WASHINGTON — On election nights, the nation is sorted neatly into two colors: red and blue. But the binary approach doesn't do a great job of capturing the beliefs and attitudes of 300-plus million people. There are a lot of nuances out there, as described in the NBC News County to County project.

Last week the Pew Research Center released its latest typology of U.S. political views — nine groups of voters that show at least some of the more refined shades of red, blue and purple in the political environment. The groups were built from a survey asking questions about politics and policy.

The numbers illustrate a few important points about politics in 2021. First, some issues sharply define liberals and conservatives — litmus tests for each side of the spectrum. But second, you don't have to dig too far into the numbers to find the issues that show the internal fissures between the two major political parties.

Pew found four conservative groups in its data.

Faith and Flag Conservatives, the oldest group, strongly support former President Donald Trump and incorrectly believe he won the 2020 election (10 percent of adults). Committed Conservatives are the conservative group with the highest level of educational attainment and are less likely to support another run by Trump for president than other solidly conservative groups (7 percent of adults).

The Populist Right are blue-collar conservatives who strongly support Trump and want him to run again (11 percent of adults). The Ambivalent Right are younger and more diverse than other conservative groups and the least supportive of Trump (12 percent of adults).

Add it all up, and that's 40 percent of the country's adult population.

On the left, there are also four groups.

The Progressive Left is the youngest and most highly educated group of liberals, and they strongly supported Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts last year (6 percent of adults). Establishment Liberals are also highly educated but older and wealthier, and they tend to support President Joe Biden (13 percent of adults).

The Democratic Mainstays are older and more diverse than other liberal groups and also more moderate on some social issues (16 percent of adults). The Outsider Left is the youngest of the liberal groups, and its members were the most likely to support Sanders last year (10 percent of adults).

Together those groups make up about 45 percent of U.S. adults.

And in the middle is the group of voters Pew calls Stressed Sideliners. About 15 percent of the adult population, they split equally between leaning toward the Democrats and the Republicans, although on many issues they tend to side with the more liberal point of view. They are also less engaged in politics and less likely to vote.

There are a lot of differences among the groups and how they see politics, but looking across the data, a few issues stand out as uniting each side. Culture and beliefs are often more important than any policy position — a pattern you can see most clearly in issues of the environment and race.

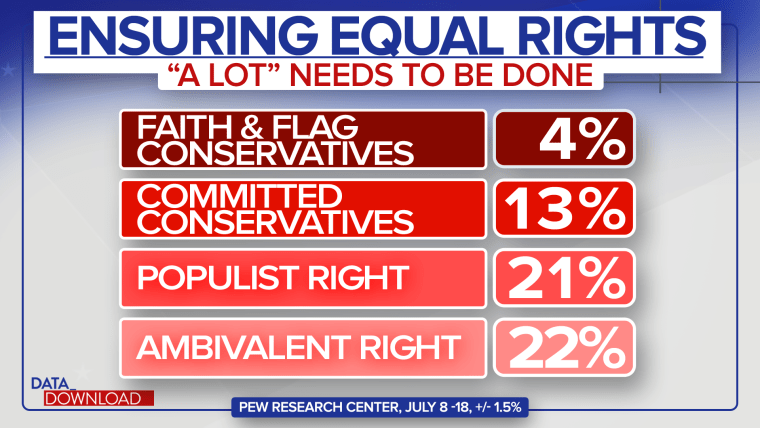

For instance, on a Pew question about "what needs to be done to ensure equal rights for all Americans regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds," the divisions were sharp.

Among all four conservative groups, the percentage of voters answering "a lot" never hit 25 percent. It topped out at 22 percent among the Populist Right and the Ambivalent Right and bottomed out at 4 percent with the Faith and Flag Conservatives.

The Stressed Sideliners were much more evenly divided, with 51 percent saying "a lot" needed to be done.

Among the four liberal groups, there was a strong belief that much still needed to happen to ensure equal rights. The numbers ranged from 73 percent among the Establishment Liberals to a remarkable 96 percent among the members of the Progressive Left.

That's a lot of agreement among liberal and conservative groups, which isn't commonly seen in polling, and it shows the ties that bind the subsets together.

But look at other issues, and fissures begin to emerge.

Consider attitudes toward business profits. There was a time when believing a company "should make all the money it could" was a fundamental aspect of being a conservative. Not anymore.

Among most conservative groups, there is still a solid belief that corporations make a fair and reasonable amount of profit. More than 70 percent of the Faith and Flag, Committed Conservatives and Ambivalent Right feel that way.

But look at the numbers for the Populist Right — they are reversed, with 81 percent saying corporations make too much. For old-school Reagan Republicans, that must look like a typo, but it isn't. The data say about one-quarter of U.S. conservatives are squeamish about the size of corporate profits.

Liberals have areas of disagreement, as well. You can see it in their attitudes toward billionaires, immigration and God.

Among the older Democratic Mainstays, faith in God turns out to be important for leaders; 56 percent say it is essential or important to believe in God to be considered a good and moral person. But take a look at the Progressive Left, three-quarters of whom say belief in God is "not at all important."

A few divides between the groups seem to help explain the differences, including age and educational attainment, but the result is a different set of attitudes about faith and morality.

The Pew Research Center typology is helpful to understand U.S. politics because it is another piece of important evidence that the country may be divided but that politics isn't a simple team sport of people wearing red and blue jerseys. Deeper complexities are lurking in the electorate.

The electorate is always changing, but the level of change in the last 10 years has been seismic. Voters and parties are realigning. And considering the amount of uncertainty in politics today, there's no real reason to expect things to slow down any time soon.