In 1978, Louise Brown helped usher in a reproductive revolution when she became the first "test tube baby," or child born from in vitro fertilization (IVF). This technique provided a means to sidestep various infertility causes, such as ovulation disorders and fallopian tube issues in women, and decreased sperm count and motility in men.

Now, the world is on the brink of another revolution thanks to an emerging technology called in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG, which would allow doctors to develop eggs and sperm from a surprising source: skin cells. These reproductive cells could then be used to create fertilized embryos to be implanted into a woman's uterus (or, someday, an artificial womb).

Related: How Microbiome Science is Revolutionizing Medical Care

The potential impact of IVG on reproduction — and society at large — is staggering. Infertility may become a thing of the past. Same-sex couples could have children that are biologically related to both parents. And the world may eventually see children born with a single genetic parent or more than two genetic parents.

“It will create an option for people who have no options,” says Kyle Orwig, a reproductive scientist at the University of Pittsburgh.

But with this great reproductive power comes great responsibility — and great concerns. In a new perspective paper in Science Translational Medicine, scholars at Harvard and Brown University called attention to the potential ethical and legal issues of IVG.

For starters, how should the law and society view parental rights with these new reproductive arrangements? What happens if someone "steals" another person's skin cells to make children using that person's genes?

"One of the things I've been most concerned about is the use of IVG coupled with gene editing and modification to select specific traits," says George Daley, dean of the Harvard Medical School in Boston and co-author of the paper. That is, IVG may allow parents to create so-called designer babies.

But are we putting the chicken before the egg?

State of the ART

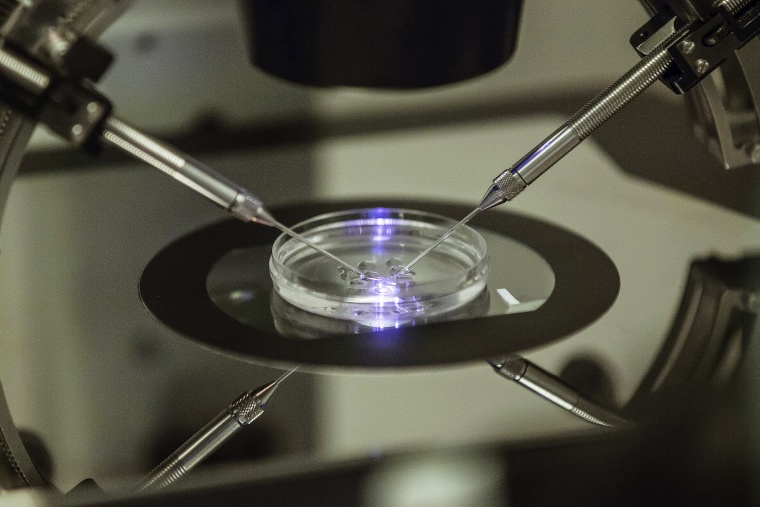

In vitro gametogenesis will be the latest player on the field of assisted reproductive technology, or ART, which also includes IVF and surrogacy. Rather than describing a specific process, IVG refers to the development of gametes (eggs and sperm) in a culture dish (in vitro).

So far, IVG experiments in mice have yielded some remarkable results.

Last year, researchers in Japan created viable eggs from the skin cells of adult female mice, which were then fertilized with naturally derived sperm from male mice. The resulting embryos, created fully in vitro, produced healthy, fertile pups after being implanted into females. Also in 2016, researchers in China used embryonic stem cells to develop sperm-like cells that fertilized naturally derived eggs, eventually producing fertile mouse offspring.

Related: The Quest to Create Artificial Blood May Soon Be Over

"The fact that they could do the entire process in the petri dish is groundbreaking," says Orwig, who's working on a number of IVG projects, including one involving primates. "This has been the holy grail for decades."

Despite the achievement, this type of IVG is not near ready for human use. Turning skin cells into eggs in vitro is a multi-step process, which involves reprogramming the skin cells into stem cells that can differentiate into any cell in the body, coaxing these stem cells into so-called primordial germ cells (the precursors of gametes), and then maturing those cells into eggs.

But this final step currently requires special ovarian tissue. "We got [the tissue] from a number of fetuses taken from pregnant females," says research lead Katsuhiko Hayashi, a stem cell biologist at Kyushu University.

Of course, using the same process in people isn't exactly feasible, so scientists need to find another way to turn primordial germ cells into mature eggs in vitro. A similar thing can be said of the Chinese team's sperm research, which contained steps untranslatable to people. It's near-impossible to predict how quickly science will advance, but Hayashi guesses this maturation issue may be worked out in five to 10 years.

