Acclaimed writer, director and filmmaker Ava DuVernay is a woman on a mission. And as the director of the Oscar nominated “Selma” tells it, the mission is simple. She wants to keep telling authentic stories that matter and to continue creating space for a wider spectrum of voices to be heard in Hollywood.

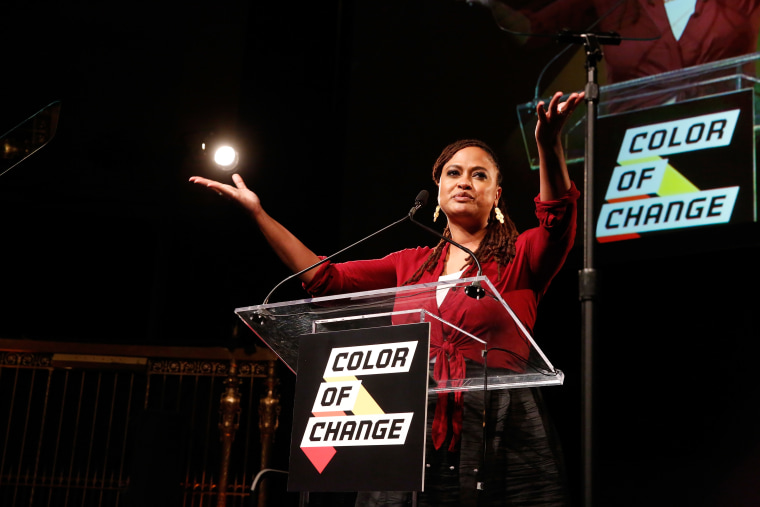

In an extended conversation with msnbc’s Trymaine Lee in New York City on Monday night, DuVernay, following her acceptance of an award during the 10th Anniversary gala for the African American advocacy group ColorofChange.org, the award-winner talked about the impact of the post-Ferguson social justice movement on the arts and fighting to be heard in white male dominated Hollywood.

Trymaine Lee: We’re in this moment where there is so much social activism going on, so many fraught conversations and so many young people actively engaged. Have you been able to translate what’s happing in your art? And has Hollywood in general been able to do that?

Ava DuVernay: Artists reflect what’s happening in the world, so it remains to be seen what art comes out of this cultural moment. I think you are seeing it manifesting in music because music is more of an immediate medium. But film is a long-tailed kind of thing. It takes a while to get a film up and running. Anyone who was writing last summer, this summer, if they are lucky and they are one of the very few who makes their own film or is financed by someone, that work won’t come out until later next year. So, it remains to be seen what this cultured moment— what impact it’ll have on artist in the film space. But I’m wildly interested in figuring it out what it looks like.

I know it’s affecting my work. Michael Brown was murdered while I was in the editing room for “Selma”, so watching you and watching all the coverage in Ferguson influenced the way I was cutting – the way I cut Bloody Sunday, the way I cut [the Jimmy Lee Jackson scene]. So it did effect the post production of it. But could you imagine if I was writing during that time? Someone was. Someone was writing. Someone was shooting something, so it remains to be seen. That’s exciting.

So, it’s a question mark. It’s something that I hope people like you and historians will track, to see the incubation period, the pregnancy, these ideas and what it birthed.

Do you find in Hollywood that there are people who are actively putting up locks around you?

Sure, that’s all Hollywood is, is locks. A whole bunch of closed doors. Any film that you see that has any progressive spirits that is made by any people of color or a woman is a triumph, in and of itself. Whether you agree with it or not. Something that comes with some point of view and some personal prospective from a woman or a person of color, is a unicorn. Because truly the numbers that were just announced by [the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism] are dismal when it comes to women filmmakers, even worse, horrible, horrific when it comes to women of color filmmakers.

When you just imagine that there’s one type of voice that’s really being pushed to the forefront is the white male voice. In terms of cinema, it’s really clear that the rest of us are locked out. So it becomes imperative that people—audiences that want to see that, fight for it, push for it. Support it when it comes, but also artists just become really vocal. So, yeah, it’s a whole bunch of locked doors.

You’ve done a great job of breaking through. But does it ever get too heavy, do you ever get weary of the fight or tired of vocalizing diversity in Hollywood?

