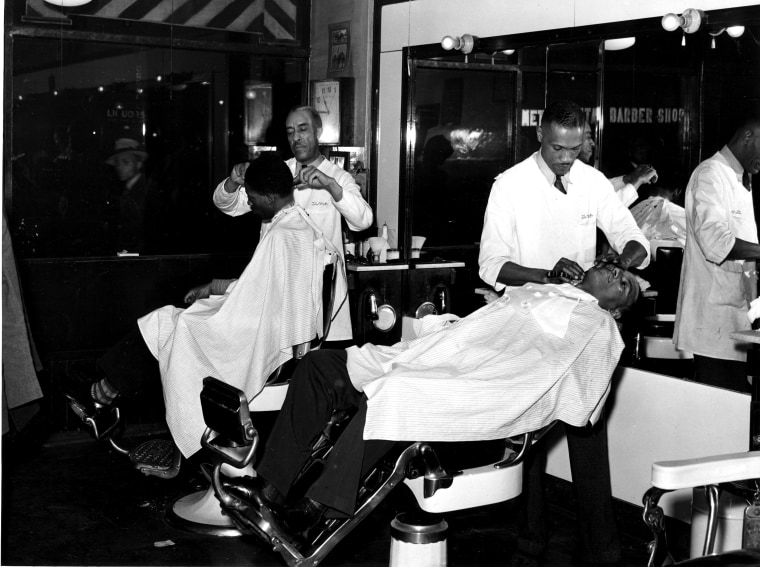

For black men, the barbershop is more than just a place where we get our hair cut.

Before the end of slavery, black barbers spent their days cutting the hair of wealthy white clients, while black men got their haircuts on front porches, in yards, or after hours when white men weren’t around. When slavery was abolished, we were able to officially patronize these businesses as they became locations for community gatherings as well as grooming centers.

Over time these black-owned barbershops became our safe havens, spaces where we can let our guards down to commune with one another without worry of being misjudged, mistreated, harassed, profiled, or shot by police.

Black barbershops have served as our version of country clubs for decades, where we swap stories and talk about politics, race, life, religion, and life. You can walk into any city and find a shop with the latest music serenading your ears, a bootleg movie playing on a rickety television, or meet someone with whom to discuss current events.

Our barbershops house a diverse cross section of the black male experience. No matter where you come from or where you’ve been, every black man who needs a trim, shape up, or a fade can enter these establishments and feel comfortable. Or at least they should.

I recently moved back to Atlanta from Philadelphia, and after searching online for a highly recommended black barbershop in my neighborhood with little success, I decided to just drive and see if I could haphazardly stumble upon a good barber.

Mounds of judgmental rhetoric from the mouths of these brothers began accumulating on the floor like the hairs from my head.

The storefront business with the red and white striped barber’s pole caught my eye, sandwiched between an insurance office and a Caribbean restaurant in a rundown strip mall. It had been two weeks since my last cut. This shop looked as good as any, so I entered.

There were only four brothers inside, one cutting another’s hair in the chair, one in the other chair immersed in his smartphone, and the other standing in the waiting area. The latter brother, modestly dressed in a t-shirt, jeans, and baseball cap, turned toward me when I entered. He motioned to me before I could sit down.

“You need a cut?”

“Yeah man I do,” I replied.

He yanked the barber’s cloth off the armrest, whipping residual hair in the air with a couple of crisp pops.

“My name’s David” I said, extending my hand.

RELATED: What's Inside Her Never Dies' Exhibit Balances Black Beauty and Strength

“Jackson” he responded, meeting my grip with a firm handshake that avoided all the brotherman-pound-grasp theatrics that we sometimes do to prove our blackness. I settled in the chair while Jackson draped the jet black cloth over me and secured the neck strip in place.

“How you want it?” he inquired, swirling me around to face the mirror.

“Skin fade,” I answered, showing him a phone pic of how my previous barber cut my hair. As the buzzing clippers provided the soundtrack, Jackson and I got to know one another. He told me he was from Cleveland and that he had come to Atlanta because of his wife and kids, and for warmer weather.

I told him I was a physician, which sparked an immediate solicitation of treatment options for his current toothache. After waxing poetic about the benefits of ibuprofen, I quickly changed the subject, not wanting my first haircut with him to morph into a clinical encounter.

“Can you believe that cop got off for killing Tamir Rice?” I asked, noting his Cleveland roots.

“Cops are always getting off. It’s open season on black boys in this country,” he said calmly.

Suddenly, Smartphone Brother stood up, pacing back and forth, bemoaning the judicial double standard when it comes to police officers gunning down black men. The other barber argued that there are good and bad cops, and that they have a very difficult and dangerous job. “So if they can’t handle the difficulty and danger of being a cop, find another profession,” Jackson flatly countered.

Just then, a father entered with his young son and approached Jackson.

“I’m going to leave my son here a moment. I have to pay my phone bill next door.”

“I got him next,” Jackson assured him, joking “pay mine while you’re there.”

The man laughed and exited. Smartphone Brother wasn’t done as he continued pacing.

