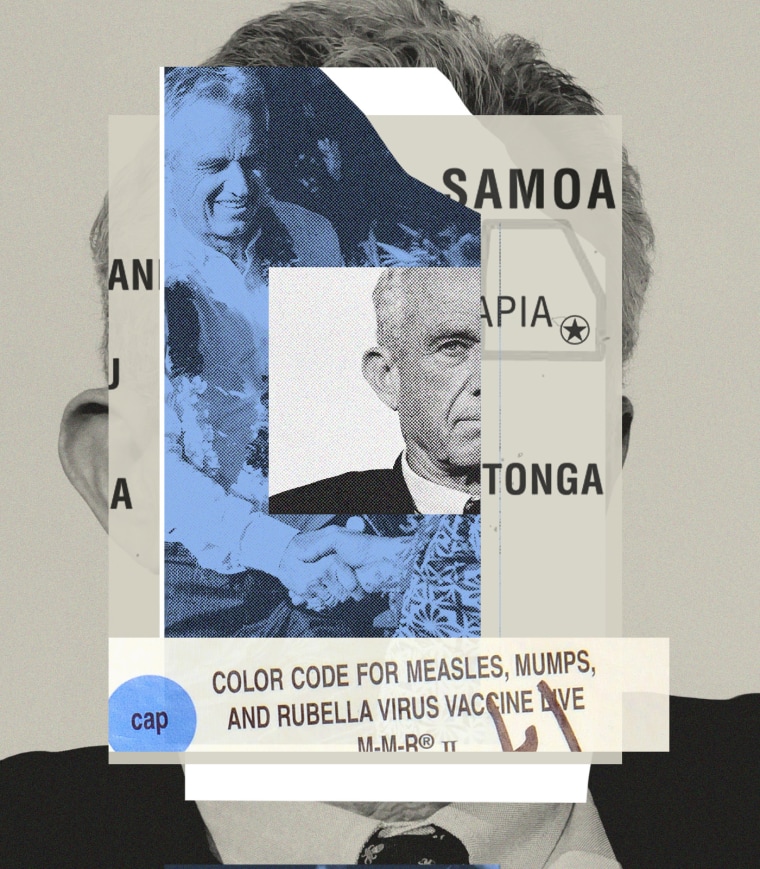

When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. visited in June 2019, Samoa was on the brink of crisis.

The government had suspended measles vaccinations the year before after an improperly prepared vaccine killed two babies. Though the vaccinations resumed months later, many parents weren’t convinced that the shots were safe, leaving thousands of their smallest children unprotected against a highly contagious disease as it was resurging across the globe.

With fewer than a third of Samoa’s babies vaccinated, experts and officials feared for the Pacific Island nation. But Kennedy saw an opportunity.

Kennedy, then chairman of Children’s Health Defense, an anti-vaccine nonprofit, later recounted online that Samoan “government officials, including the Prime Minister were curious to measure health outcomes following the ‘natural experiment’ created by the respite from vaccines.” Wherever the idea originated, Kennedy was quick to offer them a way to do it.

It’s a milder version of an idea he has long championed at home — that the safety of vaccines, well established by scientific consensus, needs to be studied further in the kind of trials that would depend on a large group of children going without them. With a renowned health informatics expert in tow, Kennedy visited Samoa in 2019, to pitch the prime minister and ministry of health on an information system that would track the impact of medical interventions, including vaccines, on the nation’s 200,000 citizens.

Months after Kennedy’s visit, the question of what would happen to Samoa’s unvaccinated babies was answered. A measles outbreak swept the country, sickening thousands and killing 83, mostly small children. As measles raged, Kennedy stayed connected to the island, writing to the prime minister to raise concerns about the vaccine and providing medical guidance to a local anti-vaccine activist who posted false claims about the vaccination campaign and promoted unproven alternative cures.

Kennedy’s time in Samoa and influence there have come under renewed scrutiny since President Donald Trump announced his nomination as secretary of health and human services. In that role, Kennedy would oversee U.S. public health policies and programs, including those related to vaccines, at a time when childhood vaccination rates are dipping and the threat of emerging diseases like bird flu is growing. Kennedy’s spokesperson within the Trump transition team declined to respond to questions about Kennedy’s visit to Samoa.

Kennedy, who did not return requests for comment, has repeatedly denied any responsibility for Samoa’s outbreak and its consequences. “I had nothing to do with people not vaccinating in Samoa,” Kennedy said in 2021 in an interview for the 2023 documentary “Shot in the Arm.” In 2021, he told the Samoa Observer that he and the prime minister had talked “a limited amount” about vaccines during his visit.

He has also questioned whether measles caused the spate of deaths, calling it a “very controversial supposition” in a 2023 interview with NBC News.

