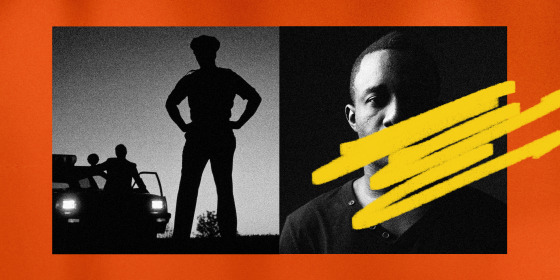

Michelle Kenney still has nights when she stays up crying over the death of her son, Antwon Rose II, a 17-year-old high school student who was shot three years ago by an East Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, police officer.

Time has also not healed the pain Zion Carr grapples with after witnessing the shooting death of his aunt, Atatiana Jefferson, by a Fort Worth, Texas, police officer in 2019.

And it has not lifted the weight Darnella Frazier still carries after she filmed a video last year of former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd's neck, killing him.

For victims' relatives, witnesses and those who are subjected to replays of videos of police brutality against Black people, there's no such thing as getting over the trauma it causes, according to experts.

William A. Smith, a professor of ethnic studies and chair of the education, culture and society department at the University of Utah, has done extensive research on how trauma affects marginalized groups, especially Black people. He’s coined the term “racial battle fatigue” to describe how continued acts of aggression or discrimination can lead to anxiety, stress and even health issues.

“It’s a systemic race-related repetitive stress injury,” Smith said. “It’s not a post-traumatic stress disorder or injury because we’re not in a post-racist society. It’s something we have to deal with every day.”

Trauma "doesn’t leave you," said Rufus Tony Spann, a licensed professional counselor and a Forbes health adviser.

"So a lot of times we may say PTSD thinking that it’s post-trauma, but for many people, it could be continuous trauma," he said. "And a continuous trauma is that I experienced an actual event that either has shocked me, it has changed my thought process or instilled fear in me."

That fear is what prompted Zion's mother, Amber Carr, to file a federal lawsuit in September, saying the now 9-year-old suffers from "anxiety, terror and agony" from witnessing Jefferson's death.

'Extreme mental and emotional distress'

Zion was playing video games with Jefferson, 28, when a neighbor called police for a welfare check because the home's front door was open. According to the suit, the door had been left open to allow a cool breeze to blow inside.

Former Fort Worth Police Officer Aaron Dean responded to the call just before 2:30 a.m. on Oct. 12, 2019, and walked into the backyard of the home. When Jefferson heard a noise outside, she grabbed her legally owned gun for protection and went over to a window to investigate, the lawsuit said. Dean, who was standing outside the window with a flashlight, shot and killed Jefferson.

“At the age of 8, Z.C. was forced to watch the murder of his aunt, Atatiana Jefferson, at the hands of Fort Worth Police,” the lawsuit stated. Zion has now been left with "severe and extreme mental and emotional distress," it said.

Carr was not available for an interview. The family said in the suit that the city is responsible for Zion's trauma. It names Dean, Police Chief Ed Kraus, the city of Fort Worth and former Mayor Betsy Price as defendants.

Kraus, an attorney for the city and a representative for Price did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the lawsuit. A lawyer for Dean said he could not comment because of a court-issued gag order.

Dean was arrested shortly after Jefferson’s death and charged with murder. The trial for the former officer, who has been out of jail on bail, will start no earlier than late November, according to officials.

'I'm not who I used to be'

On the one-year anniversary of Floyd's death, Frazier described how being a witness to the killing changed how she viewed life and took away part of her childhood.

"I am 18 now and I still hold the weight and trauma of what I witnessed a year ago. It’s a little easier now, but I’m not who I used to be," she wrote in an emotional Facebook post on May 25. "I used to shake so bad at night my mom had to rock me to sleep. … Having panic and anxiety attacks every time I seen a police car, not knowing who to trust because a lot of people are evil with bad intentions. I hold that weight."

Frazier was walking to a corner store with her 9-year-old cousin when police attempted to arrest Floyd after receiving a call about a counterfeit bill. Frazier said she happened to be "in the right place at the right time" when she captured footage of his arrest. The video would later play a key role in Chauvin's conviction.

Frazier, via her representative, declined to be interviewed.

In the Facebook post, she acknowledged the impact her video has had but wrote that she's still "trying to heal from something I am reminded of every day."

'I have to figure out ... how to survive'

Kenney said she has days when the weight of Rose's death is so paralyzing, "I can’t get off my couch; I can’t stop crying." Her son was fatally shot on June 19, 2018, by former East Pittsburgh Police Officer Michael Rosfeld after a traffic stop.

Rose had fled from a vehicle that was involved in a drive-by shooting earlier that evening. The teen had been sitting in the front passenger seat of an unlicensed taxi when a person in the back seat shot at two men in North Braddock, Pennsylvania.

Rosfeld fired at Rose as he fled, hitting him three times. Video of the incident captured by a bystander and posted online triggered a series of protests in the Pittsburgh area that included a late-night march that shut down a major highway. The former officer was charged with homicide and later acquitted.

"How do you take your mind off of a video that was circulated worldwide of your son being gunned down?" Kenney said. "Everyone thinks that is just a situation where you have to figure out the process of grief. No, I have to figure out day to day how to survive."

Therapy and talking with a pastor have been some of the ways Kenney has been able to keep going, but she said more needs to be done on the local level to assist families affected by police violence.

"I wish that every city had a resource agency where these families could go to get everything they needed, whether it was legal advice or mental health advice," she said.

'Black mental health matters'

A 2018 study found that Black people experienced days of poor mental health over a three-month period after a police killing of an unarmed Black person in their state. Law enforcement kill more than 300 Black Americans, at least a quarter of them unarmed, each year, according to the study.

These killings have "adverse effects on mental health among Black American adults in the general population," the study said. "Programs should be implemented to decrease the frequency of police killings and to mitigate adverse mental health effects within communities when such killings do occur."

Following Floyd's death last year, officials in Newark, New Jersey, diverted 5 percent — nearly $12 million — of the city's Public Safety Department budget to create the Office of Violence Prevention and Trauma Recovery.

The office has combined several community-based units under one umbrella to provide resources faster in the wake of a violent event.

“It’s taking a public health approach to violence,” said Juan Rios, an assistant professor who directs the master of social work program at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. “So if there’s a shooting, we’re able to not just work with the victim, but also work with those in the community who may be affected.”

Rios, who works with the trauma recovery office, said they can set up community members with therapists, provide mental health resources and even assist with possible relocation costs.

"This is innovative," Rios said. "What we're saying is that safety and well-being is not just in the hands of law enforcement; it's also in the hands of folks who are adequately trained to put people first and take a humanistic approach to addressing the whole person."

On the national level, organizations such as the Black Mental Health Coalition, the Association of Black Psychologists and the NAACP provide support, Rufus Tony Spann, the Forbes health adviser, said.

Spann has also started working with a new tech company called Hurdle, which was formed in response to the killings of Black men by law enforcement and provides mental health resources to those in need.

Prominent civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump often deals with grief-stricken loved ones and community members after a police killing. He has represented the families of Floyd, Daunte Wright, Breonna Taylor and many others. The lawyer has established relationships with mental health organizations around the country that he can refer clients to, he said.

“We have to continue to talk about the mental effects on Black people because oftentimes society chooses to disregard it,” Crump said. “It’s almost as if we have to say Black lives matter, but Black mental health matters, as well.”