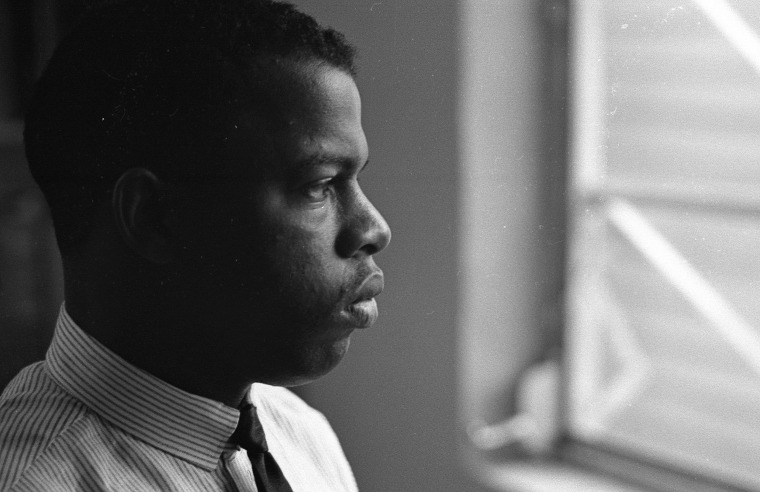

The body of Rep. John Lewis, the son of sharecroppers raised in the Alabama woods, crossed the infamous bridge in Selma on Sunday morning, where Lewis became a wounded but more determined warrior in the fight for racial equity decades ago.

Lewis, often called the "conscience of Congress," died earlier this month at the age of 80, from pancreatic cancer. The procession over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, accompanied by a military honor guard, is one of several events marking the congressman’s death, including two days lying in state in the U.S. Capitol, adding him to the list of just 32 American figures to ever do so.

In every way that America seems capable of today, Lewis is a most honored man. Political allies and absolute foes have described him in laudatory terms (even while, in some cases, attaching the wrong man’s photo). Discussions have turned to renaming the bridge for Lewis instead of its current namesake, an Alabama senator and Ku Klux Klan leader. The Selma expanse is where Lewis once believed he would be killed at 25, as he led protesters who marched for the right to vote only to be met by police officers who brutally attacked the protesters.

But, unlike like the days and weeks after the bloody attack in March 1965, or the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, there has been no bipartisan talk of honoring Lewis, a congressman who died in his 17th term, by passing actual laws.

“He was one of a shrinking crew of people who were essential to the civil rights struggles of the 1960s and after,” said Graham Dodds, an American-born political scientist who teaches about American politics at Concordia University in Montreal.

“If you wanted to be cynical, you would say, had it not been for the death of George Floyd,” Dodds continued, “Congressman Lewis’ death would not have been so publicly marked. But, I also think that the tradition of saying nice things about the dead has something to do with what’s happening here. What I don’t see, what may also be telling, is his death changing any minds. I don’t think the folks who opposed what he stood for are about to embrace voting rights for all now.”

Lewis’ sense that activism and action was essential began as a teenager who, from his home near Troy, Alabama, watched the young preacher from Georgia leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott just 50 miles away. Soon, Lewis was patterning his life after King, deciding he would be a preacher.

Lewis’ first sermon, delivered days after his 16th birthday, landed him in the “Negro section” of the local newspaper. His subject: the biblical figure Hannah’s promise to God that if she were blessed with one child despite her advanced age, she would raise him to be a man of moral courage.

Lewis wanted to go to college, a bold ambition in a state where no public university had admitted a black student. He eventually attended a tuition-free seminary for black students financed by the then-pro-slavery, pro-segregation Southern Baptist Convention and Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. By that summer, Lewis was in Montgomery meeting King.

“I kept telling myself to be calm, that fate was moving now ... but I was still nervous.” Lewis wrote in his 1999 memoir, “Walking With the Wind.” “I had only just turned 18 ... and now I had an appointment with destiny.”

Back in Nashville, Lewis met James Lawson, a King associate, Black Korean War conscientious objector and former missionary in India. In a Nashville church basement, Lawson introduced Lewis and other students to the work of the essayist Henry David Thoreau, theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and ancient Chinese philosophers Mo Ti and Lao Tzu.

Then, he learned Mahatma Gandhi's principles of nonviolence and the idea of “redemptive suffering.” This was about creating something for God’s children on Earth, Lewis wrote in his memoir. Under Lawson’s tutelage, Lewis would go on to help integrate Nashville lunch counters and interstate bus travel as a Freedom Rider.

At age 23, Lewis was the youngest person slated to speak at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He arrived with a draft speech promising that activists “will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did,” according to Esquire magazine. “We shall pursue our own scorched-earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently.” Older activists convinced Lewis to tone it down.

Two years later, in Selma, on that bridge, Alabama state troopers brutally beat Lewis and other protesters engaged in a struggle for the right to vote. They fractured Lewis’ skull. The brutality of the news footage — broadcast during prime-time hours — prompted increased pressure on Congress to pass the 1965 Voting Rights Act, to bar states from enforcing discriminatory laws that had long hindered prospective Black voters.

“He was a true veteran of the civil rights struggle,” said Dodds, who studies American political rhetoric. “That’s why, in my mind, it’s easy to say something nice about Congressman Lewis, far easier than it is to issue a public mea culpa or legislatively change course.”