Mpox can have a devastating impact on people with advanced cases of HIV, leading to severe skin and genital lesions and causing death in as many as 1 in 4 of those with a highly compromised immune system.

This is according to the first major study of mpox in this population, which a global team of authors published in The Lancet on Tuesday. The analysis included 382 people from 28 nations, all of whom were HIV-positive and had a count below 350 of key immune cells called CD4 cells, which help ward off infections. Twenty-seven of these individuals died.

“The data is horrifying for people with advanced HIV,” Dr. Chloe Orkin, an infectious disease expert at Queen Mary University of London and the lead author of the study, told NBC News. “It’s really distressing.”

Orkin, who also presented her findings Tuesday at the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle, pushed for people with advanced HIV to be prioritized for mpox vaccination globally. She and her co-authors have also called for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization to designate mpox an AIDS-defining condition when the infection leads to necrosis, or the death of tissue, among HIV-positive individuals.

For people with HIV, a CD4 count of 500 or above is considered healthy. Left untreated, the virus degrades the immune system and leads to advanced HIV disease, although antiretroviral treatment can restore this loss. A CD4 count below 200 triggers an AIDS diagnosis, meaning an HIV-positive individual is at substantial risk of 14 serious and potentially fatal opportunistic infections.

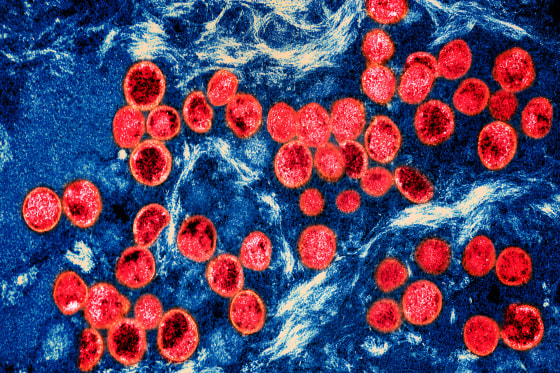

Known as monkeypox until the WHO renamed it in November, mpox was first discovered in humans in 1970 and ultimately became endemic in 11 African nations.

The first signs of the unprecedented global mpox outbreak were identified in Britain in mid-May and in the United States shortly afterward. Globally, there have been 86,000 cases of the virus and 96 deaths in 110 countries, including just over 30,000 cases and 32 deaths in the U.S., according to the CDC. Throughout the outbreak, mpox has overwhelmingly transmitted among gay and bisexual men, a demographic that in the U.S. has an estimated HIV prevalence of 15%.

U.S. mpox cases, the CDC reports, peaked in early August at about 460 per day. Amid a concerted effort to vaccinate gay and bisexual men — nearly 1.2 million doses of the two-dose mpox vaccine have been administered — cases have dropped steadily and have been below 10 per day since late December.

Globally, mpox diagnoses have similarly declined, according to the WHO. However, many cases may go undetected.

Studies have found that 38% to 50% of people diagnosed with mpox were HIV-positive.

The new Lancet paper complements a smaller CDC study published in November of 57 cases of people hospitalized with mpox, 43 of whom had untreated HIV. Because of severe outcomes in people with AIDS, the CDC called for early antiviral treatment of mpox for this group in particular.

Otherwise, most previous research on mpox outcomes in people with HIV had concerned those with well-treated HIV and generally healthy immune systems (antiretroviral treatment can suppress the virus to an undetectable level and allow people to live healthy, long lives). For that population, having HIV has typically not been associated with worse outcomes compared with being HIV negative.

These studies indicated that the mpox outbreak was overwhelmingly driven by sex between men, and that anal sex in particular was likely the central driver.

In the new Lancet paper, the investigators describe how people with advanced HIV were at high risk of a severe form of mpox in which excruciatingly painful lesions on the skin, genitals and mucous membranes were large and widespread and led to necrosis. Some of these individuals also developed unusual lesions in their lungs and even respiratory failure. Also common were bacterial infections in the skin and bloodstream.

In addition to Orkin, the new study was led by Dr. Oriol Mitjà, an associate professor in infectious disease at University Hospital Germans Trias in Barcelona, Spain. Orkin and Mitjà each led one of the two major analyses of mpox-infected people published in mid-summer 2022 that helped identify the outbreak’s contours and drivers.

Among the 382 people with advanced HIV in the study, there were 367 cisgender men, four cisgender women and 10 transgender women. Two-thirds of them were taking antiretroviral treatment for HIV and half had an undetectable HIV viral load.

Of the 179 people with a CD4 below 200, 15% died, including 27% of the 85 people with CD4s below 100. None of those with CD4s at 200 or higher died, nor did any of the 42 people who received the mpox vaccine, including five who received it after their mpox diagnosis.

Compared with those with a CD4 count above 300, those with a count below 100 were much more likely to have skin lesions leading to necrosis, impacts to the lungs and other infections and sepsis. Those who had a high HIV viral load of 10,000 or above also had more severe health outcomes; 30% of this group died.

All those with mpox, Mitjà said, “should be tested for HIV at the time of their diagnosis, and if immune suppression is detected, intensified management should be implemented to attenuate complications in this vulnerable group.”

These concerns are particularly acute, he said, in nations such as the U.S. and Mexico where the proportion of the HIV population not on antiretrovirals is higher than in other regions. According to CDC data, only about half of the estimated 1.2 million people living with HIV in the U.S. have a fully suppressed viral load thanks to antiretroviral treatment.

The Lancet paper’s authors note that the study cohort members may not be fully representative of those with advanced HIV and mpox globally. The cohort may have been biased toward those with more severe outcomes, because people with milder or asymptomatic cases may not have made contact with health care systems.

Dr. Boghuma Titanji, an infectious disease specialist at Emory University who has treated many people with mpox, said, “The study provides much needed confirmation of patterns clinicians treating mpox patients have seen on a smaller scale in their practice.”

In a statement, Dr. Meg Doherty, director of global HIV, hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections programs at the WHO, said The Lancet paper “makes a very compelling case” that mpox “behaves like other opportunistic infections.” The WHO, she said, “will review relevant data with global experts to assess if severe mpox in people living with HIV is a marker for advanced HIV disease.”