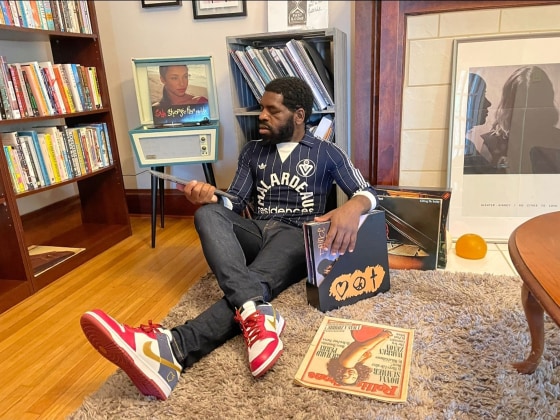

“I want music listening to be a communal experience,” declares poet, cultural critic and author Hanif Abdurraqib.

Abdurraqib is a New York Times bestselling author, having penned five books, including poetry collections, essays and nonfiction, along with articles in several publications. He received a “genius grant” last year from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, he is the writer-in-residence at Butler University and an editor-at-large at the publisher Tin House, and his 2021 book, “A Little Devil in America,” was a National Book Award finalist.

Still, at his core, Abdurraqib simply wants everyone to be as excited about music as he is. He has spent years highlighting “undercelebrated” Black music, like Alabama Shakes’ powerhouse vocalist, Brittany Howard, and the rapper, artist and poet Mykki Blanco. He’s able to share this love of music in his weekly Sonos Radio podcast “Object of Sound” and a live curated concert series at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, or BAM.

“I’m drawn to music that excites and disrupts my comfort. So I’m just always in tune to what broadens my musical palette,” Abdurraqib said. “I spend a lot of time doing a lot of writing and collaboration with folks who are younger than me. And I’m always asking what they’re listening to, and I keep my ear to music coming out of places beyond America.”

“Object of Sound” is a playground for Abdurraqib to explore how music shapes culture in impassioned conversations with artists like H.E.R., Ibeyi, and Meshell Ndegeocello. In the third season, he’ll look at the history of Detroit techno, explore the link between pop music and sports stadium chants and talk about great movie soundtracks with New York Times critic-at-large Wesley Morris. And every episode includes a carefully curated playlist from Abdurraqib.

“There are folks who I’m a fan of and I talk about the history of their life and career with,” he said. “Then there’s folks where it’s like, ‘Gosh! Your music invites me in! It’s so generous,’ and I want to extend that generosity through conversation.”

Abdurraqib is a master at bringing seemingly disparate figures together in accessible and beautiful ways through his writing and curating. The live concert series is perhaps the perfect example of that — a coming performance blends the British rapper Little Simz with the legendary poet-activist Nikki Giovanni. He has tapped artists from different generations, sometimes even introducing the musicians to one another for the first time. Hosting Ghanaian American singer-songwriter Moses Sumney and Danity Kane member-turned-indie favorite Dawn Richard to gospel legend Mavis Staples and singer-songwriter Amy Helm, Abdurraqib has said organizing such a music series is like “living a dream.”

Abdurraqib has been to very few live shows in recent years because of the coronavirus pandemic. So he admits he was tentative about the concert series. But that has eased since the festival kicked off last month.

“I’ve spent so much of my life going to live shows. … I think I became more interested less in quantity and more a pursuit of the spectacular,” he said. “That also formed my curation with BAM, that never-ending pursuit of the spectacular. Now I find myself even still being tentative about going to live shows — until I’m there. I’m immersed in something special, and I don’t want to trade this at all.”

Over the years, Abdurraqib has managed to establish himself as a vital music critic and writer. It is just as much his lyrical reflections on Fall Out Boy and Migos as his accessible writing style that defines his artistry. “I don’t think of myself as an expert, as someone on high, dictating to an audience. I believe that most of my writing is seeking a conversation partner,” Abdurraqib said.

The Los Angeles Times has hailed Abdurraqib — who said he doesn’t even like to read articles about himself — as the “literary heir to Greg Tate,” who died in December. Although it’s a flattering and “kind sentiment,” Abdurraqib said, “I don’t think we need a new Greg Tate. I think Greg Tate was and is singular.”

“Greg Tate’s work meant a lot to me, and I don’t think I’m in any position to be anyone but myself. But that self is formed with the great many tools that Greg Tate allowed for me to witness and be witness to,” he said.

“If I get to be a small part of the legacy that he built, just by being someone who uplifts his work and who has a deep love for his work and who, through that deep love, gets to participate in the act of criticism … that is more than enough for me.”