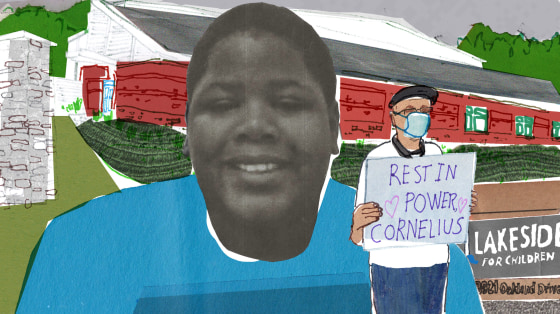

During lunch on April 29, Cornelius Frederick threw a sandwich at another boy in the Lakeside Academy cafeteria. A staff member responded by tackling Cornelius to the ground, and then, for 12 minutes, as Cornelius struggled and gradually grew still, seven men who worked for Lakeside held him down, some putting their weight on his legs and torso.

Cornelius, 16, had been placed at Lakeside, a facility for at-risk youth in Kalamazoo, Michigan, six months earlier as a ward of the state. Lakeside staff members told state investigators they needed to put Cornelius in a restraint to prevent things from escalating; one employee said Cornelius' food throwing could've turned into a riot.

When the staff members let go of Cornelius, his body was limp, surveillance video shows. According to the police report, several employees said they thought he was faking, but some also noticed foam at his mouth. Twelve minutes later, they called 911. Cornelius died at the hospital two days later. The medical examiner ruled it a homicide, the result of Cornelius being asphyxiated.

Cornelius' death resulted in criminal charges against three Lakeside employees, a lawsuit by his estate against Lakeside and new emergency rules for youth facilities implemented by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Lakeside was effectively closed in June.

An NBC News investigation found an extensive trail of warnings about staff misconduct at Lakeside long before Cornelius' death, raising questions about why the state didn't take more drastic action until it revoked Lakeside's license last month. Over 2,000 pages of documents obtained by NBC News — including police reports, 911 call logs, financial audits and tax forms, search warrants, state inspections and court filings — detail years of abuse allegations at Lakeside, in addition to a string of violations substantiated by government agencies in Michigan, as well as two other states that sent children to Lakeside.

In the 2½ years before Cornelius died, 56 violations at Lakeside were substantiated by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. They ranged from botched paperwork and facility management's failing to check whether employees were on a state registry of child abusers to improper restraints and staff members' being "overly aggressive" with youths.

Emergency services were called to Lakeside 237 times in the 18 months before Cornelius' death, including 12 times for reports of assault, eight times for sexual assault allegations and four times for possible child abuse. Nine days before the fatal restraint of Cornelius, another boy ran away from the facility and pleaded with police not to take him back because he feared for his safety.

"They had done this before — this was not a one-off," said Geoffrey Fieger, an attorney for Cornelius' extended family, who is suing Lakeside and Sequel. "This was not a random or unexpected occurrence. This was a practiced pattern by Lakeside."

NBC News' findings also raise questions about Sequel Youth and Family Services, the Alabama-based for-profit company that ran Lakeside. Sequel said in April that it serves 10,000 children annually across 21 states, including foster children and children with complex behavioral and mental health needs, reporting more than $200 million in revenue in 2016. A previous NBC News investigation in March 2019 found that staff members at another Sequel-run facility, in Iowa, improperly used restraints, resulting in injuries such as loss of consciousness and broken bones. The company pledged to adopt a behavior management program that would minimize the use of restraints on children at its facilities.

Despite the pledge, multiple state agencies and advocates have since found that the improper use of restraints on children in Sequel's care has continued, not only at Lakeside, but also at other facilities across the country.

"The list of violations shows it," said Jason Smith, a policy expert at the nonprofit Michigan Center for Youth Justice. "This was a larger issue. It was systemic. It was cultural. It was really the fault of Sequel Youth and Family Services."

Do you have a story to share about facilities for at-risk youth? Contact us.