To be sure, Kennedy’s role in the crisis is complex, and some details of his trip to Samoa remain unclear. But interviews with government officials, international public health experts and local anti-vaccine activists — along with media reports and reviews of social media posts, blogs and podcasts at the time — show Kennedy and his nonprofit tried to exploit the initial vaccine accident to promote anti-vaccine misinformation that may have cost lives.

“There is abundant evidence that when immunization rates drop low enough for a highly contagious disease like measles, measles will come storming back,” said Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the co-inventor of a rotavirus vaccine. Kennedy’s impulse to stand back and let such a “natural experiment” unfold put children at greater risk, Offit said, adding, “I can’t imagine anything less ethical or more cruel.”

Arthur Caplan, a professor of medical ethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, called the plan to study the results of the vaccination pause “irresponsible at best.”

“You can’t go to a tiny country and say, ‘Oh, well, you’re not giving the measles vaccine. Let’s turn this into a study of whether or not it helps,’” Caplan said. “We know it helps.”

When two babies died within hours of each other on the Samoan island of Savai’i in July 2018, news spread fast.

“Samoa is a small place, so there is no such story that wouldn’t be known in a matter of seconds, in a matter of minutes, everywhere,” said Simona Marinescu, then the United Nations’ resident coordinator in Samoa. “Imagine the shock.”

Samoa’s health care system was already stretched thin. Doctors and nurses, many of whom left for opportunities abroad, were increasingly in short supply and rural areas often went unserved. Lack of access and education coupled with government complacency had driven vaccination rates down over the decade. The July deaths stopped them altogether.

The ministry of health immediately suspended the vaccine program and recalled all measles, mumps and rubella vaccines. Announcing an inquiry into the deaths on Facebook, then Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi expressed sympathy for the grieving parents, suggesting his grandson had also been injured by a vaccine, a detail anti-vaccine groups seized on.

And while Samoans waited for official answers, those activists filled the vacuum. Within a week, Del Bigtree, director of the Texas-based Informed Consent Action Network, a partner group to Kennedy’s nonprofit, had turned the babies’ deaths into social media content. His group created a two-minute video backed by a somber piano track that linked the Samoa tragedy to false claims about the measles vaccines and promoted the Children’s Health Defense film, “Vaxxed.”

“That video is up to 174,000 views and climbing,” Bigtree said on the July 12, 2018, episode of his internet show, The Highwire. “Share it with everyone you know. This is how we are changing the world.”

Kennedy’s Children’s Health Defense posted about the deaths on its Facebook page, too, suggesting they were proof the vaccines were unsafe.

The truth came out, if slowly, and implicated two nurses. According to police, Luse Emo Tauvale didn’t check the label on a vial of expired anesthetic and mistakenly used it to mix a vaccine that she then gave to a 1-year-old girl who died shortly after. When another mother, having seen the reaction, protested against having her son vaccinated, Leutogi Te’o, a nurse manager, convinced her to go ahead. Ignoring other nurses who warned her to make a new vaccine mixture, Te’o administered another shot from the poisonous batch. The second child died as quickly as the first. Both nurses were arrested a month after the deaths. They pleaded guilty to manslaughter and in 2019 were sentenced to five years in prison.

Long after the nurses’ arrests, Kennedy’s Children’s Health Defense continued to publicly question how the babies died. “Vaccine safety science needed,” one post read.

Some 10 months after halting the vaccine program, Samoa started it up again.

“We have to do a lot of catch-up,” Dr. Take Naseri, Samoa’s director general of health, said at the time.

But parents weren’t rushing to get in line. Edwin Tamasese, a sustainable farmer and entrepreneur, emerged as a voice for their skepticism and would come to be known internationally as the face of vaccine resistance in Samoa. Tamasese was generally critical of Western medicine; what the immune system couldn’t manage on its own could be treated with vitamins A and C, and for more serious illnesses, he turned to herbal remedies like papaya leaf extract sourced from his own farm. He shared these thoughts, and others, on Facebook, alongside anti-vaccine content, including articles and videos from Children’s Health Defense on the dangers of vaccines. Tamasese sparred with American users on pro-vaccine pages, but he was far from a major influencer — until the deaths of the two babies.

“Vaccines for my little country have been the subject of a bit of international media lately and because of this I have looked a bit deeper into it,” he posted to one Facebook forum in 2018, along with a photo of his 6-month-old daughter’s vaccination record, empty aside from a Hepatitis B vaccine given at birth that he said he would have liked to prevent. “Are we missing out on opportunities to explore alternative options to vaccines that could be safer and more effective?”

