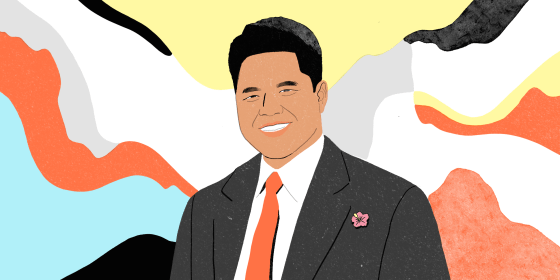

For Jordan Lee, the most difficult part of the coronavirus pandemic hasn't been the 12-hour shifts in the intensive care unit, the extra precautions and safety protocols he now has to follow or even the fear that he, too, may eventually contract COVID-19. It's been the isolation.

As a pulmonary critical care physician at Queen's Medical Center in Honolulu, Lee, 37, said COVID-19 has changed everything about the way he provides end-of-life care to patients and their families. Many of the medical practices and cultural traditions he usually draws upon have been disrupted by the physical distancing that fighting the pandemic requires.

"The loss of human touch is probably the hardest thing," Lee told NBC Asian America.

Before the pandemic, Lee, who was born and raised in Hawaii and attended high school at the Kamehameha Schools, an educational system for Native Hawaiians, had a variety of methods from Western and traditional medicine to comfort patients in the ICU. Most of them are rooted in physical proximity: hugging, holding hands, integrative wellness, healing touch and reiki therapy, as well as bringing the patient's loved ones close to pray and cheer for them.

Now, he said, all those practices are gone. Even as patients die, he said, he can't hold their bare hands — he can touch them only through gloves — and they can't be with their families.

"That's going to have such a large psychological impact on a lot of the patients themselves, should they recover, as well as their families — the isolation and emotional trauma," he said.

He estimates that he's treated up to two dozen patients with COVID-19, representing the "sickest of the sick," at Queen's Medical Center. (Other patients with COVID-19 are in other parts of the hospital, he said.) Often, that includes placing them on a ventilator, a process that he said leaves him "maximally exposed" to the virus because his face, covered only by a N95 mask and a face shield, is in the patient's airways while the patient is breathing and coughing.

Communicating with patients' families, who are no longer allowed in the hospital, has also changed. Normally, said Lee, who's also an assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Hawaii, he uses facial cues and body language to figure out how to compassionately tell families about their loved one's condition. Sometimes, he'll offer a hug.

"That's a really hard part of the job," he said. "The whole art of medicine is how you deliver good news and bad news, and you don't have that ability over the phone."

According to the state Health Department, Hawaii has just over 600 confirmed cases of coronavirus and 14 deaths. The majority of Lee's patients have been Asian Pacific Islander, which he attributes to the demographics of the island, where nearly 50 percent are Asian, Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian and another 24 percent are a mix of two or more races.

The isolation of COVID-19 also affects Lee personally.

At the outset of the pandemic, his mother moved in with him to have greater comfort and safety while sheltering in place. But even though they're living together, they can't be too close, because the nature of Lee's work in the ICU means he always has to assume he has the coronavirus.

"Every time I go to work, it's like, 'Am I bringing it home?' We don't hug, we don't honi honi, or kiss," he said of the traditional Hawaiian greeting of kissing each other on the cheeks. "We just keep our distance but enjoy each other's company and sit separately."

Without that affection, he said, he's missing out on a "very Hawaiian way of day-to-day life."

"That's the part of our shared experience as locals and Hawaiians is the hug and kiss, and now we all resort to air hugs and shakas from 6 feet away," he said.

While Lee said social distancing has helped Hawaii "flatten the curve" and avoid the catastrophic surge that states such as New York have experienced — and he urged everyone in Hawaii to continue maintaining separation from one another — he also knows it comes at a cost.

"It's hard," he said. "It's a different mindset."

This story is part of our Asian Pacific American Heritage Month series, "AAPI Frontline," honoring essential workers who are serving their communities during the coronavirus pandemic. Read more here.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.