Ask members of the Filipino American National Historical Society and they will say the Delano Grape strike of 1965 — the grape boycott that neatly tied together civil rights and labor rights in America—should be known as the revolution of Larry Itliong.

Instead, the strike that changed the world’s view on farm labor is more commonly known in history as the movement that made Cesar Chavez an international labor hero.

To mark 50 years since the week after the strike vote by Filipinos (Sept. 7th), and their bold first step to walk off the fields (Sept. 8), nearly 500 people gathered Labor Day weekend in Delano in California’s Central Valley to try and correct the record on Itliong and Chavez.

Among those gathered at Delano's Filipino Hall - the historic site of the strike vote - was Chavez’ son, Paul, who remembered his "Uncle Larry," Itliong.

“There are names lost in history, and today’s ceremony goes a ways to rectifying that,” Chavez, 58, told NBC News. “Of course, there were some hard feelings. Who would not be offended if they felt their contributions weren’t recognized...We should now look to recognize these unsung heroes…Latinos and Filipinos alike.”

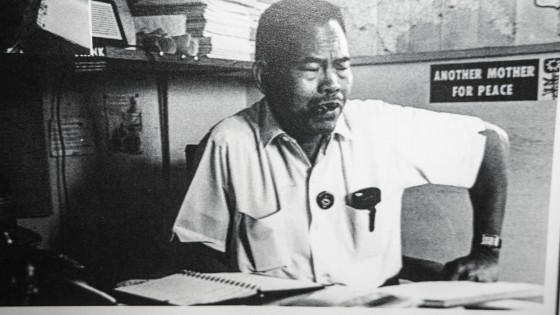

Among the other Filipino Americans often eclipsed in the history books by Chavez’ father were Pete Velasco and Philip Vera Cruz. But if Chavez ultimately became the face of the strike, Itliong was always its heart and soul.

“It’s very important getting him recognized for what he did,” Johnny Itliong, Larry’s son, told NBC News. “He didn’t do it himself, but he initiated it all…How did Cesar Chavez become the founder of a union he was asked to join? That’s on him for creating the fallacy, doesn’t mean he didn’t do any good. Just a matter of setting the record straight.”

