Black-white biracial sons of interracial parents, in which one parent is black and the other is white, are more likely than their female counterparts to identify as black, according to a study found in the February issue of the American Sociological Review.

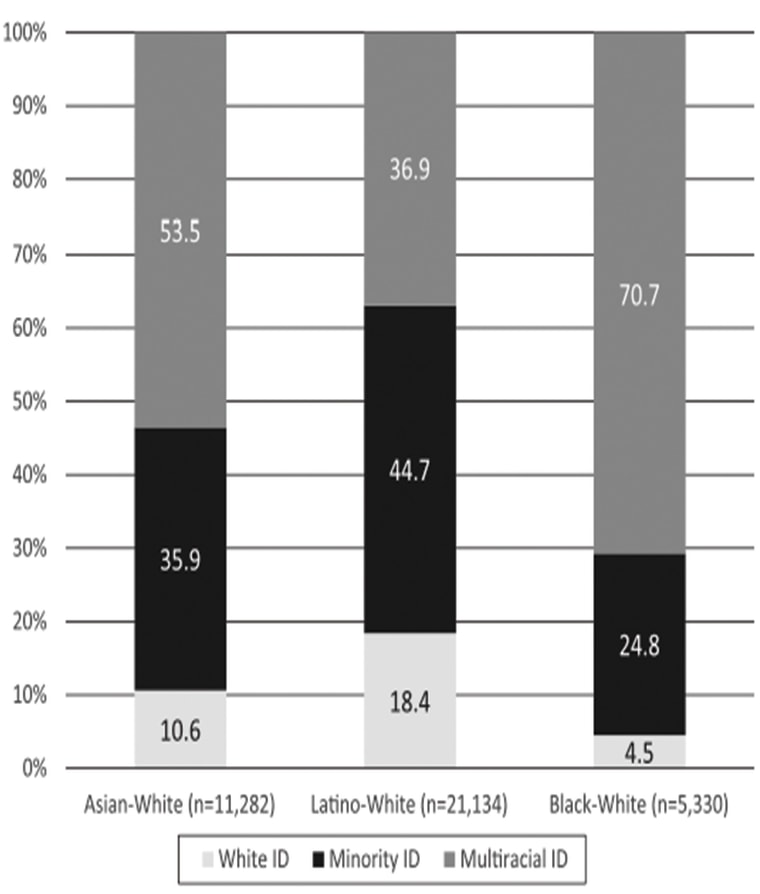

In a sample of more than 37,000 students from the Cooperative Institutional Research Program (CIRP) Freshman Survey, data pooled from the 2001, 2002, and 2003 surveys revealed that 76 percent of black-white biracial women identified as multiracial, whereas only 64 percent of black-white biracial men identified as multiracial.

"I argue that the different ways that biracial people are viewed by others influences how they see themselves," said Lauren Davenport, an assistant political science professor at Stanford University who produced the study. "Biracial men may be more likely to be perceived as ‘people of color.’”

For instance, President Barack Obama, who identifies as an African-American though he is as equally the first black U.S. President as he is the 44th white President. “I identify as African-American - that's how I'm treated and that's how I'm viewed. I'm proud of it," Obama has said.

Once known by many as the whitened “Barry” nickname in his grammar school years, Obama discusses how he began to identify as member of the black community and why he opted for Barack when he was 19 in his first book, Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance.

“When people who don't know me well, black or white, discover my background (and it is usually a discovery, for I ceased to advertise my mother's race at the age of twelve or thirteen, when I began to suspect I was ingratiating myself to whites), I see the split-second adjustments they have to make, the searching of my eyes for some telltale sign," Obama writes. "They no longer know who I am.”

Although he began to refer to himself as black, he divulges that his racial designation was not solely his decision.

However, Davenport contends that biracial women are more likely to identify as multiracial because they "are often seen as not fully white and not entirely minority, and they are cast as kind of a mysterious, intriguing ‘racial other.’ As a consequence, it may be easier for women to reside in multiple racial groups simultaneously."

One instance was the overwhelming reaction from the black community in response to Beyonce’s 2012 L’Oreal commercial advertising a foundation called True Match. She stated in the commercial, “There’s a story behind my skin. It’s a mosaic of all the faces before it. My only make-up? True Match.” This statement plays in the background as the words describing Knowle’s heritage enter the screen: “African-American, Native American” and “French.”

The underlying message of the advertisement was to promote a product that provided coverage to a diversity of unique undertones, in which case it would seem logical to provide a more extensive list of Beyonce’s ancestry. Yet, in contrast to Jennifer Lopez describing herself as “100 percent Puerto Rican” in her True Match commercial, Beyonce’s depiction appeared to be distancing herself from the black community.

Factors such as religion and socioeconomic status can also play influence on how black white biracials label themselves. Davenport found that, “relative to biracials who were religiously unaffiliated, those who identified with ethnically homogeneous religions were more likely to label themselves with a single racial category, than as multiracial.” Consequently, black-white biracials who also identified as Baptists were 44 percent less likely to label themselves multiracial in contrast to black-white biracials who weren’t religiously unaffiliated.

RELATED: Biracial in the Time of Black Lives Matter

“I also found that money ‘whitens’ racial identification for biracials,” said Davenport. Of the students surveyed, black-white biracials from the most affluent households, in contrast to those from poorer communities, were more likely to identify as “white” or multiracial than that of their minority parent. From these findings Davenport concluded, “for the growing mixed-race population, racial labeling choices are intimately linked to social group attachments, identities, and income.”

And despite the colonial-dated “hypodescent” rule, otherwise known as the “one drop rule” that asserted anyone with African ancestry was wholly black, the study uncovered that the majority of black-white people surveyed labeled themselves as multiracial. This can be seen in the tremendous growth of black-white biracials identifying as multiracial since the 2000 U.S. Census first allowed Americans to do so. Recent reports from the census now show that the black-white biracial population has tripled in those 15 years, now leading in the United States as the largest multiple race population.

RELATED: Living Color: Fathers Talk to Their Bi-Racial Sons

“Because people in this group have so strongly been expected to identify as black, they are choosing to assert a new identity, one that incorporates both their black and white heritages," Davenport said. “The ‘one-drop rule’ has been so strong for this population that they feel like historically they have been given less of an ability to choose their race."

Still, although black-white racials proved most likely to identify as multiracial than Asian-white and Latino-white biracials, they were the least likely of the three groups to identify solely as white. Davenport reasons the fact that “black-white biracials are the least likely to adopt a singular white identification is to be expected, given the legacy of hypodescent, historical norms against ‘passing’ as white, and the greater tendency for black-white biracials to be categorized as non-white by other groups.”