This article was produced in partnership with Sky News.

OKLAHOMA CITY — Anthony Crawford worries his job may be in jeopardy.

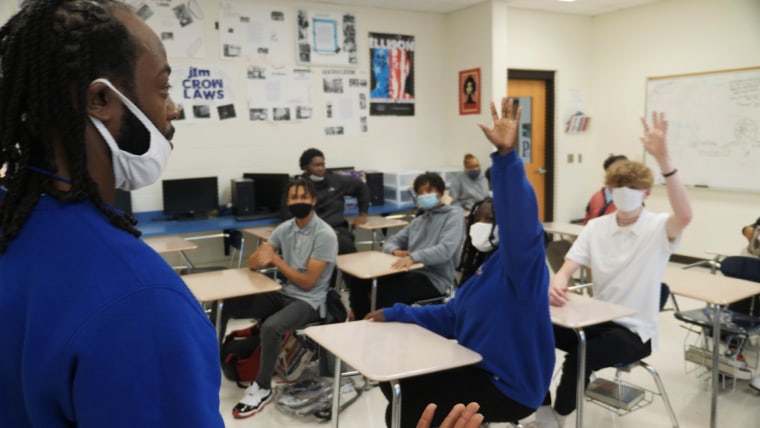

For two years he’s taught English and creative writing at Millwood High School in Oklahoma City, and since the murder of George Floyd, he’s held intense debates about race and history with his students. But a new state law, passed in early May, is set to ban the teaching of certain topics pertaining to systemic racism and implicit bias. The law doesn’t lay out clear consequences for violating it, but Crawford and several of his colleagues said they expect the legislation will have a chilling effect on teachers.

“It has to, because now for teachers, you don't want to lose a job,” said Crawford, 31, who is Black. “I don't want to talk about this knowing that it could be possibly a lawsuit or a possible way for me to lose my job.”

Oklahoma’s new law targets critical race theory, a study of the legacy of racism and its history in legal and social systems. It was developed by Black scholars more than four decades ago to provide a framework for understanding how laws and practices have perpetuated inequality.

But a growing chorus of conservatives use the phrase to describe a range of diversity and inclusion training and teachings about the pervasiveness of racism that they argue are divisive and likely to make students — particularly those who are white — feel guilt and anguish.

Rep. Kevin West, a Republican and one of the authors of Oklahoma’s legislation, did not put the words “critical race theory” in the bill, but he acknowledges that is what’s in its crosshairs. “It’s that overall concept,” he said. “Critical race theory is more like just an umbrella statement.”

Fights over how to talk about racism in schools have boiled over in communities from Texas to Utah and California. Oklahoma is one of at least a dozen states that have introduced measures to ban or limit teaching about systemic racism, bias and privilege in schools.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, one of the founders of critical race theory and a professor of law at UCLA and Columbia Unversity, sees these laws as a backlash to the racial reckoning of last summer, when Floyd’s murder sparked uncomfortable conversations about diversity, inclusion and history in many workplaces, schools and universities. She doubts most of her critics have ever read her work: “It's like a bad case of telephone,” she said. “It's a catchall for everything that people don't want their children to learn. And that's why it's been so successful. People don't know what it is. But now there's a name for that thing that goes creak in the night.”

Jenni White, a mother of five in Luther, Oklahoma, who advocated for the state’s new law, describes feeling like a “pendulum has swung” in America since her upbringing in the 1960s. She believes the civil rights movement was necessary to reverse “horrifying” racism against Black people, but the conversations she says she has observed over Zoom in some school districts alarm her.

“I've seen things that are coming out of schools where I'm supposed to apologize for my whiteness,” she said. ”You’re going toward, you know, demonizing a population just like we demonized another population.”

Teresa Manning, a former Trump administration official and now the policy director of the National Association of Scholars, a conservative education advocacy organization, also opposes discussions of marginalization and bias in schools. She emphasized that teachers in all of the states where similar bills are passed will still be able to talk about historical events like slavery in context, and described the laws as a defensive measure against “psychological warfare” from those who hate America. “It's a defense of the country, of Western principles, of individual rights, a defense of the ideals of America,” she said.

Sapphira Lloyd, a 16-year-old in Crawford’s class in Oklahoma City, believes the law is focused on assuaging the discomfort of white students at the expense of Black students like her.

“Does anyone care about the comfortability of Black people? Obviously they don’t care,” she said. She and other classmates noted that nobody in Oklahoma thought to legislate to prevent Black students from hearing traumatic stories about slavery or racial violence. In her view, the law will make quality history instruction impossible. “You cannot talk about American history without speaking about racism. You cannot do it.”

Oklahoma’s new law will go into effect before the next school year. At Millwood High School, Superintendent Cecilia Robinson-Woods heard from teachers like Crawford who want to know whether the district will support them in teaching race and history as they always have. While the law doesn’t describe specific punishments, she has reassured the teachers that she expects challenging discussions of racism and inequality will continue, whether state lawmakers approve of them or not.

“The world is changing,” she said. “We can't stop it. No law is going to stop that.”