The nation’s LGBTQ research field is collapsing.

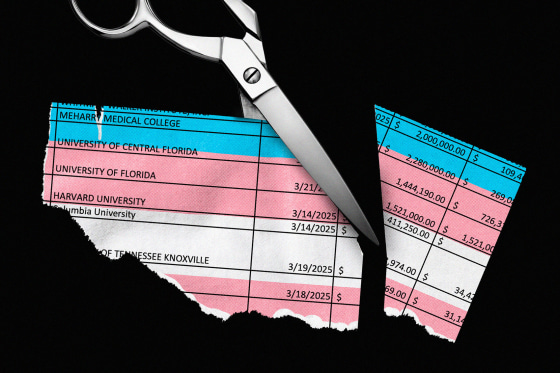

In recent weeks, academics who focus on improving the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer Americans have been subjected to waves of grant cancellations from the National Institutes of Health. More than 270 grants totaling at least $125 million of unspent funds have been eliminated, though the true sum is likely much greater, researchers told NBC News.

Cancellation letters obtained by NBC News often vaguely state that the research in question no longer suits NIH priorities. Some allude to executive orders issued by President Donald Trump, including one that effectively bars recognition of transgender identities and another forbidding diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, initiatives. Other LGBTQ-focused grants have been swept up in the Trump administration’s broadsides against Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania. Academics fear more cancellations as the administration targets Harvard University.

Hundreds of researchers, many of them panicked, have watched as the system that supports their life’s work — to address the myriad health disparities faced by sexual and gender minorities — has been upended. Many of them suddenly face potential unemployment and a job market rendered bleak by the Trump administration’s efforts to downsize funding for academic research.

On Tuesday, mass layoffs across the Department of Health and Human Services included the gutting of programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that surveil the HIV epidemic among gay men in particular, according to a CDC official who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. The Trump administration also eliminated a lab that conducts specialized testing of and assessment for drug resistance among bacterial sexually transmitted infections, including syphilis, gonorrhea and chlamydia, which are especially prevalent in gay men, according to another CDC official who similarly asked to remain anonymous.

“This has been a devastating experience,” said Brian Mustanski, a psychologist and director of the Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago.

Mustanski, a pioneer in LGBTQ health research, built his program into a powerhouse, with his team cultivating some of the most robust data on gay and trans Americans in history. Now, he’s seen much of the institute topple in weeks and has been desperately seeking other positions for many of the half of his 120-person team who were supported by the grants.

The NIH’s new director, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, said in an emailed statement Wednesday that the agency remains “committed to supporting research aimed at improving the health and well-being of every American” but noted that it would be shifting its priorities “away from politicized DEI and gender ideology studies” in accordance with the president’s executive orders.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment. The CDC had no comment.

‘An incredible lack of transparency’

Transgender people face clear erasure from the national research agenda. As for gay people, the White House’s initial, narrow attention on trans populations in its executive orders suggested it might leave gays untouched. But the Trump administration’s justification of NIH grant rejections based on what it perceives as the employment of DEI principles in academia has ensnared many research grants focused on gay populations as well.

This includes research into reducing rates of HIV and other STIs. Such studies have also been canceled if they include trans people as an additional risk group.

Last month, Mustanski said, the NIH canceled two major grants for his team. One supported its long-running study of the drivers of HIV acquisition, substance use and other negative health outcomes in young gay men. Last year, the study, which accrued almost 20 years of data from some participants, received a glowing assessment from the NIH.

The grant was canceled for ostensibly engaging in DEI, according to the termination letter, which Mustanski shared with NBC News.

“It’s unclear how DEI is even defined,” he said. “That’s a big problem for scientists, because science is all about precision.”

Mustanski said his second grant supported implementing effective means of preventing and treating HIV as part of the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative that the first Trump administration launched.

“There’s an incredible lack of transparency behind this process and who’s behind it,” Musanski said of the grant rejections. “That is not the condition that’s going to produce the best science.”

Amid the prospect of both gay and trans people’s erasure from the nation’s research priorities, 30 editors of leading journals that focus on sex and gender research published an editorial last month in The Journal of Sex Research on this work’s importance.

“Research into sexuality and gender is vital for identifying social, cultural, and medical needs of populations, and addressing inequalities across populations,” they stated. “Any limiting of research and forcing specific research agendas is an infringement on academic freedom and integrity.”

“This is what authoritarianism looks like. Fear keeps people silent.”

JULIA MARCUS, HARVARD MEDICAL SCHOOL

Indeed, a clear chill has descended over many of the LGBTQ-focused researchers subjected to — or fearing — grant cancellations. NBC News reached out to more than 80 of them, but few responded and just seven were willing to speak on the record; the others said they were too scared of reprisals from the Trump administration.

“Most of my colleagues are afraid to speak out, or they’re being muzzled by their institutions,” said Julia Marcus, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School.

“This is what authoritarianism looks like. Fear keeps people silent,” said Marcus, who lost all her NIH grant funding for a trio of HIV and STI prevention studies, and shared the rejection letters with NBC News. With the hope for future grant opportunities appearing grim, she said, she faces the end of a 20-year career spent fighting HIV and promoting LGBTQ health.

