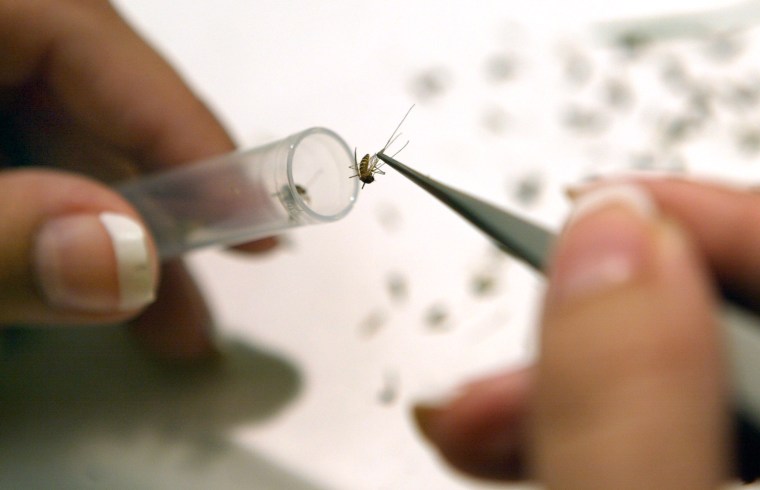

The idea is that the bugs — rendered sterile by exposure to radiation — will drive down the number of infectious mosquitoes in an area by causing the females they mate with to lay eggs that never hatch.

Known as sterile insect technique, or SIT, this technique has been used successfully against tsetse flies, screwworm flies, and insect farming pests in many parts of the world. SIT is also used in the U.S. to control medfly outbreaks and the pink bollworm that ravages cotton crops. And in recent years, SIT has been deployed for the first time against disease-carrying mosquitoes.

The sterile mosquitoes are usually released from backpacks carried by ground workers. But bad roads and poor weather can make it difficult to deliver the bugs to remote areas — and that’s where air delivery by drone looks like a better option.

Patrick Meier, WeRobotics’ executive director, says the idea is not to replace ground-based releases but to complement them: “It’s about combining both methods, ground-based and aerial release, in order to have a maximum impact,” he says.

If field trials of a WeRobotics prototype go well next year, drones could eventually be used alongside ground teams in parts of the world where the IAEA works with governments to control mosquitoes.

The prototype drone is designed to distribute about 100,000 sterile A. aegypti mosquitoes over each square kilometer of terrain. The field trials will use arrays of mosquito traps throughout the target areas to check that the sterile bugs stay healthy during and after their drone flight.

Meier says most of the development effort has gone into designing a refrigerated flight container where the mosquitoes are held before their release.

“We need to keep them in what the IAEA calls a sleep-like state, because otherwise if you put 100,000 mosquitoes in such a small box, and if you don’t tranquilize them with chilled temperatures, then they will kill each other.”

A rotating platform below the refrigerated container slowly drops a measured number of sleepy mosquitoes into a holding chamber, where they wake up before flying into the wild.

WeRobotics has modified an off-the-shelf hexacopter for its prototype, which can deliver 100,000 sterile mosquitoes in about 25 minutes, Meier says. But the release mechanism is designed to be compatible with any type of drone, and with any mosquito species.

The first field trials of the WeRobotics prototype drone will take place early next year in an as-yet-unidentified area of South or Central America that is affected by Zika fever, Meier says.

The trials will use bugs sterilized at an IAEA lab in Vienna, but the release mechanism could also be used to distribute other disease-fighting mosquitoes by drone, such as bugs that have been genetically modified so their offspring die while still larvae, and mosquitoes infected with the bacterium Wolbachia, which blocks their ability to pass on diseases like dengue and Zika.