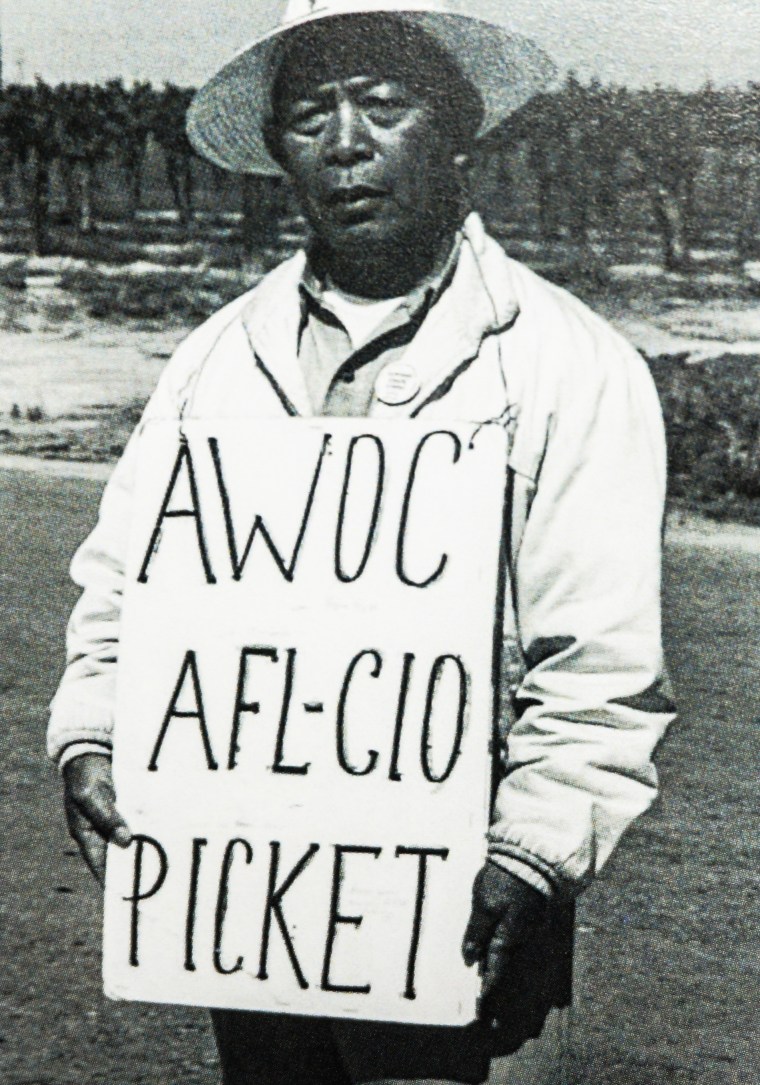

John Armington, now a lawyer, was ten-years old at the time of the 1965 strike. He recalled watching his father, Bob - a Filipino laborer - make the motion to strike in the meeting called by Itliong, then the head of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AFL-CIO).

"Larry Itliong yelled out to the packed hall, 'I want those in favor to stand up with your hand raised,'" Armington said. "Everyone in that hall stood up with their hands in the air. It was a unanimous decision to call a strike against the grape growers in Delano and vicinity."

The walkout began on Sept. 8, 1965 when the growers refused to honor the union’s demand for wages of $1.40 an hour.

That’s when Chavez first heard about the Filipinos in the streets, according to Gilbert Padilla, who was co-founder with Chavez of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). Padilla said the NFWA wasn’t a real union, and that all it could offer Itliong then was use of a mimeograph and some picketing help.

But Alex Edillor, the president of the Filipino American National Historical Society’s Delano Chapter which sponsored the celebration, said Itliong knew the fields were about to go through an evolutionary change. The Mexican migration of workers was exploding. The Filipino work force - now in their 60's and 70's - was aging, most of them having arrived to the U.S. in the 1920s and ‘30s.

“He knew for the strike to succeed the Mexicans were needed to become a larger force,” Edillor said.

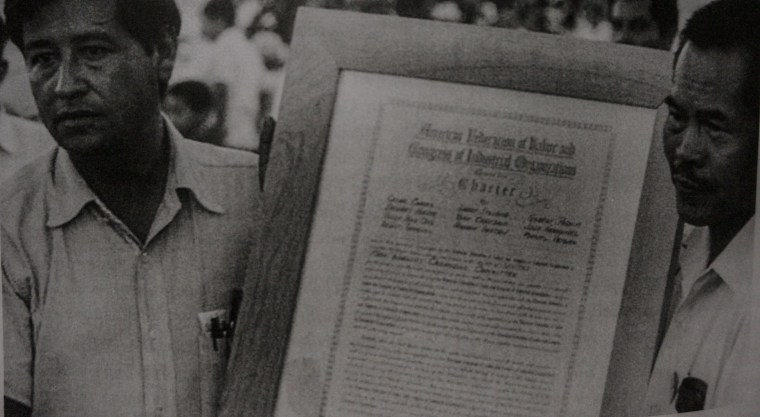

According to Padilla, that’s when the merger talks began.

“He was the one who made the decision for the negotiations between the NFWA and AWOC,” Padilla said, describing Larry’s strength as a strategist and negotiator. “Larry was the one who made sure we merged together.”

"We have to point the finger to ourselves, we haven’t told his story well. But now, we’re trying to change that.”

By Sept. 16, the NFWA voted to join the strike. The eventual result was the United Farm Workers Union, which brought together Filipinos and Mexicans, but also combined the labor movement with the broader civil rights movement. It was a story that would attract newsmakers like Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy to the fields. It drew international attention with Chavez’ hunger strike and belief in non-violence.