Any available private funding, from pharmaceutical companies, nonprofits and foundations, could not possibly rescue this overall field, she said.

A quarter-century effort

Virtually all of the nation’s LGBTQ-focused research apparatus has been built over the past quarter century. A notable catalyst was a 2011 Institute of Medicine report that called for greater research into documenting and addressing health disparities among LGBTQ people. The report cited their poorer mental health and higher rates of smoking, substance use disorders, STIs, certain cancers and suicidality.

“Decades of evidence-based LGBTQ+ research has demonstrated the need for specific approaches to improve health outcomes in this community,” said Dr. Philip Chan, an associate professor of medicine at Brown University, who noted he was not speaking on behalf of his employer.

The Biden administration placed particular emphasis on addressing the needs of sexual and gender minorities, and NIH research funds flourished accordingly. Such prioritization, researchers told NBC News, opened increasing avenues for what is known as precision public health or precision medicine, in which research identifies the specific needs of subpopulations and develops evidence-based, targeted interventions accordingly. This, researchers such as Marcus asserted, is the efficient use of public resources at its finest.

NIH-funded research recently scored a landmark win by proving that taking the antibiotic doxycycline following sex slashed STI rates among gay men and trans women — an intervention believed to have driven a remarkable recent turnaround in such cases. But now $7.4 million in NIH support for two follow-up studies, including one on safety monitoring for drug-resistant pathogens, has been eliminated, according to the studies’ lead investigators.

The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network, terminated last month, was in the third year of a seven-year pair of grants — totaling more than $70 million in lost funds — to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of HIV among adolescents and young adults, most centrally young gay men.

“As we talk about government waste and being more efficient, one thing that just really doesn’t make sense is to cut studies that have already invested millions and millions of dollars in their final years,” Chan said.

Chan said he lost two NIH grants last month, totaling about $3 million in unspent funds, and he shared those termination letters with NBC News. One focused on improving the mental health of LGBTQ people negatively affected by the Covid pandemic. The second concerned a program to boost adherence to the HIV-prevention pill, called PrEP, among Black gay and bisexual men.

“Given the overall goal of LGBTQ+ research of not just improving, but extending the lives of LGBTQ+ Americans, the effective dissolution of this research threatens to widen health disparities related to HIV, mental health, substance use, and chronic disease, which will eventually affect everyone in our society,” he said.

Potential elimination from vital government surveys

Ilan Meyer, a professor at the Williams Institute at UCLA’s School of Law, has sounded the alarm that LGBTQ people also face potential elimination from major, ongoing federal surveys regarding health and crime victimization, as well as the census.

“We are about to lose knowledge about the LGBT population that has been essential for understanding policy, for providing advice to litigation, for providing evidence for courts. And to inform the public,” he said.

The inclusion of questions regarding sexuality and gender identity on these surveys has been a hard-fought win for LGBTQ advocates. The resulting data has been the basis of hundreds of academic papers — including some, Meyer noted, that helped persuade a judge to overturn California’s ban on same-sex marriage in 2010.

A new Williams Institute report Meyer co-authored asserted that it “seems likely,” to appease the Trump administration, that future cycles of federal health surveys would eliminate questions on gender identity, and possibly sexual orientation as well. The CDC, for one, announced in February that it would cease collecting data on gender identity in its surveys.

“The removal of such data from the public record and the loss of future data would set the United States decades backward to a time when little was known about the current demography, health, and well-being of the 14 million LGBT people in the United States,” the report warns.

Inside NIH: A department in turmoil

Sources inside the NIH, who requested anonymity because they said they are forbidden to speak to the press and fear reprisals, described an agency thrown into turmoil.

In 2015, the NIH formed the Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office to coordinate LGBTQ research across the agency and, for example, to establish uniform language about sex, gender and sexual orientation across research projects.

The office has been a particular target of conservatives, who allege that it infuses ideological, unscientific perspectives into research. Consequently, Trump’s election in November ignited fears within the NIH that the new administration would gut the office. So in December, the office was effectively dissolved, and its seven staffers were dispersed into open positions where they hoped to continue working quietly in the background, according to two NIH employees familiar with the matter.

On March 4, all seven employees were placed on administrative leave. By that time, the Trump administration had already instituted sweeping layoffs of federal employees who were focused on what it characterized as DEI initiatives.

NIH grantees, meanwhile, told NBC News that their designated agency program officers had been cut out of the loop from their grant cancellations.

“It’s a bloodbath,” one NIH source said of the cancellations.

On Wednesday, the American Public Health Association and others sued the NIH in federal court over canceled grants, including those backing HIV-prevention research. Evidence suggests, the suit asserts, that the cancellation letters were originally developed by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, and not within the HHS or the NIH. The suit states: “For example, metadata associated with at least one such notice shows it was authored by ‘JoshuaAHanley.’ An attorney named Joshua A. Hanley, a 2021 law school graduate, works at DOGE.”

Hanley did not immediately respond to an email from NBC News seeking comment.