Yeah, all the time. One of the reasons why I created the podcast called the “The Call-In” that we do through Array, because as a black artist, every time I sit down with mainstream media I’m asked about issues of race, identity and culture. No one asked what they ask my white male counterparts, which is: ‘Where do you like to put the camera?’ ‘How did you come up with that palette?’ ‘What was your conversation with your cinematographer?’ ‘How did you cast that person?’ I never get asked just film craft questions.

Still at this point in the game where you’ve proven that you’ve got it?

They sit down with me—every time at the “Selma” junket, there was a moment when that was at the forefront, but films before that. Everything I do, it’s always about the skin I’m in. I’m proud of it, it’s fine to do it, but the space that I’ve created so that the people who have the same skin I’m in can talk about what we actually do for a living.

Our art, our artistry, our craft is a space that I had to carve for myself and the same way that I had to carve out Array because I cannot trust that ten years from now I’ll still be the flavor of the month and the studios still want to distribute my films. So I have to create an entity that is constantly growing, so that there’s always place for me to go, for people like me to go. And that’s because I’m very, very sober and clear about where I work. Where I work is in an industry that really has no regard for my voice and the voice of people like me and so, what do I do? Keep knocking on that door or build your own house? So that’s what I focus on.

Among your fellow filmmakers of color and women is there a collective will to say let’s separate, let’s try to do our own thing. Or is it, this is the game and we really have to play it?

It depends. Some people who have reached a certain level of success are happy with what’s going on. Also, some of the filmmakers, black filmmakers did not come up in an independent space like I did. The independent, kind of current, the contemporary black independent film scene is really only maybe 6 years old. So there are some filmmakers who were in the studio system before that who really never experienced film festivals and a whole bunch of indie filmmakers making films with digital cameras and $50,000 you know what I mean? They just don’t know that world.

So I understand and appreciate the disconnect that they have from it. And they’ve attained a certain amount of success, they’ve got a job and it’s okay. They don’t see the urgency. And most of the others who started making films the way that I did, independently, are very focused on the fact—very aware of where we are and how we got here. I’m not sure if everyone is thinking about troubleshooting ways to make our career sustainable, but that’s what I’m focused on.

I intend to be making films until I’m an old lady. So, if God willing I get there, I need to create a paradigm for myself where I can make it regardless of whether or not they still like what I’m making. With the track I’m on, I’m probably going to make something really, really soon that they’re going to hate. Many hated “Selma”. Just because my voice and the voice of the people I come from is antithetical to so much of what Hollywood produces. I don’t think what I’m saying is in particular radical or anything, it’s just different from what they want to sell.

At some point that intersection is going to be a collision that’s not going to make for a healthy relationship. And then what do I do? Nothing? Well that’s not acceptable. I need to keep working. So I need to have a way to work and that’s what Array is and that’s a lot of work I do around Image activism is.

What have you learned most about yourself in this space of growth and evolution and success and learning the industry?

I think so. I think about that a lot and I think I have to stop to see, and I haven’t stopped. One of the things that I was reading earlier about Grace Lee Boggs, she talked about an activism—“A part of activism that’s often overlooked is reflection,” because you’re just on the ground and you’ve got your tactics and you’re working and you’re working and you’re not stopping to journal, to think, to meditate! I don’t think most black people do that enough anyway, but certainly within the activist movement, that’s something she talked about— consciousness and self-consciousness. And certainly for me, I’ll speak for myself, I have not taken enough time to do that so it’s hard for me to answer the question. But I know I’m struggling to stay focused and to stay mindful and not be kind of moved off my course by whatever is going on right now.

And my course is really simple: I want to make films whenever I want to. It’s really easy. I just want to continue to tell stories and I want to help other people tell their stories. It’s not, ‘I want to win this award.’ It’s not, ‘I want this certain amount of money.’ It’s not ‘I want to work with this actor.’ A lot of times, people say, ‘What’s your dream film to make?’ I don’t have one. I just want to make films all the time whenever I want. I’m just trying to keep my job. You know what I mean? And that in and of itself is a struggle because there’s no easy place for us.