Michigan's Department of Health and Human Services acknowledged shortcomings in its oversight of Lakeside and Sequel, saying the state needs to do a better job of protecting the children in its care. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, ordered the department to ensure that Sequel no longer does business with child care facilities in the state.

Lakeside, a nonprofit established a century ago, declined to answer questions but said in a statement, “We continue to extend our deepest sympathies to Cornelius’ family.”

Sequel declined to make anyone available for an interview and instead released a statement in response to questions. The statement said that the restraint used on Cornelius violated Sequel's policies and training and that the company is implementing a "restraint-free model of care at every Sequel program."

"That work is ongoing and requires extensive time and ongoing training," Sequel said.

'A Sour Patch Kid'

Lakeside was the third facility Cornelius had been placed in since his mother died in her sleep of heart failure several years earlier — Cornelius was the one who found her. His father lost custody after he was incarcerated.

Black children, like Cornelius, are 35 percent more likely than white youths to be placed in group homes or residential treatment facilities. Nationwide, 33 percent of children in foster care are Black, but Black children make up just 15 percent of U.S. children.

At age 12, separated from three siblings, Cornelius landed at Wolverine Human Services, a youth facility in Detroit. Will White, a former peer support specialist at Wolverine, got to know Cornelius in 2017 and 2018. Cornelius, or "Corn," as most people called him, tried to teach White how to play chess, and he loved to show off card tricks. He wanted to become a counselor. He was large; a former resident of Wolverine who recalled meeting him joked that the first thing Cornelius said was "Can I get your snack?"

Cornelius wanted to be liked, White said, even if it meant getting in trouble by stealing a staff member's cellphone so someone else could get on social media.

"Cornelius was a Sour Patch Kid," White said. "He was a kid that had a really tough exterior that could be a little frightening, but he had a really soft heart."

Last fall, Cornelius arrived at Lakeside, which housed up to 124 youths ages 12 to 18. It opened as an orphanage in 1907, and Sequel took over operations in 2006 when the nonprofit facility fell into financial trouble.

Residents recently told state investigators that staff members at Lakeside commonly used restraints. One boy said "staff sometimes hold kids on the neck" to get them to comply, according to a Michigan Department of Health and Human Services report in June. Another resident said he'd been restrained by six staff members at once, the report said, and two others said staff members often used the physical holds on boys who didn't listen to instructions or were "being a dummy."

Sequel's policies dictate that restraints should be used only as an emergency intervention when a child presents a danger to himself or to others.

"Outside of these types of instances, a restraint is not an appropriate first response," Sequel said in a statement. "Restraints are never to be used as a means of coercion, discipline, convenience, or retaliation by staff."

Lakeside staff members placed Cornelius in physical restraints at least 10 times in the six months before he died, according to records obtained by NBC News.

During one such incident in January, five Lakeside employees restrained Cornelius for throwing a football at a peer and trying to push a staff member. The employees took turns lying across his midsection and his legs, according to a state investigation. Lakeside staff members documented that the restraint lasted 10 minutes; however, security video showed that it actually lasted 36 minutes, police records state. Once Lakeside employees let go of him, Cornelius was seen on the video crying and had trouble walking, police said.

"When we saw how inconsistent their written incident reports were with what we saw on the video, it was shocking to us," said David Boysen, assistant chief of Kalamazoo Public Safety, the police force. "When you look back at it, this was a pattern of behavior by some members of the staff there."

Sequel said it fired the staff members involved in the January restraint quickly but didn't give specific dates.

"If they kept restraining kids the way that they did, a child was going to die."

Sara Gelser, Oregon state senator

Spencer Richardson-Moore, who worked at Wolverine when Cornelius was there, said he understands that youths in such facilities can test employees' patience. However, the facilities are supposed to use trauma-informed techniques to calm children down, he said.

"If they are rough around the edges, it's because they've lived a life they didn't ask for," Richardson-Moore said. "Let's be honest: A young Black boy whose father is in prison, his mother dies while he's young, then he has to go into a system and has to figure life out. He didn't have family or siblings around, he has to grow up around a bunch of other kids he don't know and may never see afterward and then gets shifted from one place to another. That's a lot for a kid."