Is It Safe?

Initially, IVG will probably only find applications in research, helping scientists understand things like reproductive cells, embryonic development, and certain inherited diseases, Daley and his colleagues suggest in their paper. Reproductive applications will have to wait until IVG is fully vetted for efficacy and safety, ensuring it doesn't produce babies with genetic diseases or birth defects.

"It's a technology that will come someday, but the question is when and whether it will be completely safe," says Zev Rosenwaks, director of the Center for Reproductive Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

In the meantime, nonhuman primate studies will be invaluable, but Orwig notes that relatively few labs have the capacity to conduct such research. From here, a number of preclinical human tests are necessary, Daley says.

“It will create an option for people who have no options.”

These tests could include the production of embryos with IVG and the derivation of embryonic stem cells, as well as whole genome sequencing on these cells and a full characterization of their ability to differentiate into other cells. "Only then, when you are comfortable that there is some degree of molecular similarity to naturally derived fertilized embryos, would you feel comfortable with birthing a child with IVG," Daley says.

But in the United States, there are major research limitations on human embryos. The creation and subsequent destruction of human embryos from IVG for research purposes would make studies ineligible for public funding, and in some states outright illegal.

These hurdles could suggest that people wanting IVG procedures may be forced to look outside the United States, but Sonia Suter, a law professor at George Washington University who has previously written about the potential benefits and harms of IVG, doesn't think that's likely.

"If anything, I think it will go the other way around," Suter says. "We have too few medical restrictions on reproductive technologies and people often come here to take advantage of that. ART is sometimes described as the 'Wild West.'"

Ethical and Legal Questions Abound

Experts believe IVG will eventually become safe enough to clear regulatory obstacles. Then it becomes a question of how we employ the technology.

Naturally, IVG would be used to restore reproduction in people with incurable infertility issues, such as those due to cancer and chemotherapy, but Zev Rosenwaks doesn't foresee it replacing natural human reproduction in fertile people. Still, some may prefer to use IVG to have babies from embryos that are prescreened for genetic diseases, which may ultimately reduce the levels of disability in society, Suter says. Also, IVG won't do away with traditional IVF, but it may revolutionize the field, making egg donors obsolete, eliminating the need for hormonal stimulation techniques, and ultimately reducing costs.

Related: This App is Revolutionizing Diagnoses of Rare Diseases

Overall, the biggest demand for IVG may come from same-sex couples, Suter says. She and Hayashi of Kyushu University have received numerous inquiries from gay and lesbian couples wanting children with both parents' heritage. This application, however, may come a bit further down the line, as there are additional technological issues to work out. "I would say this is not impossible," Hayashi says. "But technically it is very difficult."

Other IVG uses may raise thorny ethical and legal questions, Daley says.

For example, IVG may eventually allow three people in a polyamorous relationship (a "thruple") to all become genetic parents of a child. For this to work, two people would create an embryo in vitro and cells from that embryo would be used to generate a gamete, which would be combined with an egg or sperm from the third person to create another embryo for implantation. But what happens if the thruple splits?

Additionally, IVG may allow for single-parent babies (one person produces both sperm and egg). But should this application be legal? This "incest on steroids," as Suter puts it, may never come to fruition because it increases the risk of certain types of genetic disorders.

Then there's the question of designer babies. Today, IVF produces a limited number of embryos, which can be screened for serious genetic defects before implantation. With IVG, parents could use their skin cells to produce an unlimited number of embryos — they could then choose which embryo to implant based on traits unrelated to health. This issue could be exacerbated if IVG is combined with gene-editing tools.

Suter suggests this use of IVG may have another unintended effect: enhanced social disparity. If only the wealthy have access to the technology, the argument goes, they'll be able to produce children with improved physical or mental traits that better set them up for success. "It's an age-old problem," she says. "Those with more are able to produce children with more."

Related: Dust to Dust: Composting Corpses in a Greener Future

In their paper, Daley and his colleagues also mention the scary potential of unknowingly becoming a parent — because someone else used your shed skin cells to make gametes. One could imagine a future in which babies are created from genetic material taken from a celebrity's hotel room. Should this "theft" be punished? Should someone have to pay child support for their illegitimate children?

Rosenwaks, however, isn't too concerned about the potential ethical and legal issues with IVG. "I think some of this is possibly over-worrying," he says.

But, Daley suggests, these provocative ideas are still worth thinking about: "It's an important exercise to consider these issues before they are technologically possible."

For more of the breakthroughs changing our lives, follow NBC MACH.