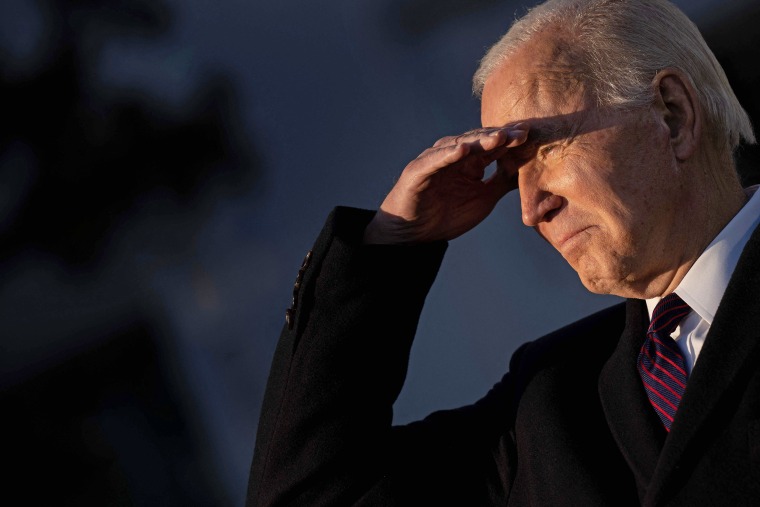

Whenever President Joe Biden has been asked of late about his political future, his answer has been virtually the same.

“My intention is that I run again. But I’m a great respecter of fate,” Biden said at a news conference last month, echoing his answer in an earlier “60 Minutes” interview.

What came after that “but” is at the root of why many observers, particularly in his party or in the press, still treat his 2024 campaign as an open question.

In explaining what Biden means when he invokes the hand of fate, multiple associates point to the moment 50 years ago this Sunday that has proven to be an inflection point in his personal and political life — the accident that claimed the life of his first wife, Nelia, and infant daughter, Naomi.

Biden had just won an upset election to become one of the nation’s youngest senators, emerging as a rising star in a party that had just seen its presidential candidate suffer a landslide defeat. In an instant, Biden went from plotting his next political steps to considering quitting the Senate before he’d even been sworn in.

The president has since spoken often of what came next, and how it reshaped the political career to follow. He would be convinced to serve in the Senate and be mentored by giants of the chamber at the time, learning important lessons about bipartisanship that guided his work there for decades to come. It fostered an empathy and compassion that has proven to be, as his aides often call it, a political “superpower” — particularly in an increasingly cynical political era.

But less appreciated, Biden’s closest associates say, is how that moment a half century ago offered an ambitious politician something that has proven especially important in his presidency so far: perspective on what really matters, and an appreciation for what one can’t control.

As one close ally put it, Biden has seen “the most precious things in his life taken suddenly, and violently.” By invoking fate now, Biden is simply acknowledging that the decision may ultimately be shaped or altered by events or circumstances in the coming months he can’t predict now.

“He knows he can make plans, and make announcements, but fate can intervene,” they added.

For most of the last 48 years, members of the Biden family have gathered in Wilmington to quietly mark the somber anniversary, as they did a year ago and will again this weekend.

Adding to the emotion of the weekend will be another stop Friday, when Biden speaks at the Delaware National Guard facility named for his late son, Beau, for a town hall on new legislation he signed to benefit service members who’ve suffered the effects of toxic burn pits.

Months after being reelected as vice president in 2012, Biden and his team were in the early stages of plotting a 2016 campaign when he learned Beau was given essentially a death sentence, diagnosed with a brain cancer he has attributed in part to his service in Iraq that included extended exposure to a toxic burn pit.

As he traveled the country ahead of this year’s midterm elections, Biden often invoked Beau’s name in discussing the legislation — and at times noted how his son’s promising political future was also cut short. “He should be the one talking to you today, not me,” Biden said at a rally in New York the weekend before the election.

Beau’s death kept him out of the 2016 race, but Donald Trump’s surprise win that year gave Biden an unexpected chance to run again in 2020. Aides now are operating under the assumption he’ll run once more in 2024, despite questions even among Democrats whether he could win four more years.

It’s that electability question that aides also point back 50 years to explain why it’s the last thing guiding Biden’s thinking now.

“He knows what real loss is,” one adviser said.