Michigan government missed warning signs

When police returned to campus a few days after Cornelius' death to investigate, an attorney for Lakeside told them that they weren't allowed to interview any current employees, according to a police report.

Sequel's attorneys also instructed Lakeside not to give police the security video that showed staff members restraining Cornelius, Boysen said, but officers had already obtained it.

Sequel said that Cornelius' death was "unconscionable" and that the company was "continuing to work closely with law enforcement and state officials to help ensure justice is served."

Boysen said that Lakeside had "lost all control" over the children in its care but the Kalamazoo police had no authority to close the facility. That authority rested with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, which was well aware of Lakeside's shortcomings, records show.

"Could we have done that better? Absolutely."

JooYeun Chang, Children's Services Agency

In a 2018 investigation, the state found that a Lakeside resident had been subjected to four unwarranted restraints, that one staff member lied to state agents about it and that staff members failed to report that the child had been injured in one of the restraints. State agents also said it was "concerning" that none of the staff members thought that the restraints were inappropriate. Another state investigation last year found that a staff member hit a boy in the face after he used disrespectful language. And an investigation in February found evidence that a staff member choked and punched a child, although the employee denied it.

Each time, the department's investigators said the state didn't need to take away Lakeside's license, as long as the facility submitted an "acceptable corrective action plan."

NBC News obtained 23 of these corrective action plans, dating to the beginning of 2018. Drafted by Lakeside officials, the plans typically detailed that employees would go through more training sessions, and that employees involved in violations had been disciplined or fired. An October 2019 plan noted that a Sequel official would visit campus at least four times a year to "conduct training and audits," and that management at both Lakeside and Sequel would monitor security video for safety violations.

JooYeun Chang, senior deputy director of the department's Children's Services Agency, which oversees facilities like Lakeside, conceded that the state "did miss some of the early warning signs."

While the department monitored facilities to ensure that they complied with corrective action plans, Chang said, state oversight sometimes failed to remedy systemic issues. In a review after Cornelius' death, she said, the agency discovered that 76 of 151 residential children's facilities had either one serious incident in the past two years or repeat incidents related to safety.

"Could we have done that better?" she said. "Absolutely."

The state made several changes last week to the way it oversees facilities like Lakeside, including increasing on-site reviews to four a year from one. The state also banned any restraint that restricts breathing, and it now requires that when a youth is restrained, the facility must notify the child's family within 12 hours and the department within 24 hours.

$12 an hour

Three Lakeside employees have been charged with involuntary manslaughter and child abuse as a result of Cornelius' death: Michael Mosley, who initiated the restraint; Zachary Solis, who laid his body across the boy's torso as supervisors watched; and Heather McLogan, the nurse who called 911. All three are pleading not guilty, and argue that they were following Sequel protocol.

"Nobody said to stop, move down, move up, move out — none of that," said Donald Sappanos, an attorney for Solis. "In fact, afterwards, there was a meeting where all the employees that were involved in the restraint were congratulated and told, 'Great job.'"

Anastase Markou, McLogan’s defense attorney, said his client arrived at a “chaotic scene,” and now “she’s been accused of not doing something based on some form of legal duty which I’m still trying to decide what legal duty she had.”

Kiana Carolyn Garrity, Mosley’s attorney, argued that the restraint was justified because Cornelius was a large teenager, and had been threatening other students earlier that day. Both Garrity and Sappanos said their clients did not lay their body weight on Cornelius, challenging what the prosecutor and the state health department have said.

“Supervisors on scene did not intervene because they did not see anything that was violating their policy,” Garrity said.

"It was a powder keg waiting to happen."

Donald Sappanos, attorney

It's a difficult work environment. According to police records and interviews with two former Lakeside youth counselors, who asked not to be identified to avoid retaliation, some of the facility's residents had hit or thrown things at staff members and frequently ran away. But across its facilities, Sequel relies heavily on young staffers who have limited experience working with children who have complex needs, former staff members at Sequel facilities said.

