ISTANBUL — It has been three months since Mehmet Demir’s home was reduced to rubble by two massive earthquakes that devastated huge swaths of Turkey, killing tens of thousands of people and displacing almost 3 million.

And like many of his compatriots, he doubts whether his country’s leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, can survive the aftershock in Sunday’s presidential election.

Erdoğan, whose grip on power long looked unassailable as he flexed the country’s muscles within Turkey and beyond its borders, now faces the biggest threat to his premiership. A languishing economy, earthquake-ravaged regions and a backlash against millions of Syrian refugees are among the issues that could end with his ouster.

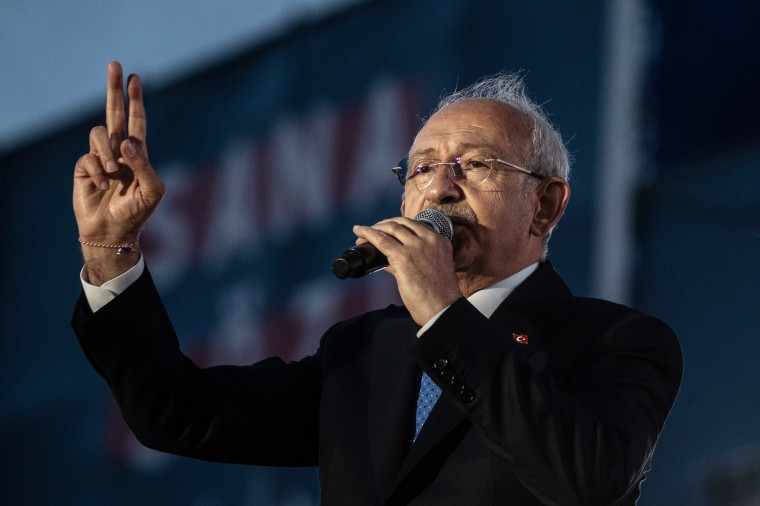

The hotly contested election pits him against Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the joint candidate of an alliance of opposition parties, and Sinan Oğan, who is running as an independent. To win outright, a candidate needs 50% of the vote, but if no one crosses that mark, a runoff will be held May 28.

Voters will also elect 600 members of the Parliament, known as the Grand National Assembly.

With or without Erdoğan, “I am not seeing any future for this country,” Demir, 52, said Wednesday by telephone from his home in the southern city of Hatay.

Demir, a shopkeeper, said he lost hope in the state after he had to retrieve his wife’s body on his own from the rubble of the five-story apartment building, 48 hours after the quakes struck.

“My wife could have been rescued if the emergency workers were present at the site on time,” he said, adding that they arrived after three days, when it was too late.

Now living near their old home with his two teenage daughters in a container city — consisting of prefabricated housing units resembling shipping containers — Demir said he would not be voting for Erdoğan despite his apology for the government’s slow response after the earthquakes and his promise to build hundreds of thousands of new homes in the most affected areas.

Elsewhere, Ferdi Baran, whose apartment building in Hatay was reduced to rubble in seconds, said he felt “distant” from all the candidates but was veering toward Erdoğan.

“I feel offended at the government because they couldn’t efficiently intervene in the aftermath of the earthquake,” said Baran, 40, a furniture maker who is living with his wife, Sevsem, and two children in a tent city near their old home.

He also said he felt offended by the opposition, who “didn’t really do anything except making propaganda against the government.”

But he said Erdoğan and his governing AK Party might be able to repair and rebuild areas affected by the earthquakes more quickly than a coalition of governing parties.

Outside Turkey, the result will be watched with interest. The opposition alliance has signaled it would seek to rebuild ties with the U.S., the European Union and NATO. Erdoğan’s government has blocked Sweden’s accession into NATO, so if he were to lose, that veto might end.

Inside the country, Erdoğan will most likely have the backing of Turkey’s Syrian population, which numbers 3.7 million, making it the world’s largest refugee community.

Syrian refugees were once welcomed as they fled their country’s civil war — now in its 12th year — but calls for them to return home have been revived amid a shortage of housing and shelters after the earthquake.

Both candidates running against Erdoğan have promised to send them back. Oğan, who is backed by an anti-migrant party, has said he would use “force if necessary,” while Kılıçdaroğlu has said he would repatriate them on a voluntary basis.

Erdoğan has barely mentioned the migration issue on the campaign trail. But faced with a wave of backlash against refugees, his government has been seeking ways to resettle Syrians.

Nasir Muhammad said he didn’t “want to think about what would happen” if Erdoğan lost, because although he gained Turkish citizenship six years ago, some people still consider him a Syrian refugee.

“My Turkish neighbor told me that I had to pack my bags and prepare myself to leave if Erdoğan loses the election,” Muhammad, 51, said Thursday at the barbershop he founded in the southern city of Mersin.

Marwan al-Hassan, who opened a car dealership in Istanbul after the earthquakes destroyed his home and business in Hatay, said he couldn’t return to Syria “because my life and the lives of my children are in danger there.” Hassan, 45, said President Bashar al-Assad’s regime would kill him if he went back. If worse comes to worst, he said, he would try to go to Europe.

While there has been “a rising nationalist, anti-immigrant wave strong across the board,” for Karabekir Akkoyunlu, a lecturer in Middle Eastern politics at SOAS University of London, the economy in Turkey, where inflation soared above 85% last year, is “the single most important reason Erdoğan faces potential defeat in the polls.”

“Turkey has been in an economic crisis since 2018,” he said, adding that the inflation rates had “hit households across the board.”

Most of Erdoğan’s base, he said, “appears convinced that his government is not to blame for the tens of thousands of lives lost.”

“They either buy the official argument that this was a catastrophe of biblical proportions which no government could do anything about, or they blame smaller actors, like contractors, ignoring the political system that made extensive corruption and nepotism possible,” he said.

He added, however, that “the actual impact on the polls will also depend on whether the earthquake survivors will be able to vote, given that many of them have been displaced.”

Only 133,000 people across the entire country have reregistered at new addresses outside their homes, according to Turkey’s Supreme Election Council. The International Organization for Migration said in March that almost 3 million people had been displaced after the earthquakes.

That means many will have to travel to vote, like businessman Ali Catal, 51, and his family, who will make the 650-mile journey from İzmir back to their former home in Hatay to vote.

“These elections are very important to us, not only for us, but for everyone living in this country,” he said.

Neyran Elden reported from Istanbul and Ammar Cheikh Omar from Mersin.