In April the next year, Tamasese participated in a professional exchange program run by the U.S. State Department, and at a government function, met Malielegaoi, then the Samoan prime minister. According to Malielegaoi, who replied to questions over email this month, Tamasese talked to him about Children’s Health Defense and floated the idea that Kennedy could come to Samoa and discuss “the deeper issues on vaccines.” It’s unclear whether or how Tamasese knew Kennedy at the time.

Kennedy accepted the invitation, and on June 1, he and his wife, actor Cheryl Hines, attended an official Independence Day celebration. The rest of Kennedy’s trip was less public. Photos posted to his Instagram account at the time show Kennedy visiting churches, playing on the beach with a group of kids, and catching starfish in the ocean.

According to Naseri, the director general of health, government officials arranged a dinner for Kennedy at a resort. Naseri said that he spoke briefly to Kennedy there and that Kennedy shared his view that vaccines weren’t safe. Naseri said he told Kennedy that vaccines solved most of the country’s infectious disease problems, “and we don’t want to stop that.”

Kennedy wasn’t alone at the dinner. He brought the Children’s Health Defense’s new chief information officer, Dr. Michael Graven, a lauded neonatologist known for creating information systems that tracked and improved health outcomes in the world’s poorest countries.

In 2012, Graven co-wrote a letter arguing for integrated health systems to better assess vaccine impacts, adverse events and safety monitoring.

In 2019, Graven was analyzing the data for a study that would be published in 2020 by two prominent anti-vaccine activists, scientist James Lyons-Weiler and Oregon pediatrician Paul Thomas, whose license would be suspended the same year — in part for his failure to adequately vaccinate patients — and then voluntarily relinquished two years later.

Comparing health outcomes of Thomas’ patients, the study concluded that unvaccinated children in his practice were healthier than vaccinated ones. It was retracted a year later following an investigation that “raised several methodological issues and confirmed that the conclusions were not supported by strong scientific data.”

Kennedy, like Thomas and other vaccine skeptics, has roundly rejected the body of scientific studies that show childhood vaccines are safe. Instead, he has embraced the unscientific theory that some ingredient or mechanism in childhood vaccines must be the culprit for chronic illnesses and conditions in children, from allergies to autism.

Kennedy published a book on the topic in 2023, “Vax-Unvax: Let the Science Speak,” in which he argues that vaccinated children are less healthy than unvaccinated ones, relying on studies, like the 2020 one, that have been criticized by scientists as methodologically flawed or in some cases retracted.

More on Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and vaccines

- More than 15,000 doctors sign letter urging Senate to reject RFK Jr. as health secretary

- Leaders of the anti-vaccine movement are thrilled RFK Jr. could run HHS: ‘A dream come true’

- RFK Jr. as Trump’s health secretary? Here’s what he wants to do

- RFK Jr. is courting Black voters, a group he once targeted with vaccine disinformation

- How the anti-vaccine movement is downplaying the danger of measles

It’s not clear how Graven, who died in 2022, became acquainted with Children’s Health Defense, or why he left after only a year. He was not against vaccines, according to his widow, his brother and a colleague interviewed by NBC News. His brother, Kendall Graven, who is also a doctor, said Graven hoped to teach Kennedy about how data is often misinterpreted by anti-vaccine supporters. Kennedy “was only mildly open to the concept of safe vaccines, in spite of Mike’s efforts,” Kendall Graven said, adding that “the Samoa catastrophe was nothing he discussed with us, other than to say it was a vaccine-preventable tragedy.”

Children’s Health Defense didn’t ultimately build a health information system for Samoa. Former Prime Minister Malielegaoi said he had not been swayed by Kennedy’s visit. “I was not interested in his ideas — he was not a medical doctor,” he told NBC News. “Our medical experts are more credible to me.”

Mary Holland, the president of Children’s Health Defense, declined an interview request. She replied to a list of questions with a link to an article disputing news reports that blamed Kennedy for Samoa’s low vaccine coverage.

Tamasese declined to be interviewed for this article, saying in a Facebook post that NBC News would “obviously twist whatever I say to try to prevent RFKj heading NIH in the US.” In a Facebook direct message, Tamasese said that Naseri had declined Children’s Health Defense’s offer of a data system. Naseri said he doesn’t remember such a proposal.

“I think there was some institutional resistance,” Kennedy told the Samoa Observer in 2021. “The measles epidemic occurred and kind of everything shut down in Samoa.”

The first case of measles was reported in September 2019, likely brought by a passenger on a flight from Auckland, New Zealand, to the Samoan island of Upolu. In October, it was officially an outbreak, and by November a national state of emergency. Samoa closed its schools, banned children from public spaces and made it illegal to discourage or prevent people from getting vaccinated. Red flags outside homes indicated there were children inside who needed to be vaccinated. Samoan officials said unvaccinated children were accounting for most of the deaths.