Lakeside youth counselors started at $12 an hour, former staff members said. Solis received just two hours of classroom training in restraint procedure, Sappanos said.

"I think it was a powder keg waiting to happen," Sappanos said. "And now Sequel's running for the hills."

Sequel said it emphasizes "de-escalation" in its programs. Ten employees were fired as a result of Cornelius' death.

Sequel told NBC News in March 2019 that its uses of restraints "were all appropriate," but by then, the company had been working for a year to adopt a restraint-free behavior management program called Ukeru. The program, grounded in trauma-informed care and conflict resolution, was supposed to minimize the use of restraints, in part by letting youths hit foam pads to exorcise their aggression.

The company operates more than 40 programs nationwide. Sequel implemented Ukeru training at 10 facilities, including Lakeside, as well as a youth facility in Ohio called Sequel Pomegranate Health Services.

Ohio's state government moved last month to close the Pomegranate facility, citing a failure by staff members to use alternatives to restraints, creating an unsafe environment.

There have been problems at other Sequel facilities. Sequel closed Red Rock Canyon School in St. George, Utah, last summer after a riot and multiple allegations of staff members' assaulting students.

Starr Commonwealth, a Sequel-run facility in Albion, Michigan, continued operating in spite of 58 violations substantiated by the state since July 2017. The state found at least four incidents in the past two years in which residents were injured while being restrained, but it didn't touch the facility's license. Starr CEO Elizabeth Carey said this month that the facility would end its contract with Sequel and that it is ending its residential programs.

Sequel said it is “disappointed” that Starr decided to end its relationship with the company. Sequel also said it is reviewing options regarding the Pomegranate facility, and will “continue to make improvements at the program.”

"We have internal quality control and rigorous training to ensure that the care and support we provide our students is consistent with all best practices and reaches our own high standards of respect for our students' dignity," Sequel said in a statement, adding that it installed video cameras on all its campuses to monitor compliance.

Cross-country concerns about Lakeside

Counties from across Michigan sent children to Lakeside, and at the time Cornelius died, at least 30 of his peers had come from as far away as California and Tennessee. Lakeside collected $427 per day per child from Oregon.

Officials from at least three states had raised alarms about the types of restraints used by Lakeside employees.

Records show that the Minnesota Department of Corrections raised concerns in 2018 that Lakeside wasn't using physical restraints correctly. California's Department of Social Services documented at least seven violations in the two years before Cornelius died, including concerns with "types of physical intervention possibly being utilized."

Sara Gelser, an Oregon state senator who has investigated where her state sends foster children, visited Lakeside Academy in January. Oregon had two children at Lakeside when Cornelius died.

"When we were there, they bragged about how their use of restraint was declining and they only used it when there was something serious," Gelser said.

But Gelser had reviewed police reports and state investigations describing inappropriate restraints. She said she told Sequel CEO Chris Roussos during her Lakeside visit that she was concerned that "if they kept restraining kids the way that they did, a child was going to die."

Oregon's Department of Human Services announced this month that the state would no longer send children to Sequel facilities.

After Cornelius' death, California revoked Lakeside's certification and relocated the children who were there. The state has 79 children placed at three other Sequel-owned facilities, all in Iowa.

'They failed'

Residential programs like Lakeside should be an option of last resort, said Chang, of Michigan's Children's Services Agency. Like other states, Michigan has expanded access to family and community-based services for at-risk children, especially for children with mental health issues. But the state needs to do more, she said.

"Until we address how we use these facilities and stop warehousing our kids in an environment where order and control is the most important factor and not meeting their therapeutic needs, there will always be this risk factor," Chang said.

It was shameful, she added, that Cornelius spent so much of his brief life in the system.

"The government does some things really well," she said. "It will never be able to raise a child."

Boysen, of the Kalamazoo police, is glad that Lakeside is closed, but he thinks the state should've taken more decisive action earlier.

"They failed," Boysen said. "It's too bad that, you know, it takes something like this to make a change."