“The world is crazy man. Did you see Will Smith’s son being the model for some Louis Vuitton women’s clothing line?”

“Yeah, like that Bruce Jenner thing, saying he’s the ‘new normal’.” Jackson quipped.

And with that statement, the conversation had turned from police brutality to transgender issues with a transition as awkward as a baby fawn’s first steps. In my surprise, I didn’t notice a middle-aged brother had arrived and was now sharing his own thoughts on Caitlyn Jenner. “Yeah he still a man ‘til he gets his balls cut off.”

“I don’t care what you do in private, just don’t shove it in our faces!” He exclaimed.

I was now facing a dilemma that many Black same-gender loving men face at barbershops when communal discussions on race give way to prejudicial and intolerant statements about sexual orientation and gender identity. Do we speak up? Do we sit back and listen, hoping no one will clock us? Or do we subtly suggest a contrary reality as food for thought?

My heart started racing as Jackson continued cutting my hair, while mounds of judgmental rhetoric from the mouths of these brothers began accumulating on the floor like the hairs from my head.

“They’re sick”

“It’s wrong”

“Disgusting”

I listened until I couldn’t anymore. I had to say something.

“The correct term is ‘transgender,’ and it’s not an illness or a disease,” I stated. “It’s just who people are and how they are wired. I have transgender friends and patients who take hormones to help them physically feel more in line with the gender they feel inside. They’re much happier when their physical appearance matches how they feel. It doesn’t matter if they have their balls cut off or not.”

Time stopped. Some of the men couldn’t look me in my eyes while I spoke. Others glared at me like I had two heads. Even Jackson’s clippers, close to my ear went on pause. Smartphone Brother wasn’t buying it.

“I don’t care what you do in private, just don’t shove it in our faces!” He exclaimed.

“Don’t you think someone who is transgender or gay gets sick of straight people shoving their sexuality in their faces?” I asked.

“We don’t do that!” he retorted.

“Think about it. Everything is geared towards straight people in this country," I started. "It’s like white privilege. White men don’t have to worry about cops killing them like we do. They take that for granted. Heterosexuals talk freely about their girlfriends and wives, engage in public displays of affection anywhere they please, flaunt their sexual proclivities all over social media, and parade pictures of their kids in front of everyone. Gay and transgender people risk being ridiculed, beat, or even killed if they do the same. Straight people take that for granted. That’s privilege.”

RELATED: Diversity and Dolls: How One Parent is Teaching about Race

Middle-aged Brother decided to jump back in. “But this gay marriage thing? Two men or two women raising kids and teaching them to be gay? Kids are gonna be influenced by that sh**.”

“Using that logic, then there should be no gay people,” I responded, “because if everyone is born to straight parents, and they influence kids’ sexuality, then nobody would be gay. Right?”

Silence.

Smartphone Brother stood right in front of me, eyes fixed and inquisitive. “Lemme ask you this… do you think folks are born gay? I mean, usually I know people get introduced to the gay lifestyle when they get molested or something.”

This was the moment of truth. Speaking as a doctor or a concerned outside observer playing devil’s advocate wasn’t going to be enough.

“Look, I’m not straight, and I was never molested or abused as a kid. I’ve just always known I was attracted to men. I was born this way.”

Smartphone Brother nodded. Middle-aged Brother looked at me with a sense of understanding. “Man I had a cousin who was real depressed and always got bad grades during high school. As soon as he came out in college - magna cum laude.” I smiled. He was getting there.

Jackson swung my chair around to face him, seemingly eager to shift the conversation to lighter fare as he gently placed the clippers to my forehead.

“Ok… so just gonna line up the front and we’ll get you moving.”

...The conversation had turned from police brutality to transgender issues with a transition as awkward as a baby fawn’s first steps.

He handed me the mirror after a quick alcohol wipe and spray of sheen. “Looks great” I said, admiring his tapered artistry on my scalp. He removed the cloth and walked to the waiting area to let the young boy know it was his turn. I rose from the chair as he turned back to me.

“How much do I owe you?” I asked.

“Fifteen. Here’s my card. Download our app. You can schedule on your phone next time you wanna see me.”

I gave Jackson a twenty and shook his hand. Smartphone Brother and Middle-aged Brother were now in the waiting area discussing how women become lesbians because they think its “cool,” so I sat with them to suggest alternative theories. In the corner of my eye, I saw Jackson whisper something to the other barber who had been conspicuously silent during the entire exchange. They laughed. I wasn’t sure what was said, but I didn’t really care. As I prepared to leave, I reached out to Smartphone Brother and Middle-aged Brother to shake their hands. They didn’t hesitate.

“Nice to meet you brother” they exclaimed simultaneously.

“Nice to meet you too,” I replied. “Thanks again for the cut Jackson!”

Jackson waved as he flipped his clippers on again and went back to work.

I walked out of the barbershop to greet the brisk January air, wondering how the discussion would continue once I left. That really didn’t matter anymore. I had found my new barber, and next time I’m gonna break down the difference between gender identity and sexual orientation. This was a good start.