Internal guidance issued to NIH grant management staff last week was cited by the lawsuit as evidence of the agency using “boilerplate notices to terminate hundreds of grants.” The document provided language for communicating with grantees, including: “It is the policy of the NIH not to prioritize [select one of the following: diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) research programs, gender identity, vaccine hesitancy, climate change or countries of concern, e.g., China or South Africa.]”

Multiple cancellation letters reviewed by NBC News have stated: “Research programs based on gender identity are often unscientific, have little identifiable return on investment, and do nothing to enhance the health of many Americans. Many such studies ignore, rather than seriously examine, biological realities. It is the policy of NIH not to prioritize these research programs.”

Researchers noted to NBC News that only a few of the canceled grants pertain to gender transition treatments for minors, which has become a political flashpoint.

Even prominent right-wing critics of the agency’s approach to research related to gender identity have taken issue with the Trump administration’s tack of canceling grants.

Leor Sapir, a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, has advocated for NIH reforms that align with Trump’s orders on DEI and trans issues. However, he criticized the administration for its overly broad “search-term-based cancellation” of NIH grants.

“It’s quintessential bull in a china shop — Trumpesque,” he said in an interview. “A much more fine-tuned approach needs to happen.”

The prevailing question facing NIH-funded researchers is whether such a recalibration will occur now that Bhattacharya was sworn in as director Tuesday. During his confirmation hearing early last month, Bhattacharya, a health economist formerly of Stanford, was asked repeatedly whether he would return the NIH to something resembling normal functioning.

“I will follow the laws,” he said — a refrain he relied on for such questions. He added that he would “make sure” that researchers within and funded by the NIH, “have the resources they need to make sure that they do their research.”

In response to questions about the grant cancellations — including one about the Trump administration’s intentions regarding research specific to transgender people — Bhattacharya’s statement Wednesday said the agency would be committed to research that improves the health of all Americans, “regardless of their sexual identity,” though it notably did not mention gender identity.

It then noted that the agency would shift its priorities toward “research aimed at preventing, treating, and curing chronic conditions like cancer, diabetes, heart disease, obesity and many others that cause so much suffering and deaths among all Americans, LGBTQ individuals included.”

The statement made no specific mention of HIV, a chronic health condition that disproportionately affects gay men and trans women. Also not mentioned was that at least 16 of the LGBTQ-focused grants that were terminated concerned cancer, diabetes or heart disease.

The hard work begins

Looking toward an uncertain future, Northwestern’s Mustanski, for one, said he hopes for success in appealing his grant rejections.

Dr. Kenneth Mayer, medical director of Fenway Health, a leading LGBTQ-focused health center in Boston, expressed hope for “some victories in the courts” over the grant cancellations. Noting he was not speaking on behalf of his employer, he added: “But I am not in denial, so the field could collapse.”

Mayer and other LGBTQ-health researchers expressed concern that their field would lose a generation of academics focused on these populations — through layoffs, hiring freezes and the likelihood that bright young people would eschew a newly uncertain career in academia and public health.

Many veterans of this field reported suffering from what they characterize as foreboding déjà vu under the Trump regime.

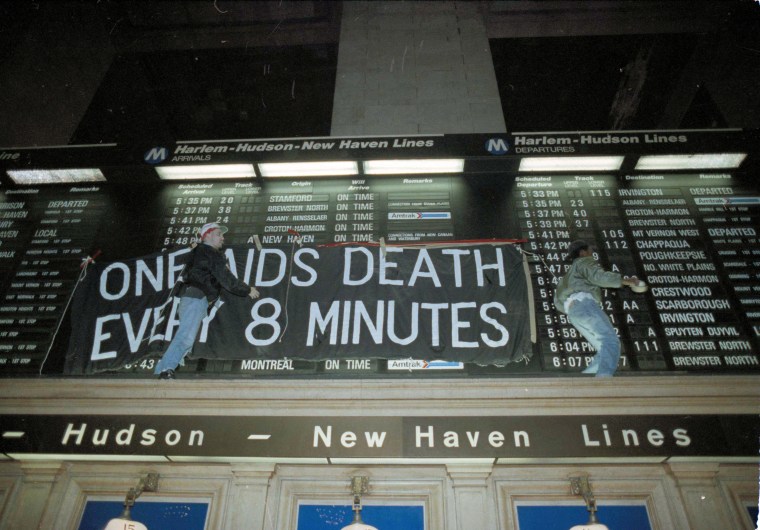

Dr. Chris Beyrer, director of the Duke Global Health Institute, said the past few weeks have reminded him of the horrors he witnessed in the 1980s.

“When I started my career in HIV research, there were really no dedicated funds” for LGBTQ-specific research, he said. Recently, he added, he’s been haunted by that period in his career, four decades ago, when he cared for babies dying of AIDS. This was a time when gay men perished of the disease by the tens of thousands while then-President Ronald Reagan remained largely, and notoriously, impassive.

UCLA’s Meyer, however, struck an optimistic tone when he said that lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans Americans are nothing if not tenacious in the face of political adversity.

“One thing that I tell students is LGBT people have been fighting for more than 100 years for our rights,” he said. “So, I think this just reminds us that we need to continue doing that.”