On Nov. 19, as the deaths neared 20, Kennedy wrote a letter to Malielegaoi, baselessly suggesting that the crisis was caused not by low vaccination rates but by a hodgepodge of possibilities, including ineffective or defective vaccines and newly vaccinated children “shedding” the virus to unvaccinated ones.

When Samoan officials seemingly ignored his letter, Kennedy reiterated the claims publicly on Facebook, according to a screenshot posted by an Australian anti-vaccine group, and called the government’s response “suspicious.”

Meanwhile, hospitals were filling up. In December, with dozens of children now dead, Samoa launched a massive vaccine campaign and passed a law mandating vaccines for schoolchildren. Global health organizations and countries near and far sent workers and aid. The World Health Organization bought Facebook ads encouraging vaccination in the Pacific region. New Zealanders sent child-sized coffins to help with the demand.

Around that time, Tamasese says, Kennedy reappeared.

Kennedy called him, Tamasese recounted in a video posted to an Australian anti-vaccine activist’s Instagram in 2023. “He said: ‘What’s going on in Samoa? Why are the kids dying?’”

Tamasese gave Kennedy his take: Children weren’t dying from measles but from the medical treatment they were receiving. He said Kennedy offered help.

“He put a team of doctors together,” Tamasese said of Kennedy. “Five doctors and scientists who were part of this team, and they were working with me. So it was like they were the doctors doing the monitoring and the prescribing, and all I was doing was going out and reporting back.”

Tamasese said he believed the measles outbreak could be treated with the same vitamins — A and C — that he had relied on to treat most other illnesses, and he felt compelled to intervene when parents of sick children started asking him for help. Tamasese said members of Kennedy’s assembled team — including Thomas, the Oregon pediatrician, and Jim Meehan, an anti-vaccine physician from Oklahoma and a speaker at Children’s Health Defense events — advised him remotely on a vitamin treatment: 1,000 mg of vitamin C in a fourth of a cup of water every 3 hours. “This will save your kids,” Tamasese said, posting the protocol on Facebook.

In 2022, recounting the same story in a comment on Substack, Tamasese said that one of the doctors on Kennedy’s team asked him to get a vial of the vaccine so he could analyze it back in the U.S., but that he had failed to do so. “The security around the vaccines was quite tight with each vial,” he said.

Thomas did not respond to interview requests. Meehan died in 2024. Tamasese began treating the island’s children, and at one point, at the behest of their parents, administered the vitamins to several who had been admitted to the hospital, he said. On Facebook, Tamasese claimed the children he treated were “surviving and thriving.”

“Yet our ministry continues to kill,” he wrote on Facebook. “When are they going to wake up? How many more need to die?”

Anti-vaccine activists in Australia and the U.S. were calling Tamasese a hero and organized vitamin drives so he could treat more children. At the same time, Samoan officials were begging anti-vaxxers to stay out of the way. Tamasese was arrested in December for incitement against a government order.

“We’ve had children who have passed away after coming to the hospital as a last resort and then we find out the anti-vaccine message has got to their families and that’s why they’ve kept these kids at home,” the government’s communications minister, Afamasaga Rico Tupai, told the BBC.

A photo of Tamasese in the back of a police car after his arrest went viral on American anti-vaccine pages, shared with a #FreeEdwin hashtag. He was released a few days later, with the conditions that he stop posting about the outbreak, surrender his travel documents and report to police once a week.

Six weeks after its mandatory door-to-door vaccination campaign began, 95% of Samoa’s children were vaccinated. School reopened and international emergency medical teams left.

Samoan officials recorded the final measles-related death in January 2020. Charges against Tamasese were dropped that year for lack of evidence.

And Kennedy would shift his focus to a different looming threat, the pandemic. His response to Samoa’s outbreak foreshadowed his approach to Covid-19 in the U.S. — one marked by misinformation, the undermining of vaccines, and the promotion of conspiracy theories and unproven alternative treatments.

Kennedy has never acknowledged the damage measles caused in Samoa and continues to promote conspiracy theories about the lives lost. “Nobody died in Samoa from measles,” he told an interviewer in August. “They were dying from a bad vaccine.”

The subject will no doubt come up during Kennedy’s confirmation hearings before the Senate Finance Committee next Wednesday and Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee next Thursday. Kennedy has spent weeks meeting with senators in preparation for the hearings, and many of them have reportedly been swayed by his claims that he’s not trying to take away vaccines but study their safety.

“He told me he is not anti-vaccine,” Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, told reporters this month. “He’s pro-vaccine safety, which strikes me as a rational position to take.”