Ashley James always had a tendency to question dominant historical narratives.

Last year, she earned her doctorate from Yale University in English literature and two other fields — African American studies and gender studies — that regularly interrogate the versions of history that have been handed down by mostly white men.

“What is shared amongst those fields is this understanding that whiteness and power kind of undergird everything,” James, an associate curator of contemporary art at New York City’s Guggenheim Museum, said.

Now, as the Guggenheim’s first full-time Black curator — a role she assumed in November 2019 — James is translating her academic interests to the institution’s galleries. Her debut exhibition, “Off the Record,” on view through September, features more than two dozen works by 13 contemporary artists — most of whom are Black — that challenge the presumption of objectivity in historical records, journalism and photography.

Their mediums include altered newspapers, photographs, advertisements and government documents that depict history spanning more than a century: 19th century photographs of enslaved Black people are exhibited alongside FBI files on the Black Panther Party from the 1960s, and advertisements from the following two decades that targeted a growing Black middle class.

In shaping “Off the Record,” James particularly relied on the works of Black scholars as sources of inspiration. What she found as a commonality between their works and the museum’s own collection was “a reinterrogation of history.”

“What emerged were artists who really identified the record or document as the material by which they could make the same claim towards revising history, reimagining history, refusing history,” she said.

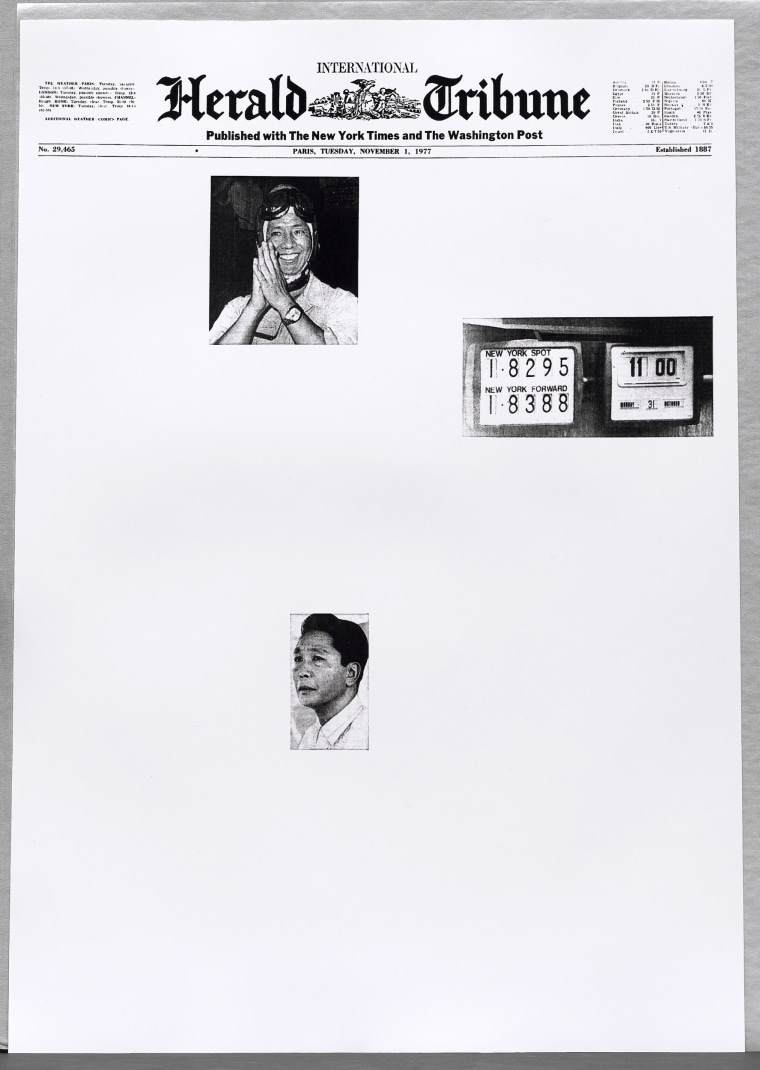

Some of the featured artists removed certain elements of records and media to show the biases lurking beneath them. For her prints “Herald Tribune: November 1977,” the late Sarah Charlesworth removed the text from the newspaper’s front pages to leave only the masthead and photographs. What remains showed how war and other geopolitical subjects dominated coverage and how that portrayal of events “prioritizes constructions of violence and white masculinities,” James wrote in the accompanying wall text.

