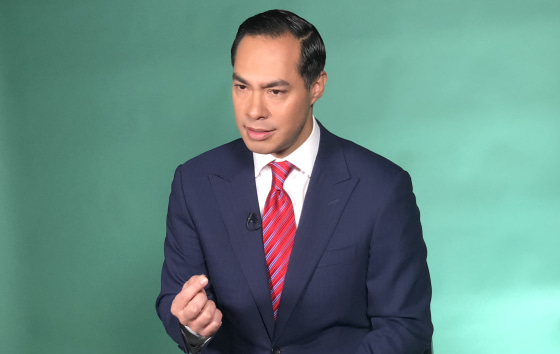

Former Housing Secretary Julián Castro said he is a conversation away from deciding whether to run for president.

It’s a conversation he has to have with his wife, Erica, and their children so he can give a solid answer after the Nov. 6 midterm elections, he told NBC News in an interview on Wednesday.

The buzz has been building since he told Rolling Stone magazine this week that he is "likely" to run for the Democratic nomination in 2020. This February he told NBC News that he had "every interest" in running.

Discussing his just released memoir, “An Unlikely Journey," Castro talked about growing up without money in a multigenerational Mexican-American household in San Antonio.

Castro pushed back on a book review that said he hadn't confessed to anything revealing in the memoir, explaining that as a young Latino from an impoverished neighborhood, he was very aware of how his life choices would be perceived.

“The place that I came from, the neighborhoods that I came from, not a lot of people got second chances," Castro said. "You couldn’t count on a second chance.” San Antonio’s West Side, which Castro describes in the book, was an area of high poverty with fewer city resources, though it was culturally rich.

“Today in politics people almost assume that if you don’t confess to being terrible in your youth that something’s wrong," he said. "I wanted to make the most of my first chance.”

Castro was a motivated, accomplished student — except when he had to take music, which he jokes wasn't his strong suit. He didn’t drink because, growing up, he and his twin brother, Joaquín, had seen their mother struggle with alcohol, as he reveals in his book.

Along with serving in the Obama Cabinet as housing secretary and as the mayor of San Antonio from 2009 to 2014, Castro made Hillary Clinton's short list of potential running mates in 2016. He doesn't address in his book Clinton's decision to bypass him for Sen. Tom Kaine of Virginia in a year when many thought adding him to the ticket would have helped Democrats with the Latino vote.

The book is lightly sprinkled with Spanish as he describes growing up with his Mexican-born grandmother and his U.S.-born mother. Castro said he wasn't trying to counter Republican rivals who have questioned his Latino identity because he is not a native Spanish speaker. Instead, it's a reflection of how he grew up, with a grandmother who spoke Spanish and English and used both with him and Joaquín, and a mother who also was bilingual but was punished for speaking Spanish in school.

"People have this odd way of gauging whether somebody is Latino or Latina enough and I don't know why that is," he said. As children, he and his brother attended a language school where he took Japanese and his brother took German, he writes in his book. Today, his daughter is in a bilingual school, using English and Spanish.

"I think that says something about our country that ... we could go from a country that punishes Spanish speaking to a country that celebrates learning another language, whether it's Spanish or another language," he said. "That is a sign of progress."

It also says something about the moment the country is in right now, he said.

"It crystallizes whether we are going to move forward and be a nation that tries to understand each other, tries to expand opportunity for everybody or one that goes backward and becomes more divisive and xenophobic and myopic," he said.

Castro alluded to what his presidential platform might look like if he were to run against President Donald Trump in 2020. Some of it is captured in the book’s intriguing subtitle — "Waking Up From My American Dream."

Although it sounds like an angry indictment, Castro explained what the subtitle means in his trademark calm way, somewhat reminiscent of former President Barack Obama.

“We realize that it’s not enough to just work hard, for your family to work hard in order to achieve the American Dream," he said. "Often, you also have to make your community and society better.”

Castro and his brother, a fellow Democrat who has represented the San Antonio area in Congress since 2013, grew up steeped in their mother's activism, born from their grandmother's tough childhood and limited trajectory in life.

His grandmother arrived as an orphan from Mexico, when signs that read “No Dogs, No Negroes, No Mexicans” could still be seen in Texas. The relatives she lived with didn't give her a choice; she started cleaning homes as a young child, and she would the rest of her life.

Castro's mother rebelled against what she saw as discrimination and bigotry; when she accompanied her mother to clean a house, the family tasked them with taking the ticks off the family dog.

Castro's mom, who was smart and inquisitive, became a Chicana activist, worked to get a Master's degree and has been involved in political and civic campaigns for most of her life. Though they grew up in limited economic circumstances, the family emphasized education and involvement.

“For my brother, Joaquín, and me, public service has always been about trying to make sure that folks who come from disadvantaged backgrounds can also achieve their dreams,” he said.

The current administration is instead taking opportunity away from a lot of people, he said.

“I’m glad to see that a lot of this young generation also is woke,” he said, "whether it’s the March for Our Lives, student activists or any number of young people that are doing fantastic things to push back this administration.”

He said he thinks the Democrats will win Congress in November.

A continuous thread in Castro’s memoir is educational opportunity. Although he and his brother were stellar students who attended Stanford and later Harvard Law, they learned at Stanford about the inequality of their high school education compared to many of their college peers.

In the book, he recalls that he and Joaquín did not know how to use a Mac computer because they’d never used a mouse.

Although Joaquín figured out that a mouse moved the computer's cursor, another student had to tell them to turn it over because they were using it upside down.

Castro writes about unequal education opportunities, adding, “I’ve tried to take the attitude we can do something about it.”

When he served as mayor of San Antonio, Castro won public support for a city sales tax increase to significantly expand high-quality, full-day preschool, a big help to the city’s young Latinos.

“For the Latino community, it’s important that we elect representatives at every level that believe in investing in public education," Castro said. "The community still lags behind when it comes to educational opportunity," Castro said.