Things did change, just as Larry Itliong predicted. The Mexican workforce grew. The number of aging Filipinos in the field dwindled. So did Itliong's influence.

Itliong left the UFW in 1971. Padilla said he begged him to stay, but Itliong said he wanted to do other things. Even before his official departure, young Filipino Americans were already wondering why Itliong and other Filipinos were all too often forgotten and left out of public narratives about the UFW.

Reynaldo Pascua, 65, current president of the Filipino American Community of Yakima Valley (Washington), and administrator of the Yakima FANHS, was just 21 when he visited Itliong in Delano.

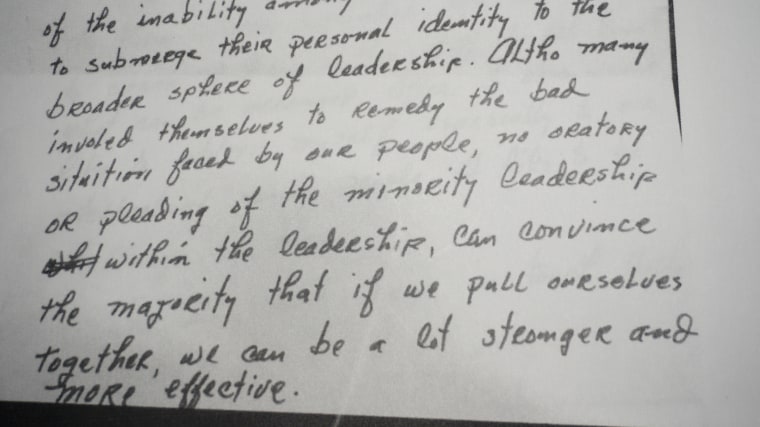

At the Delano event he shared with NBC News a letter Itliong wrote to him on Jan. 22, 1971. The two regularly corresponded, Pascua said, and that letter offered some insight into what Itliong called the “unrecognized hard work of pioneering civil rights for our people.”

“This was because of the inability among the Pinoy leadership to submerge their personal identity to the broader sphere of leadership,” Itliong wrote. “Altho (sic) many involved themselves to remedy the bad situation faced by our people, no oratory or pleading of the minority leadership with the leadership, can convince the majority that if we pull ourselves together, we can be a lot stronger and more effective.”

Itliong resigned as assistant director of the UFW later that year. He later died, in 1977, due to Lou Gehrig’s disease and ALS.

Dawn Mabalon, history professor at San Francisco State, a FANHS trustee and an Itliong researcher said by the time Chavez was getting his full recognition in the ‘90s, Itliong had been dead for nearly 20 years.

“The tragedy is compounded by invisibility of Filipinos in general, from the foreign policy in the Philippines to general labor history in K-12 and college, and it’s an absence in all these places,” said Mabalon. “In 1965, people weren’t thinking about farm workers’ wages, pesticides, organic food, or how workers were treated...The farmworkers movement was a social justice movement. The humblest people showed they can make change and have tremendous power.”

Now, because of the efforts of FANHS and others, there’s a growing awareness of Itliong and his efforts to unite the farm workers.

California’s first Filipino American Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Alameda) passed a bill requiring the teaching of Itliong and farm worker movement. This year, Gov. Jerry Brown declared Oct. 25, Itliong’s birthday, Larry Itliong Day. In addition, a school in Union City has been named for Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, and hopes to be the first to kick off the Filipino education component. Another FANHS effort is being led in Stockton by Dillon Delvo, the son of a former AWOC organizer, to name a street after Itliong in a district known as “Little Manila.”

“Larry is from Stockton, and hardly anyone knows that,” said Delvo to NBC News. “Larry’s been ignored. Fifty years later and most Americans don’t know the Filipino American role in the Grape Strike, including most Filipino Americans. We have to point the finger to ourselves, we haven’t told his story well. But now, we’re trying to change that.”