Photography is an important component of the show, given what James calls a “vexed relationship” between the medium and Black subjects — some of whom have historically been photographed without their consent.

The exhibit features first-hand examples of these kinds of exploitative images, through two 1850s daguerreotypes — the first publicly available forms of photography — of enslaved Africans, from Carrie Mae Weems’ 1995-96 series “From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried.” The images, commissioned by the Swiss naturalist and Harvard University professor Louis Agassiz, were used in attempts to justify racist theories of Black peoples’ so-called inferiority; Weems enlarged, cropped and captioned them to highlight “the lie of the objective photograph,” James wrote.

“It sets up the historical precedent for … understanding that Black individuals emerged in the photographic record in this very violent way,” she said of Weems’ works.

Other featured artists also used their objects of critique as canvases for alternative representations. One of the most overt examples is found in Sable Elyse Smith’s “Coloring Book” series, for which the interdisciplinary artist enlarged and scribbled over pages of a children’s coloring book focusing on the criminal legal system to highlight how kids learn “the logics of incarceration from a young age,” James said.

“In many ways, that’s one of the more literal possibilities against the margins, where in the refusal of drawing inside the lines she’s literally making a new picture,” she added.

The artist Sadie Barnette took a similar, but more subtle, approach with a reproduction of documents from the FBI file the agency produced on her father, Rodney Barnette — a postal worker and the founder of a California chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1968. She adorned sheets from the 500-page document with neon pink and black spray paint. James sees the work as both a repudiation of the state surveillance of Black people and Barnette’s attempt to connect with her father across time.

“What does it mean that she’s finding connection through this violent history?” she asked.

It’s these tensions — between widely accepted representations and counterrecords that resist them — that intrigue James.

“In the creation of something new, I see a certain kind of possibility,” she said.

That sense of possibility was what drew James to exploring a career in art in graduate school, after she curated an exhibit at the Yale University Art Gallery. She went on to complete a fellowship program at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was later hired as an assistant curator at the Brooklyn Museum, where she was the lead curator of the museum’s presentation of the traveling exhibit “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.” She also curated and co-curated, respectively, the museum’s exhibits on the Black artists Eric N. Mack and John Edmonds, the latter of which is on view through August.

That body of work brought her to the Guggenheim, which faced accusations of racial inequality within its ranks in 2019 and 2020. In response, museum leaders approved an expansive two-year diversity initiative last summer. James pitched “Off the Record” shortly after her arrival in 2019, and before the museum’s curatorial staff outlined their complaints about its culture last year, she said.

Working on the exhibitions made clear to James that her ambitions lay in curatorial work, rather than academia: in the former, she could work on a few exhibits per year, whereas in the latter, it might take a few years to have a single paper published, she said.

“That kind of shorter-term realization of projects is something that I really like, as someone who gets a bit bored easily and just wants to see things come to the world more frequently than the pace of academia allows,” she said.

“Off the Record” is, indeed, timely: Last year, Black journalists in particular debated the meaning of objectivity for their field — and how journalists should report on racism — in the wake of George Floyd’s death. But James’ exhibit is also timeless, she insisted, given the ongoing debates — artistic and otherwise — around whether objectivity is ever really possible in a world rife with inequities.

“This show is the same show that I would have done a year ago, two years ago, because what guides my practice and will continue to, I think, is bridging this kind of gap between contemporary art and the large questions that govern our contemporary world.”